“Our America” Abstraction and Identity

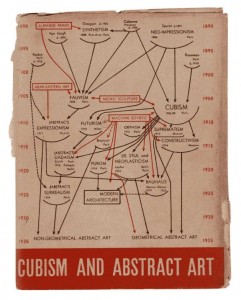

In 1988 I published an article in Art Journal with the title “Modernism, Formalism, and Politics: ‘The 1936 Cubism and Abstract Art’ Exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art.” You can read it here. In my article I demonstrated the way in which Alfred Barr, in the midst of Hitler’s active destruction of modern art which he personally witnessed in the early 1930s, sought to save modern art by enshrining its history outside of history, as a history of abstract forms. Although in the 1920s Barr embraced “Neue Sachlichkeit” ( new realism, with artists like Otto Dix), Dada, Surrealism and various other directions, in the 1930s Barr basically invented the idea that pure abstraction was the main goal of artists in the early twentieth century. He traced its emergence descending from post impressionism in two branches, one through Cubism, Suprematism, de Stjil, and Constructivism; the other through what he described as (abstract) expressionism, (abstract)dada, and (abstract)surrealism.

This “evolution” was first presented in a complex diagram, familiar to all of us, in which Alfred Barr acknowledged other reference points in red boxes ( Near Eastern Art, African Art, Machine Art) but his flow led inexorably to what he called in 1936 “geometrical” and “non geometrical” abstract artists.

Barr arbitrarily established the centrality of abstraction in this hugely influential exhibition and catalog. After World War II, formal analysis and abstraction as a superior (democratic!) force and expression of “freedom,” exploded with the influential support of Clement Greenberg, the CIA, and the Communist witch hunts of the McCarthy era which led artists to avoid politics and even any imagery at all.

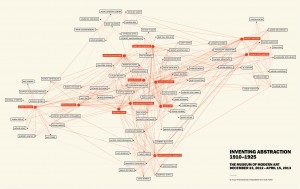

The 2010 exhibition “Inventing Abstraction 1910 – 1925” at the Museum of Modern Art re-enshrined abstraction as the ultimate event in early modernism and included a new interactive chart. By not including any references outside of the artists interrelationships, it was actually even more insular than Barr’s.

Criticism of the exhibition pointed out that this was “white European abstraction” and that abstraction existed all over the world. That is a crucial opening for more discussion of what abstraction means, how many different types of art it encompasses, and, above all, how many different interpretations it offers. The term itself tends to stop us, much as the 2010 exhibition did, our brains turn off, and we see abstraction as a monolithic position in European/US culture.

Of course, early twentieth century modern art in Europe and the U.S. as a whole, with abstraction as one aspect of it, has been of great significance in Latin American modernism, among cultural elites. (See my review of the exhibition at the Museo del Barrio) Latin American modernism of the twentieth century has a distinct character, beginning in the 1920s with the work of the Uruguayan Joaquín Torres-Garcia

Joaquín Torres-Garcia

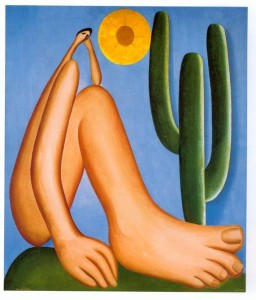

and the Brazilian Tarsila do Amaral, the central figure in a major movement with a manifesto, “Anthrópafago.”

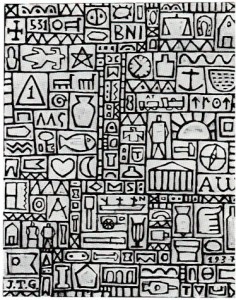

Torres-Garcia’s work bring together Constructivism with a private vocabulary of symbols. Tarsila transformed a modern style learned in Paris, especially from Leger, with imagery based in indigenous and Brazilian popular art references as well as surrealism. But neither Torres-Garcia nor Tarsila are purely abstract artists relying only on shape, color, etc. Their art is layered with context and multiple geographies, texts, references, and personal perspectives.

So now let us turn to the abstract art in “Our America.” Each of the artists included has a different trajectory, perspective, context, country of origin, class, life experience. Together they underscore the complexity of what abstraction means. Some critics have suggested that artists of color are denying their identity by turning to abstraction; actually we see here that the artists are embracing who they are as they alter the parameters of abstract art.

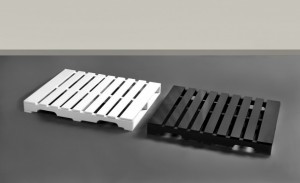

Jesse Amado, Me,We 1999,granite and marble Gift of Henry R. Muñoz III in honor of Lyman Morgan Jones V© 1999, Jesse Amado

Me/We by Jesse Amado on first glance appears to be a minimalist sculpture, geometric, stone, impersonal. But on closer examination, it is clearly an exact replica of wooden shipping palettes. The two halves of black granite and white marble sit adjacent close to the floor, but do not touch. We tower over the sculpture, forced to look down. The work honors workers who lift these palettes not only in its form, but also in its title. “Me,We” is a two word poem that Muhammad Ali read at Harvard when he was given an honorary doctorate. (exhibition catalog. p. 95) In just these two words, Ali, and now Amado, speak of our connection to society, our shared world. through these spare expressions.

Ruben Trejo Mandalas1986-1990 welded iron railroad spikes, marble, iron sheet, lead, and wood Gift of the estate of Ruben Trejo

Mandalas by Ruben Trejo is another transformation: in this case actual railroad spikes welded together to form two lines hanging down, and one standing upright that recalls, except for its slight sway, Brancusi’s Endless Column. The sense of gravity shaping the work, and acting on it, is subtle and crucial. With his title, Trejo sanctifies the material of his father’s humble work hammering railroad spikes. These spikes not only have an energy of their own, they seem about to break loose. This sculpture is not simply to be looked at, it is to be experienced viscerally: it gives us contradictory sensations and feelings, much as the artist himself must have had coming from humble beginnings (he was actually born in a box car) to the making and teaching of sculpture in a small town in Eastern Washington State isolated from his Mexican roots. (exhibition catalog p. 323)

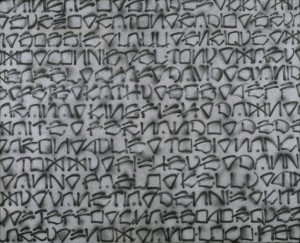

Charles ‘Chaz” Bojórquez follows an entirely different trajectory. He began as a graffiti artist in LA, but his large oil paintings, with repeated undecipherable writing, appear to be a private language, a work of esoteric conceptual art. Those two widely separated worlds come together in this work, Placa/Rollcall . The idea of graffiti marking territory for gangs here metamorphoses into a painting

Charles “Chaz” Bojórquez, Placa/Rollcall 1980 acrylic on canvas

Gift of the artist

using a personal calligraphy that the artist has developed based on his interest in old English letters and Asian calligraphy. Within the calligraphic shapes are names of people that he cares about, but only the initiated can read it. Again, for the mainstream viewer the work is abstract, for the urban street world of Bojorquez and his friends the work speaks of territory, friendship and pride. (exhibition catalog, p 111)

J

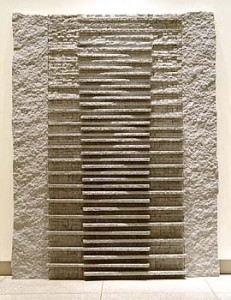

Jesús Moroles granite wall of stone Granite Weaving has the presence of a Mayan or Aztec pyramid. We see both the material and a sense of history in the work as soon as we stand in front of it. Moroles was an assistant to Luis Jimenez, an experience that led him to large scale sculpture, but in the opposite material and aesthetic from Jimenez. While Jimenez works in fiberglass and directly evokes both his own presence and historical references in his Man on Fire, for example, Moroles works in the stone of the earth, the stone of permanence, of ancient art and architecture. He has a personal relationship to the stone, saying “The stone speaks to me and I speak back.” (exhibition catalog, p 259) which recalls Michelangelo’s relationship to marble. Yet, Moroles’s works evoke ancient forms, (another is a stele,) or ancient cultures, that achieved monumental permanence in Mesoamerica, Egypt, and Asia. He is not culturally specific, or historically limited. Moroles monumental modernism has within its abstract forms the possiblity of experiencing history as a continuum to the present moment.

Turning to other painters in the gallery, we have in addition to Freddy Rodriguez, discussed in the previous blog, Carmen Herrera and Olga Albizu. In the case of painting, the risk of comparison to known white men is greater. Departure from the canonical techniques and forms means that the artist doesn’t “get it.” But if the art is absolutely contemporary with the current styles, and simply by a lesser known Latino/a artist, then it is “derivative.” These phrases seem to attach onto painting more quickly than to sculpture.

Carmen Herrera Blanco y Verde 1960 Museum purchase through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment 1960

Carmen Herrera was a woman who moved comfortably between Havana, Paris and New York. She is older than the generation of Cubans who emigrated to the US following Castro’s revolution in 1959. She was part of an international community of artists from many countries who came together mainly in Paris and New York City, as a modernist avant garde in the middle twentieth century. Her formation coincided with post World War II French artists pursuing a hard edge abstraction that they called “réalités nouvelles” [new realities], so in that she is continuous with Torres-Garcia in his 1920s affiliation with hard edge Constructivism.

Blanco y Verde was painted in 1960 at the height of abstract modernism in New York City. Herrera has a cool palette, and a hard edged form, but at the same time, her work is unlike other artists of that time, it sets us off balance, and suggests that we cannot quite dismiss everything that seems to have been taken out of the art. Herrera speaks of rejecting the spiritual, the mythological, the religious, and in this cool work, she presents the rational. But, actually, with its off kilter relationships it still invites the sense of uncertainty that is the opposite of the rational. It is also extremely elegant, echoing the artist’s personal style. One has to ask, is hard edged abstraction an elite practice, possible only with the most fortunate? Or is it a tenuous place, a balancing act that can lead into the abyss at a moment’s notice?

Herrera did not start selling work until she was 89 years old, but is currently regarded as a hot, contemporary artist. Just goes to show, if you live long enough, anything can happen! Her success also underscores the continuing love of abstract art in contemporary art.

And finally, but by no means all of the artists in this gallery of abstraction, is Olga Albizu’s Radiante, 1967. Albizu studied with Esteban Vicente at the University of Puerto Rico, an artist who later went to NYC, and was part of the early abstract expressionist movement. Albizu also came to NYC and studied with Hans Hofmann. Radiante is on the poster for the exhibition which brings us back to Curator Ramos’s intention to demonstrate that Latino artists participated in all the major styles of the late twentieth century: Albizu’s Radiante is an abstract painting with the colors of the Caribbean; it has highly saturated and particular yellows, oranges and blacks against a yellow field, applied with a thick palette knife.

Her work was featured in 1964 on the cover of a Stan Getz/ João Gilberto’s jazz album, one of the best selling bossa nova albums of all time, since it featured “The Girl from Ipanema.”(exhibition catalog p. 89) Albizu’s work is contemporary with the height of abstract expressionism, but she did not, as a young woman from Puerto Rico, hang out with those famous alcoholics at the Cedar Bar. There is a controlled and subtle sensuality to her work, that speaks of hidden layers of emotion, rather than letting everything appear on the surface to be consumed. In the case of Albizu, the connection to music, and particularly Bossa Nova, as well as her exposure to Hans Hofmann’s ideas of “push and pull,” allows for the work to exist without other reference points. The colors do indeed move like large full sounds, a connection that takes us all the back to Kandinsky.

So, clearly, Alfred Barr’s deterministic evolution toward abstraction continues to be influential to the present moment. But, a more accurate representation of modern art would be an inclusive, complex story, with roots and branches for each artist according to their own experience. The fact that “Our America” has such a large gallery of abstract works does, however, reflect the importance this practice has been given in the history of art. It is, irrefutably, still perceived as the mainstream, and it is against a monolithic concept of abstraction that so many other artists have reacted.

Note: the catalog for the exhibition Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art by E. Carmen Ramos, with an introduction by Tomás Ybarra-Frausto (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C., 2013) cited at several points in this review, is invaluable. It can be purchased from the Smithsonian Museum of American Art.

This entry was posted on March 10, 2014 and is filed under Art and Politics Now, art criticism, Contemporary Art, Latino Art, Uncategorized.