On the second night of our cross country train trip, we passed through Minot, North Dakota. It was minus fifteen degrees. That is about two hundred miles north of Standing Rock and the ongoing resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL) still continuing in sub zero weather and blizzards. Now we have the escalation of tensions with the illegal orders coming from the White House. There is a renewed call to Activists to return to Standing Rock

Activism by artists is crucial to continue to highlight the situation.

Right before I left Seattle, I attended two exhibitions supporting the DAPL resistance. The resistance is encouraging a surge in contemporary native art and exhibitions supporting Standing Rock. In Seattle we also built eighty winter shelters known as “tarpees,” tepee-shaped but covered with heavy duty poly wrap and large enough to hold stoves with a long stove pipe going through the roof.

They were designed by Paul Che oke’ ten Wagner, the famous flutist who explained his name as “of a feeling to watch over, to care for the people and things that you love for many seasons.” Paul has been an inspiring and generous spiritual leader in Seattle at every DAPL march and demonstration. Now he is also an architect. He is combining contemporary materials and traditional structures to create an entirely new type of tepee.

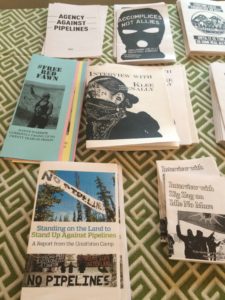

A fundraiser for the “water protectors,” at the new Sacred Hoop Cooperative Gallery at 55 Bell Street included ceramics, posters, beadwork, paintings, masks and graphic art. One whole table was filled with writings about Standing Rock, poetry, and graphic books that dramatically told the story of the conflicts of whites and natives over several centuries.

But primarily, the event was about story telling by those who had just returned from Standing Rock. It continued for eight hours!. While I was there, the story being told was both personal and mythic, the storyteller, a large man who declared he was like a bear, had just returned from Standing Rock. He told of the spirit of shared purpose. In spite of the freezing temperatures, he gave away his warm coat and then nearly froze himself. Then he told a mythic tale from the time when “humans had stopped listening” to nature and the animals stopped listening to each other. The story was punctuated with powerful drum beats that were both part of the story and kept us listening.

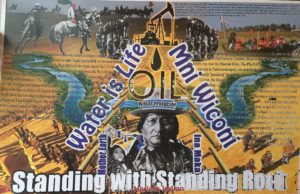

At Sacred Hoop, Robert “Running Fisher” Upham aka “Harlem Indian” honored the theme of “water is life/ Mní Wi with a large collage that included the history of the Sioux Indians as text in the background. This artist has also revived Indian Ledger drawings, the first descriptive images made by Indians in captivity in the 19th century.

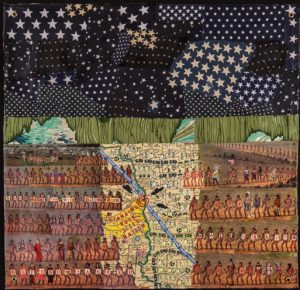

Seattle Theater Group and John Feoderov, another Seattle based Native artist, organized a one night exhibition benefit for the Water Protector Legal Collective, the on-the-ground legal support team for Standing Rock. Both Native and non-Native artists from around the country exhibited artworks that addressed environmental issues and “connections between land, culture and identity.” One of the works above by Deborah Faye Lawrence dramatically pinpointed the location of the protests in a collage.

“Protect the Sacred,“ a stunning and complex exhibition curated by Asia Tail (see image at top of post) at the Spaceworks Gallery open until February 16. (950 Pacific Ave. (Entrance on 11th St.)Mon – Fri / 1pm – 5pm, Third Thursday open until 9pm.) Tail, formerly on the staff of the Tacoma Art Museum, chose a cross section of 26 well-known and young Native artists to participate. She told me that hundreds of tribal affiliations were represented in the Seattle to Portland corridor, from the period of terminations, 1953-68 when the government took over valuable tribal land, and natives moved to urban areas. She herself is from an Oklahoma tribe.

![]()

Tail chose to focus on painting, sculpture, photography and installation. As we entered the door a large banner by Kaila Farrell-Smith” greeted us. A contrast to “Harlem Indian’s more realistic and text based homage, Farrell- Smith Mní Wičoní Banner, combines references to abstract basket patterns, and a political call to action “I explore the space that exists in-between the Indigenous and western worlds, examining cultural interpretations of aesthetics, symbols, and place. It is in this space I search for my visual language: violent, beautiful, and complicated marks that express my contemporary Indigenous identity.”

To some extent this idea permeates the entire exhibition. In work after work we see artists negotiating between native historical references and styles and contemporary approaches and content.

In the gallery, the photographs of Matika Wilbur, just back from Standing Rock, greets us first. Her subtle photographs always resonate with modernism combined with historical and Indigenous references, here in the hands of “Miss Helen, Last Carrier of the Lovelock Paiute Language,” 2016 we see a moving portrait as well as an homage.

Facing Wilbur’s photographs are two realistic watercolors by Yatika Starr-Fields. The artist usually paints intensely colored abstraction, but the impact of joining the protest at Standing Rock led him to record what he was actually seeing and provide a detailed description of the experience. “At the time this was painted, these two tipis were the northernmost structures in the whole Oceti Sakowin encampment. That day the air was alive with anticipation, and the scent of campfire smoke and sounds of all kinds echoed throughout the camp. With the setting sun casting its radiance on the changing colors of the distant fall trees and surrounding plains, the Missouri river seemingly created its own dominant horizon between past and present. This sacred hill – where burial grounds are present, and where many actions, prayers, and ceremonies take place – has been reclaimed as our own.”

Sara Stiestreem conceptual work celebrates rituals of basket weaving with rows of red circles and photographs of her hands in various specific actions. Fox Spears colorful abstractions could have been done by a white artist in the 1960s, but they are based on ancient basket patterns.

Marvin Oliver’s elegant work combines the best of native and contemporary expression

Erin Genia creates highly original ceramic sculptures with hard core messages like Facing/Not Facing: Toxic Devastation From Oil, just above) or Mobile Spill Response (top images) and finally, not illustrated, (Mni Wiconi: Water is Life Oil is Death.

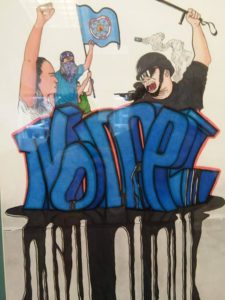

Next to Genia is the work of Samuel Genia, her fifteen year old son with a bold graphic statement.

Ryan! Feddersen’s interactive globe Micro Spill, plays on the idea of a snow globe, but when we pick it up we discover it has black magnetic particles that roll around, making a clear point about the despoliation of the land by industry.

I can’t enumerate all of the works. Suffice it to say that the exhibition takes time because it encompasses so many styles and ideas. Not all the artists specifically address the issues of extraction or its transportation. But they all tell us that contemporary native art is flourishing and provocative. All of the works are on sale and a percentage of the sale goes to support the DAPL resistance. This resistance will continue, as the bringing of our dreadful new President will only make the need for Standing with Standing Rock, and all other resistance to fossil fuel extraction and transportation absolutely crucial.

As the story teller at the Sacred Hoop gallery put it. “Stories Heal. Find your standing rock and pull yourself together.”

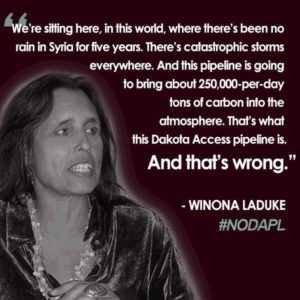

And let us give Winona La Duke the final word.