As we enter the exhibition “Zhi LIN, In Search of the Lost History of Chinese Migrants and the Transcontinental Railroads,” we face a large scale pale ink drawing of a wide railroad track that recedes rapidly into the distance in an empty, desolate landscape with the title “Golden Spike Celebrations-Chinese Workers’ Vantage Point of Andrew J. Russell’s Champagne Photo Site 2008.” Here we see the drawing with the artist posing in front of it.

In the drawing, there is no one in sight. And that of course is the point.

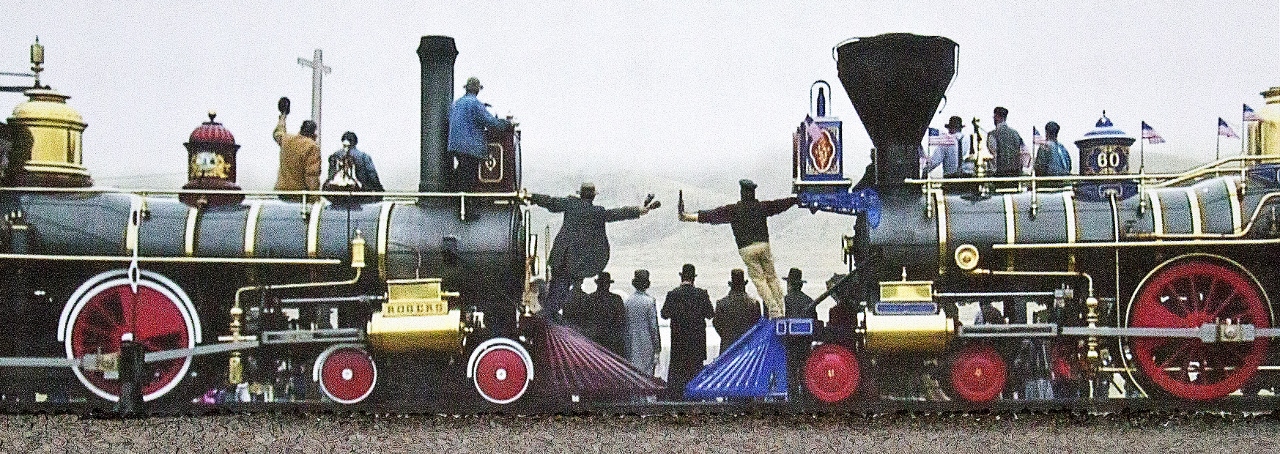

At Promontory Point Utah, on May 10, 1869, the transcontinental railroad connected the United States from one coast to the other. Andrew J. Russell memorialized the event in his iconic photograph “East Meets West at the Laying of the Last Rail.” In the photograph two engineers hang off the facing steam engines holding bottles of champagne, as the leaders of the two railroad lines shake hands.

The Chinese workers who constructed the railroad from California to Nevada are nowhere to be seen.

Every summer that event is re-enacted. Every summer the exclusion of the Chinese workers continues.

The backbreaking work by Chinese Migrants in subzero winter storms and blazing summers, hacking tunnels through solid rock in Donner Pass, working twice as fast as other workers, losing their lives in the hazardous work and through the vigilante murders of those who stayed on, all of that history had been expunged, deleted, unrecorded.

Zhi Lin, Professor of Art at the University of Washington, has spent many years unearthing scanty records and material remains, as he followed in the workers steps and empathized with their experiences.

He thought carefully how he could make their history come alive. He did not want to simply create imaginary realistic portraits. The result is this extraordinary exhibition.

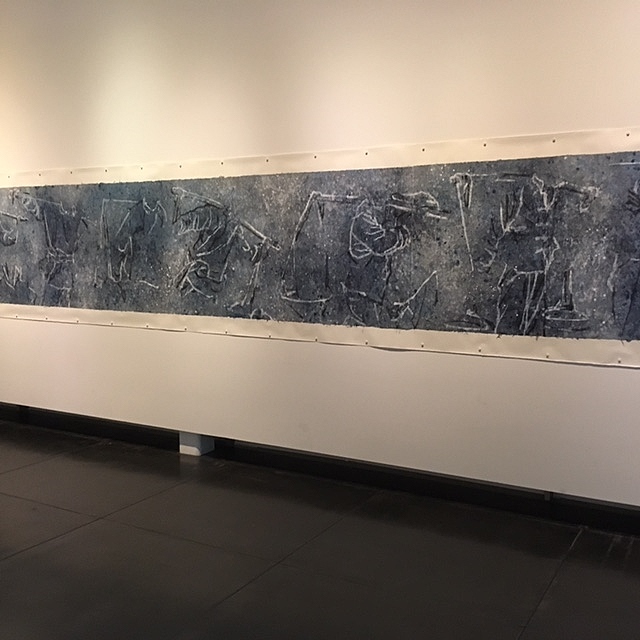

“Zhi LIN, In Search of the Lost History of Chinese Migrants and the Transcontinental Railroads,” ranges from almost abstract paintings that unscroll across long walls to tiny ink drawings.

Entirely filling one wall, a video projection of a slow moving steam locomotive moves toward a facing locomotive The engines stop with enough space for two engineers to hang off the front, as they clink their bottles. But in this film, we see the engineers from the back. Zhi Lin photographed the reenactment in 2014 from behind the trains. His film has the title “ ‘Chinaman’s Chance’ on Promontory Summit: Golden Spike Celebration 12:30 PM 10th May 1869, 2014.

The engines are in the forward plane of the film space, creating the effect of sitting directly on top of the 5 tons of rock ballasts, the supports for railroad tracks. The rocks are piled on the floor of the gallery space. Looking closely at the stones, we see names written in red. They suggest a giant graveyard for the Chinese workers with the materials of the construction of the track. But the names repeat over and over. The artist wrote the few names of Chinese workers that he found in railroad pay records, but he believes even those names, supposedly of leaders of groups of workers, were actually made up nicknames.

The film lays out the facts:

“During road construction, several thousand of [the Chinese workers] were badly injured and disfigured, and at least 1,300 lost their lives. The dead were never counted, nor have they been memorialized. From shallow graves along the roadbeds, some 12,000 pounds of bones, about 1,200 workers, were gathered and shipped back to China.”

Chinese migrants, originally drawn to the US by tales of golden mountains, often ended up working in mines. Their incredible work ethic and skill soon led them to be recruited for the excruciatingly difficult job of digging tunnels through solid rock in the Sierra Nevada what Charles Crocker, an owner of the Central Pacific Railroad referred to as “bone-labor.”

Lin forced himself to re-experience the conditions of these workers by revisiting the sites of their labor in the same weather conditions in which they worked:

“I descended deep valleys and icy tunnels, crossed rivers and streams, climbed snow hills, cliffs and summits, walked on flat-burned campgrounds and along railroad tracks and paid tributes to Chinese graveyards. I made a special trip … facing the winter elements.”

His delicate ink drawings of these sites ironically adopt the romantic approach to landscape practiced in Europe. This work (above) has the title “Railway Tunnels on Donner Summit, California – A Rectification to Albert Bierstad’t Donner Lake from the Summit” ( see Bierstadt below) which romanticizes the view and obscures the tunnel.

The next chapter of the story, The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, triggered vigilantes to expel the Chinese from communities in the Northwest and California, from Tacoma in 1885, Seattle in 1886 and from hundreds of other towns where racists burned entire neighborhoods and even massacred hundreds of people.

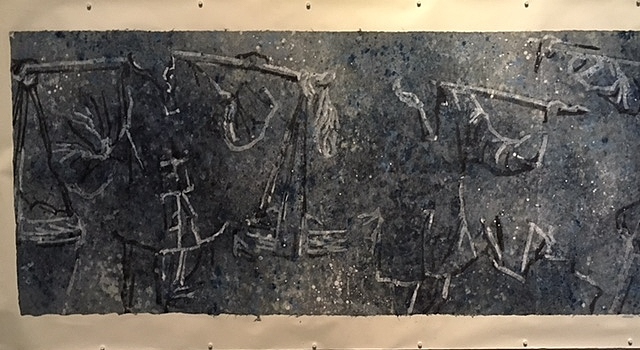

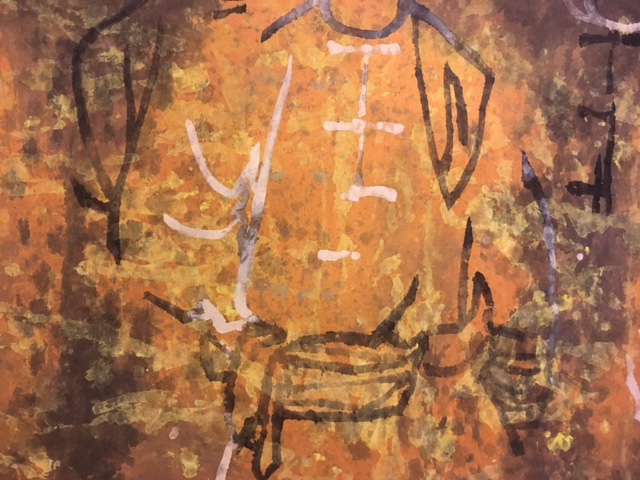

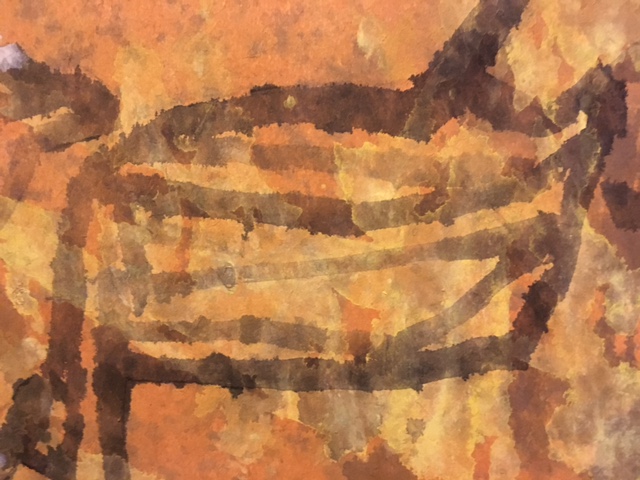

To honor these nightmarish tragedies, Lin turned to very long narrow almost abstract painting with titles like Snowstorm on the Cascade Summit Switchback” and “Sunset on Cascade” 2016. These intricate works on Chinese paper combine woodblock printing and painting; the closer we look, the more we see.

Lin anchored the abstractions with found objects and shapes as references to the vanished workers such as the frog fastenings on their jacket, or the ghostly outline of a worker carrying a pair of buckets on a long pole on his shoulders

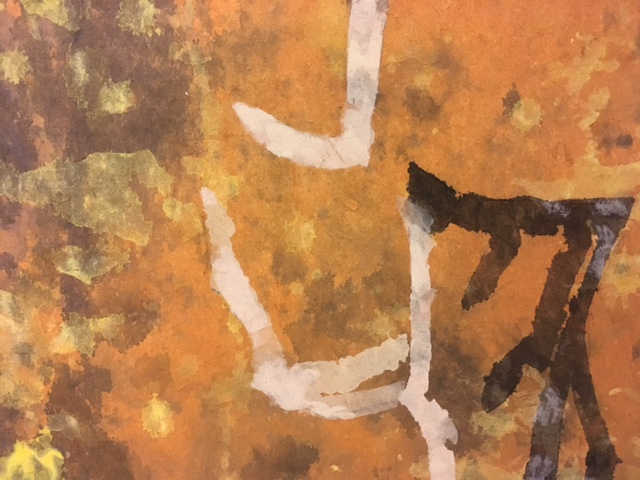

First we see the large hieroglyphic, calligraphic drawing which suggests a figure, then the stunning gestural detail and finally the layered abstractions of the background.

First we see the large hieroglyphic, calligraphic drawing which suggests a figure, then the stunning gestural detail and finally the layered abstractions of the background.

The last component of the exhibition focuses on Tacoma itself, and the horrifying expulsion of the Chinese on a cold rainy day in November of 1885, driven out by hundreds of vigilantes, armed guards, including even the Mayor.

For this topic, Lin created a more traditional scroll in scale and style depicting the 197 Chinese workers, their elders and their children as they struggle down Pacific Avenue, on the way to the Lakeview Railway station.

In addition, small ink drawings meticulously record the details of the expulsions and subsequent burning of Chinatown. One drawing is inscribed in part: “Elderly and sick Chinese rode on the wagons, the rest followed on foot, wrapped in blankets, carrying possessions on their backs. Some Chinese walked barefoot on the muddy road, and many cried.”

Another states, “The station master sold 77 tickets to the Chinese who could afford the train to Portland. Others were loaded on boxcars on a freight train next morning. For several days woebegone Chinese could be seen walking south along the tracks. Among the Chinese, two elderly people died from exposure.”

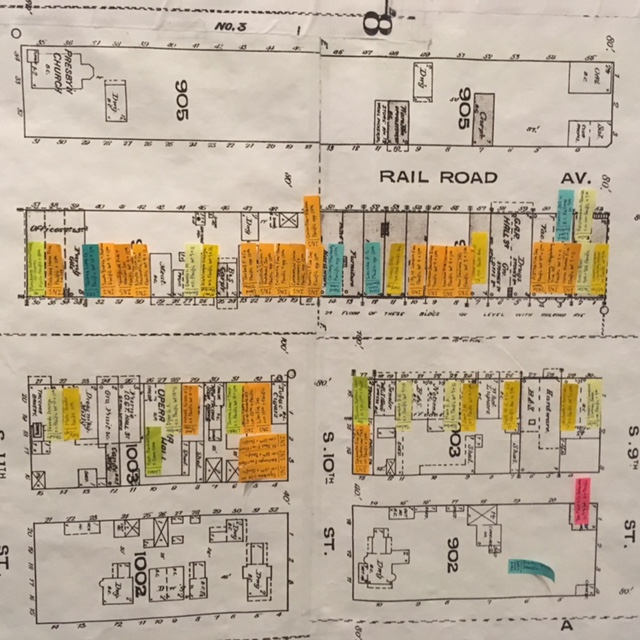

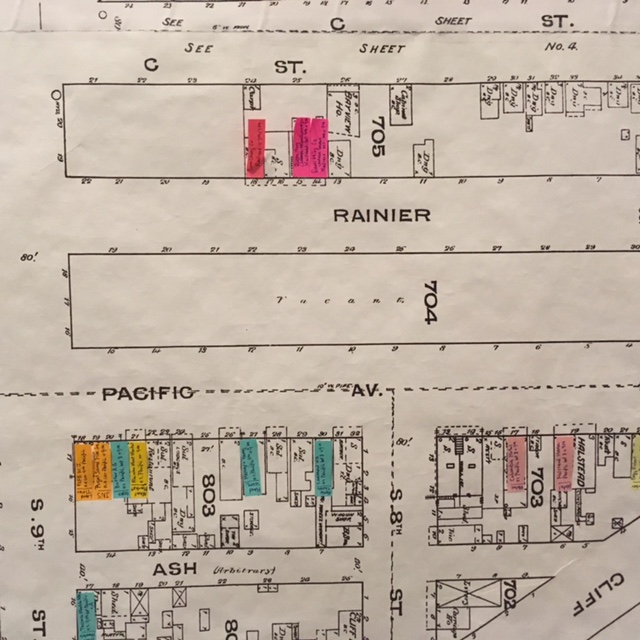

Lin pursued detailed research to create these works and captions. In the exhibition we can glimpse one part of his research, a map that marks the Chinese businesses and homes in pink, prior to their destruction.

Lin’s training in both Eastern and Western art techniques and conceptual thinking enables him to draw on every style, and transform it to tell this story, so crucial to changing our understanding of the history of the US.

Congratulations to the Tacoma Art Museum for supporting the painful exposure of a part of the city’s history that had been forgotten. The exhibition continues until February 18, 2018. It is accompanied by an thoughtful and fully illustrated catalog.