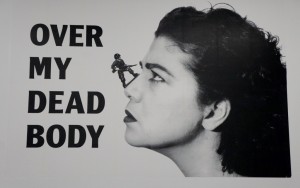

While this early poster/billboard by Mona Hatoum might seem amusing at first, it is actually deadly serious and not a pun.

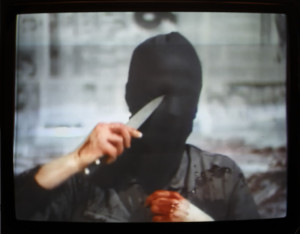

Mona Hatoum confronts us directly with the nightmare of violence in her early performance work. Here is a description of Variations on Discord and Divisions (1984) “. . . the artist, wearing an opaque mask and all dressed in black, crawls between the rows of spectators to reach the performance space. She then performs a number of actions that culminate with her removing raw kidneys from under her clothes, cutting them up, putting them on plates, and serving them one by one to the audience.” (“A Prologue to the Past and Present State of Things

Variation on Discord and Divisions: Mona Hatoum, Ibraaz,

009_00 / 2 July 2015)

Below is a still from that performance of the early 1980s. It could have been made yesterday. It captures the horror of unexplainable violence. We in the West like to say that only Islamist (ie politically motivated and brainwashed) terrorists commit the kind of barbaric acts suggested by this image, but of course it is all of us. (The recently approved US budget for combat operations alone was 40 billion). Anonymouos drone attackes and ongoing murders of black people by police in the US are only two examples.

Learning of the visceral intensity of Hatoum’s early work transformed my understanding of her art. It came through even in the documents of the 1980s performance pieces in the current exhibition at the Tate Modern. In them you see the artists’ highly compressed emotions of anger and frustration with the political situation in Palestine and the Middle East. As a Palestinian refugee in Beirut

(albeit a privileged one with a British passport), she felt deeply displaced when she was unable to return home from London on what was to have been a short trip because of the Civil War in Lebanon.

Live Work for the Black Room

Three works represented by photographs and notes are Live Work for the Black Room 1981, Under Siege, 1982 and The Negotiating Table 1983. In the first ( above) described by the artist as about “death, disaster, doom and gloom,” she falls to the floor repeatedly in a completely black room, drawing a chalk outline of her body, then places a candle next to it. The photograph has an odd abstract quality, although details show the outlined bodies clearly, as in a crime scene.

Under Siege

In Under Siege she stands inside a transparent cube covered in clay, then falls down repeatedly for seven hours.

The Negotiating Table

Repetitive falling changes to stasis in The Negotiating Table: the artist encased and immobilized by bloody entrails, her head covered in gauze, lies motionless on a table assuming the aura of a sacrificial animal. Empty chairs surround her: failed talks lead to dead people. All of these works have soundtracks of war news and leaders talking about peace.

In these same years, Hatoum also explored video art, but in an entirely different way from feminist video in the US. She immediately perceived the camera as a physically invasive force. During Don’t Smile You ‘re on Camera, 1980 she moves a camcorder across the bodies of individuals in a small audience, alternating those images with projections of naked bodies.

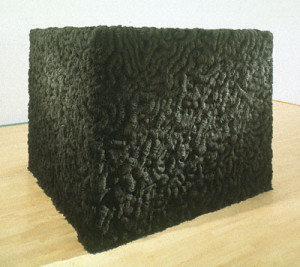

She continues this exploration of the body in literal depictions such as Socle du Monde 1992-3, a large cube with “intestines” covering its surface, evoked through iron shavings that curl convincingly as the tubes of our innards.

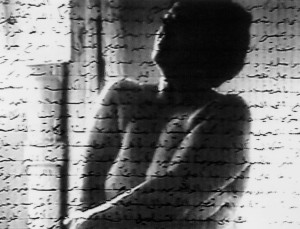

Measures of Distance, 1988, records her mother in the shower (shown behind a “curtain” of Arabic script that resembles barb wire). The artist reads letters from her mother as the text of the piece that address both her mother’s own deep sadness in exile, and her relationship with her daughter. One of Hatoum’s best known works, Corps Etranger 1994 takes the idea of photographic penetration much further by filming medical imaging footage penetrating her own body. We stand on top of the video as another invasive force as we watch it probe her inner body.

But in spite of her intense performances and intimate explorations,

only once in her entire career, in Measures of Distance, does Hatoum include personal details. Otherwise we only have the fixed, brief biography of her early years in Beirut and move to London. We know nothing else of her life.

Hatoum’s concern is to make the feelings of her art penetrate us. She does not want us to have an opportunity to tell a story, to narrate a context. She manages to convey the large atrocity of war, destruction, and exile, without any specifics at all. In that way, she rises above who she is, and who we are, and speaks of the human condition as we reap the emotional harvest of violence.

Undercurrent exemplifies her understated metaphors open to several interpretations: at the same time that it terminates its spiraling paths of red electric cord with light bulbs that suggest an ending, and a woven center that may suggest collective resistance, it can also be alluding to bleeding to death, electrocution and torture. Even as the poetry of the piece captures us, we are enmeshed in its multiple meanings.

That subtle ambiguity is obvious in Hatoum’s ongoing use of her own hair as a major material for her art, in entire installations of balls of her hair, or sewing with hair and most remarkably, weaving the particular pattern of the Keffieh with hair (which some writers explore from a feminist perspective). Those cast off dead cells, that fragile filament, becomes a layered statement about death, life, and their eerie balance. The delicacy of the works made of hair make them recede almost into invisibility, but that invisibility is the point.

In contrast to invisibility, another experience in Hatoum’s work is a sense of threat, entrapment, and anxiety. Through a barbed wire fence we view Home 1999, a table covered with ordinary kitchen appliances like colanders and cheese graters that serendipitously lights up and creates loud noises. The unpredictable threat to what should be the security of home is a theme the artist explored as early as 1979, and it has many iterations such as Homebound, 2000, shown at “Documenta” in 2002 which included a bed, crib, and chairs.

Sometimes we have just a huge grater as a room divider or a bed. These works have been compared to Martha Rosler’s famous Semiotics of the Kitchen of 1975. Rosler also transforms ordinary kitchen implements into threatening objects. But for Rosler, she holds the knife, she wields the threat, and for Hatoum the threat comes randomly from outside, beyond her control. Hatoum references the impact of war on individuals, while Rosler redefines and defies social expectations for women, a very different point of reference.

Sometimes we have just a huge grater as a room divider or a bed. These works have been compared to Martha Rosler’s famous Semiotics of the Kitchen of 1975. Rosler also transforms ordinary kitchen implements into threatening objects. But for Rosler, she holds the knife, she wields the threat, and for Hatoum the threat comes randomly from outside, beyond her control. Hatoum references the impact of war on individuals, while Rosler redefines and defies social expectations for women, a very different point of reference.

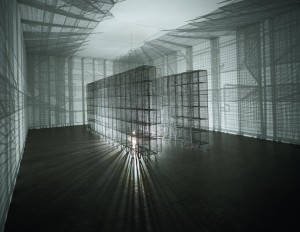

Deeply affecting in its simplicity, Light Sentence 1992, features a room with stacks of small cages arranged in two rows, some with their doors open, lighted by a single bulb that rises and falls between the rows. The magic of the piece and its contradiction is the shadows of the cages cast on the walls, constantly moving, mesmerizing abstract patterns. The shadows escape the entrapment of the cages. Poetry competes with claustrophobia.

Hot Spot, 2006, a grid/globe with red neon marking the continents joins her ongoing manipulations of maps, globes, and borders as in Map made from glass marbles on the floor, escaping their geography,

or the map of the world created by removal of fibers in a woven carpet, Bukhara (red and white).

As the marbles slip around the floor and the carpet conveys the absence or the globe’s glow spreads through a room, the concept of mapping and borders as an arbitrary source of conflict and war is obvious. And of course it all comes back to Israel /Palestine, the root of Hatoum’s own exile and that dreadful unsolvable conflict based on the colonial decisions of over one hundred years ago.

Present Tense, 2200 blocks of Palestinian olive oil soap and red beads marking the Oslo Peace Accord of 1993

The early performances provide the foundation for all that follows in Hatoum’s work.

While the artist’s body now appears only in its dead cells (hair, nails, blood), Hatoum expresses the same violence and compressed terror through the ordinary objects of everyday life and in our own lives. Hanging Garden as installed at the Tate, brings it home: bunkers that have stayed so long that they have grown grass. By looking at the metaphors latent in the objects she chooses from our daily life, we feel inside us the corruption of humanity in our intensely violent world.

Mona Hatoum looking through the barbed wire of her installation Impenetrable