Part I

Phong and Sarah Nguyen Break into Blossom 2017 with Justin Shaw

As our horrifying President falls for the bullying of North Korea with threats, I am revisiting some important art work that addresses the topic of nuclear war and nuclear pollution. In Seattle, a current exhibition at the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific Experience called “Teardrops that Wound: The Absurdity of War” gives us stunning references to the bomb by descendants of survivors.

“The undetonated bomb is half sunken and surrounded by fallen cherry blossoms.”It is inspired by a chapter in Phong’s book “Einstein saves Hiroshima.” Phong imagines “icons of history make a different choice” it suggests a far different outcome from the death and destruction of dropping the bomb

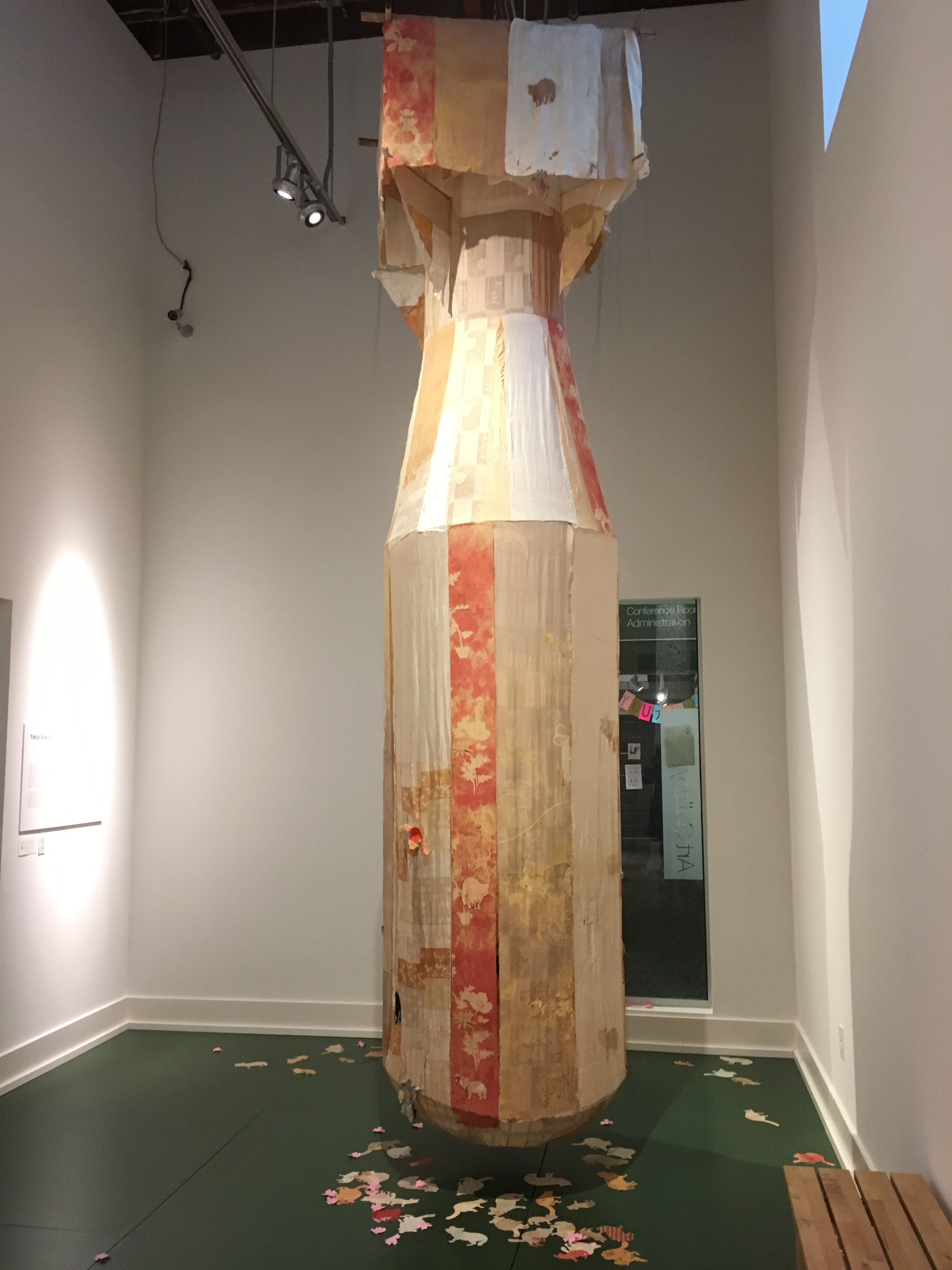

Yukiyo Kawano Sad Tale of Tanuki

Yukio Kawano suggests the imaginary creatures of mythology in this “Little Boy” created from kimonos from Fukushima sewn with the artists own hair.

Part II History

2001: PLUTONIUM, MARCH 28, 1941,

Ann Rosenthal and Stephen Moore addressed this topic for many years and in many formats. They visited the sites of the tests, of the development of plutonium in Hanford Washington ( now being touted as part of the new Manhattan Project National Historical Park) and they went to Japan to the cities where the bombs were dropped.

Here is a review I wrote of their work from 1995. It is still important today “Nuclear Bombs, Nuclear History and Postmodern Politics” first published Reflex Magazine, 1994 – 1995, Seattle ( I cut out the postmodern politics section, but you can read it on my website)

After a burst of attention following the television “docudrama’ simulating the aftermath a nuclear attack “The Day After, (aired by ABC November 1982) and the disastrous accident at Chernobyl (April 25, 1986) nuclear power is currently “out of fashion” as a publicized subject for political art. But as the risk of nuclear components in the hands of terrorists continues, as do the health hazards of its production and storage, nuclear power is still an issue and a presence that we cannot afford to forget.

The recent (1995)uproar in Congress and among veterans’ groups over an exhibition at the Smithsonian Institution in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the dropping of the bomb reveals, atomic bomb history and nuclear power is still a carefully edited story. Ann T. Rosenthal and Stephen Moore in their installation have produced a reminder, in response to that same anniversary, of the ongoing presence and dangers of contemporary nuclear power as well as a roadmap of that edited history.

“Infinity City” overlays and juxtaposes cultural artifacts in many media as a metaphor for the multi-layered and ambiguous presence of atomic and nuclear power in our lives and in history. It avoids the predictable quick hit cliches-there are very few mushroom clouds and they are small, encompassed in other imagery. The emphasis is much more subtle. It asks us to use our intellect as much as our emotions.

The exhibition has several parts.

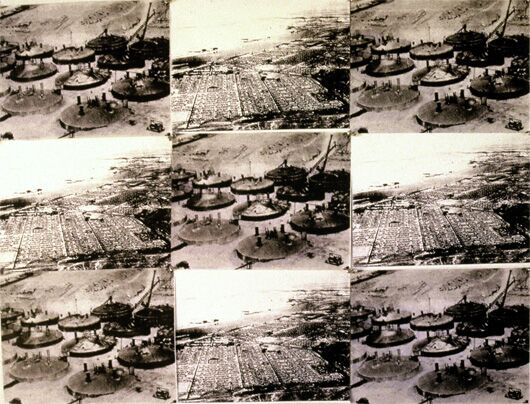

The first part, “Tricity Trinity” marks a US map with the atomic triangle, the Pentagon, Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, and the Hanford Nuclear Reservation. Invoking the latter are blown-up blue line prints of tight rows of the lethal, leaking waste storage tanks at the Hanford Plutonium Plant. The waste tanks are paired with the orderly suburban houses of nearby Hanford, Washington, a community built after obliterating the preexisting community.

The second part of the show “Eternity Ignored” includes manipulated photographs of the abandoned runways at the military base at Tinian Island in the north Mariana Islands (halfway between New Guinea and Japan).

An eerie antithesis to a South Sea paradise, the wide, empty runways have small signs landscaped with flowers that mark the deep pits used only once, for loading the huge atomic bombs Little Boy and Fat Man onto B 29 planes. The site is striking, according to the artists, for its lack of historical documentation, its air of a military ghost town. That sense of the horrific transformed into the trite and the obscure is captured in their understated images.

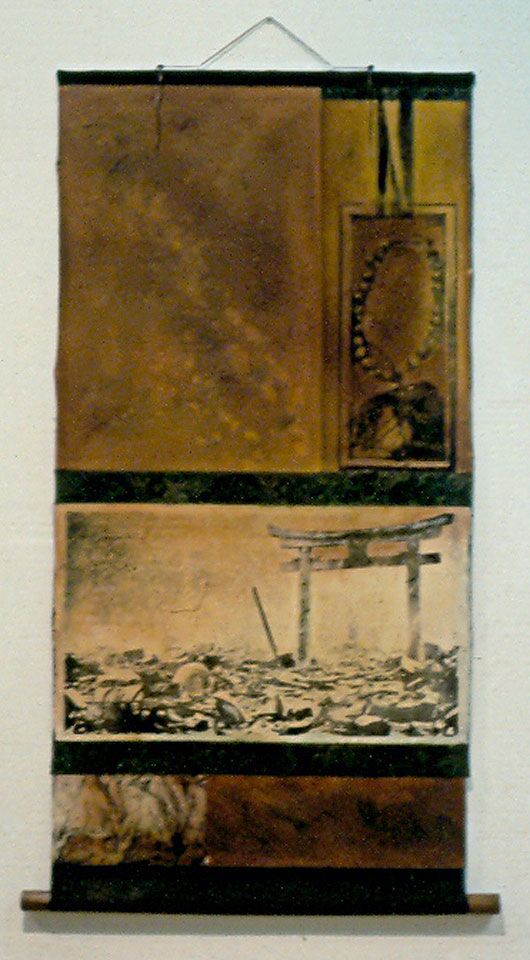

The third part of the exhibition is titled “Target Japan.” It includes paintings invoking Japanese scrolls that overlay an aerial photo of Hiroshima Ground Zero with the very young men of the crew of the B 29 and the current Peace Park at the site. . . .

Marking the back of the exhibition, and metaphorically casting its presence over the entire show, is a full scale black outline of Little Boy.

But for Ann Rosenthal and Stephen Moore these objects are only a point of departure. They are hoping to generate awareness, questions and even activism. On a table are books such as “Nuclear Culture”, “Missile Envy”, and “The Day the Sun Rose Twice”, as well as clippings about the current health problems from the plutonium production plant at Hanford. A news article details an exuberant Tri Cities near Hanford as the recipient of huge clean up funds that are ensuring the economic survival of the city for years to come.

The artists want to not only reach people with the subject, but give them possibilities for expressing their feelings within the exhibition itself. They provided an area for adding a work of art or a written statement. One such piece was by a Japanese student who remembered, in a stirring drawing, the shock of visiting the Hiroshima Peace Museum as a child.

Residents of Eastern Washington State commented that they have relatives who are downwinders from Hanford, relatives who helped build the bomb, relatives who fought in the war.

Most believe that dropping the bomb ended the war and saved lives. These responses add more layers to the cultural history of atomic and nuclear power and make the exhibition more effective than the use of a more controlled, didactic approach.

The artists have on ongoing involvement with the subject. They believe that “the atomic bomb changed our whole perception of reality and the future.” In 1982 they created several performances in Los Angeles as part of a group of six artists called UNARM. The group focused on the death and horror from just one nuclear detonation and sought to “raise the public awareness of the irreparable consequences, both physical and psychological, of the folly of nuclear proliferation.”

. . . . .

Rosenthal and Moore communicate by undermining a simple and dominant cultural myth – that American technological brilliance solves problems, wins wars, and of course “makes everything all right.” Underlying it is our knowledge that technology is actually destroying the planet both physically and psychically, in the microcosm and the macrocosm. Infinity City presents fragments of the invisible presence and history of the largest and most obvious psychic and physical manifestation of that destruction and of the misplaced values of our culture, atomic and nuclear energy.

Note: This article was written in 1994. The project continued for many years. Stephen Moore died in 2006, but Ann Rosenthal continues to be actively engaged with opposition to nuclear weapons.

See Ann’s own discussion of her work.

Part III “It is Heavy on my Heart” (2002)

Artist’s Statement Gail Tremblay

Gail Tremblay Lung and Diaphragm Tumors in a case of Epithelial Mesithelioma with embedded sound

“I first became aware of the effects of nuclear pollution on reservations in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s when I began reading about rising cancer rates on the Navajo reservation. Because piles of radioactive dust and rock (tailings) from uranium mining had never been cleaned up by the corporations who did the mining, people living in areas on the reservation where the mining was done were suffering from the health problems associated with long term cumulative effects of radiation exposure.

Next, I heard about the effects of the Nuclear Testing of Atomic Bombs in Nevada on the health of the Shoshone peoples there. Then I heard about the negative health effects on Yakama and Coleville people caused by radioactive emissions and spills from the power plants at Hanford Nuclear Reservation where the earliest reactors were used to enrich uranium and create plutonium for the first nuclear bombs.

During the long period of the Cold War when several countries were testing nuclear weapons, people around the Arctic were exposed to large doses of nuclear fallout, and I began to hear stories about the health effects on Inupiat and Inuit peoples. Because indigenous people in all these places hunt and/or fish and gather local plant foods also exposed to radiation, native people concentrated much higher rates of radiation in their bodies than many non-native people in surrounding areas.

People who lived a less tradition life style and bought food in grocery

stores that was shipped in from less contaminated areas would still suffer from health problems, but generally there exposure levels were lower unless they grew and raised their own food.

At the same time, the U.S. government supported corporations like General Electric to develop Nuclear Power Plants, and this policy generated an incredible nuclear waste problem. U. S. officials eventually decided to look to reservations to create Monitored Retrievable Storage (MRS) facilities to house that waste while a permanent storage facility was built.

During the 1990’s, large amounts of money was paid to several tribal governments to do feasibility studies. When people in the various tribal communities being studied learned that their reservations were being considered, movements to stop MRS sites from being built divided communities into factions where large numbers of people didn’t want to risk radioactive contamination if an accident occurred. The U.S. government targeted reservations because they are by treaty sovereign nations and U.S. citizens in surrounding communities and states have no control over them. Many communities are still feeling the negative effects of this U.S. policy in their relationships and on their lives.

Current U.S. nuclear policy calls for building a permanent storage facility at Yucca Mountain, a place where much of the early testing of Atomic Bombs was done. Yucca Mountain lies on an earthquake fault and both the Shoshone people and millions of non-Indian citizens of the state of Nevada oppose this policy. Current U.S. Nuclear Posture Statements also call for the building of new nuclear power plants that will create more nuclear waste,the development of new, small nuclear weapons for use in “limited” nuclear wars, and the testing of these new weapons. One wonders how many more people

will suffer from rising cancer rates, birth defects and other health

problems related to nuclear pollution if such a policy is implemented.

Such policies are dangerous for all people on the planet, not just future enemies of the United States government, the only country to use nuclear weapons in war. But for people in indigenous nations who are most likely to be impacted by future mining, testing, or waste disposal, current nuclear policy statements are plans by the U.S. government to commit more, possibly genocidal, international crimes against humanity. It is immoral when a government endangers the right of peoples in nations inside their boundaries

to a healthy life practicing their traditional life ways on this planet,

Mother Earth, who has sustained life for countless generations. In the face of such policies, it is time for all Americans to stand up for the health of the planet and the health of all the beings on it. One needs to think about rising cancer rates among friends and relatives and to chose leaders who will make policies that are not quietly killing the people one loves.

Decisions that are not good for people being born Seven Generations in the future are bad decisions. No one should choose leaders who make bad decisions.

Gail Tremblay