“New Geographies of Feminist Art: China, Asia+the World: A Symposium” at the University of Washington gave us an opportunity to think about feminism today and how it can be redefined by new realities. The feminist movement in the US re-emerged in the late 1960s and 1970s as a part of the many resistance movements of those years that built on the Civil Rights legislations of the 1950s and 1960s. Some of the primary campaigns were on equal pay and equal access to health care and birth control (issues that are still with us). In the art world, misogyny, racism, and elitism, became a focus. Looking back at that art (as we could do this fall in Seattle in the “Elles” exhibition), we see women asserting themselves mainly with their bodies: Hanne Wilke amusingly undresses in front of Duchamp’s “Bride Stripped Bare By her Bachelors Even.” But elite and beautiful female artists undressing seems dated and pointless today. ( Wilke’s later work as she was dying of breast cancer is more resonant today)

Issues for women’s bodies, such as-again with reference to the Elles exhibition-Tania Brughuera’s painful manipulation of her mouth as a metaphor of the difficulties of speaking out–point more directly to present concerns.

Today women artists are reaching out beyond “art world” issues, and “body” issues, to address what is actually happening in terms of our planet and its people. Feminism in art today is embedded in cultural and geographical differences.

That is the premise of the conference “New Geographies of Feminist Art: China Asia+the World” organized collaboratively by Art Historian Sonal Khullar and Sasha Welland, Gender, Women and Sexuality Studies Professor. The symposium offered an impressive array of brilliant, predominately young, Asian, female scholars and curators, as well as three well-known artists, Navjot (who came from Mumbai), Wu Mali based in Taiwan, and Hung Liu, formerly of China, now in California, and a professor at Mills College.

The keynote address was given by Shu-mei Shih, Professor of Asian Languages and Cultures, Comparative Literature and Asian American Studies, at UCLA. Her main theme was “interconnectiveness” – “minor” sites are as important as “major” sites. She declared that feminism was an “ethical position” rather than simply a depiction of victim hood.

As examples she talked about several performance artists who address feminism as an action, and a method, but not as content. In other words, art about the female body is being replaced by metaphors that have a broader significance.

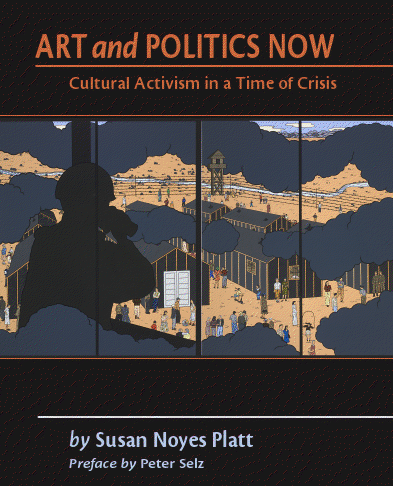

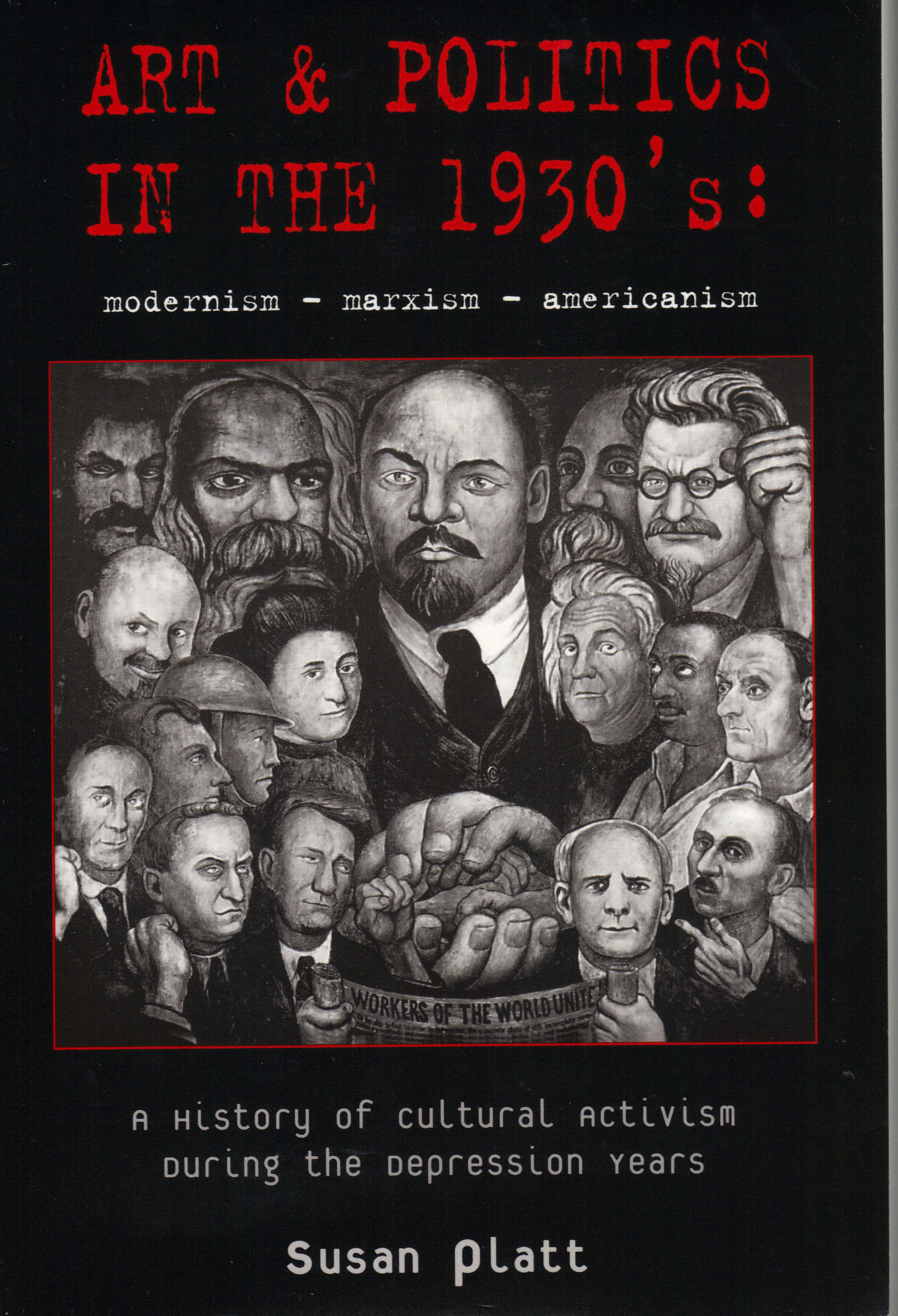

The clearest example was the work of Wu Mali. While her earlier work is specifically about women’s stories and aesthetics, of which a wonderful example, Secret Garden, was featured on the symposium website,( see above) and her current work is a community-based practice addressing environmental issues ( second image above). she declares that

“Despite the various subjects, I am really dealing with only one core issue in my works: how does a person exist comfortably in an environment? Although a straight-forward question, this has never been a simple affair. For example, coming from a gender perspective one faces gender issues, in urban development one encounters class issues and the relationships between a nation’s power and its citizens. These matters are entangled with many complicated issues, but all derive from the question of how does one go about settling in his or her environment? How does a person live happily in despite of one’s identity, gender, background, or social class? If you look at things from these perspectives you’ll find many problems; when a person faces their surrounding, it is a land issue as well as an institutional issue.”

Another artist who was featured at the symposium, Navjot, moves easily between the realms of abstract theory and concrete collaborations with indigenous people and street children. Her position is that “the artist does not solve problems, only raises questions.” One question she raised was “why do people migrate,” as she observed how impoverished life was in the shanty towns of the city compared to village life. Navjot, like Wu Mali, has many strategies and themes in her work, and she collaborates with artists and the general public.

She is deeply concerned about ecological issues such as water pollution and the privatization of water. Her concern is to encourage creative thinking rather than to follow a preordained idea. She believes that something as simple as providing children with a place to play is a step toward a future society that is not wracked by violence. She also works with the public in urban areas, a much more unusual practice in India than in the United States.

Sonal Khullar, one of the symposium organizers, in her all-to-brief introductory remarks, spoke of migration and incarceration in relationship to historical violence (giving the example of Mona Hatoum’s potent work Traffic two suitcases connected with hair). This is a theme that I am really interested in and I wished she had spoken more about it.

But she rapidly moved onto another question. How does contemporary art disrupt predictable connections- with the example of Rina Banarjee who irreverently placed her large sculptures based on an outrageous contemporary kitsch aesthetic into the somber Musée Guimet in Paris.

A third theme was historical figures who embody transnational feminism, with the example of Amitra Sher-Gil, an early modernist and transnational elite, who studied art in Paris, then returned to India.

Sasha Welland, the other organizer, explained that the symposium was one response to the feminist shows “WACK! Art and the Feminist Revolution” and “Global Feminisms, New Directions in Contemporary Art” The second show actually had two catalog essays on Asian feminism, but only about ten out of the eighty artists came from Asia. Welland emphasized relations across difference, transnational gender, race, class and nationality as a basis for feminism, not politics specifically about women. Examples she gave were Lei Yan, “What if the Long March Had Been a Women’s Rights March?”

She also sited Chen Quilin, whose home and village were in the path of the 3 Gorges Dam. This young artist creates theatrical short films in urban settings that suggest the disjunctions of the great loss caused by the dam.

One crucial group of speakers established that feminism has deep roots in China and India, and that it allies with the nationalist discourse of the mid twentieth century. This is not at all surprising, given that modernism throughout the world allies with secularism and women’s rights among elites. In fact, it is that alliance that has been progressively undermined in the last twenty years by the rise of reactionary Islamist male political leaders. China, of course, is a special case, with the victory of Communist ideology. Communism promoted women’s equality in some ways, as well as equal opportunity deprivation and oppression.

The artist Hung Liu, the final speaker, who grew up during the Cultural Revolution in China,told the mythical story of “Nuwa and Her Descendents” (also a television series in China). According to the myth, Nuwa is the Creation deity and she made humans with clay. There are several other dramatic chapters to the story such as “Ancient ancestors offended the deities and the God of the Heaven punished them by creating disastrous floods” (hmm perhaps that is what is happening today) Hung Liu’s retelling of the tale of this powerful deity followed by a specific discussion of some of the personal experiences underlying her own work, was a dramatic conclusion to the symposium.

It is impossible to do justice to all the topics and artists addressed in this brief analysis.The symposium as a whole was provocative and exciting, but I left with many questions.

First, the title “China, Asia +the World” made no sense to me. Is not China in Asia, and where is India in the title and what about naming other parts of Asia? I need to ask the organizers about this, as it was obviously carefully thought out.

Second, exactly in what ways is ecological art the new feminism? That was the theme, based on the “geographies” of the title, and established in the keynote speech, but not sufficiently pursued Simryn Gill, Geographer, for example, (her work is at the top of the post)was thet title of one talk, but it was difficult to see how her work is feminist.

Wu Mali was the most specific example, with her transition from women’s issues to community based art, but as the overarching thesis of the entire symposium, it needed more development. Also, there is some risk in this idea of vague generalities., rather than pointed content that exposes injustice. I am not advocating a focus on “victimhood” as Shu-Mei Shih termed it, but many women artists today have strong voices concerning specific issues.

Nalini Malini’s is one of them- there was a presentation on her which I missed. There are many more.

Third, there were a lot of presentations on China. I would have liked to have seen more discussion of other parts of Asia, more geographies.

For example, it is an urgent feminist issue and a new geography that young girls are trafficked from Nepal across the Indian border every day. Or in India and elsewhere, the abuse of young brides by their in-laws continues and their only way out is often self-immolation. Nilima Sheikh addressed the second topic some years ago in her Champa series from the 1980s.

Sheikh also addressed women caught up in the Partition based on the book by Urvashi Butalia, The Other Side of Silence, voices from the partition of India. She was mentioned all too briefly in the symposium.

There is a certainly a strong relationship between women, place, and aesthetic in contemporary feminist art. There are infinite possibilities for 21st century feminist artists to address issues on the ground. Many are already doing that. I hope that these brilliant scholars keep their eyes on those artists as they further develop their work on the new geographies of contemporary feminist art.