I met Hanaa Malallah in 2007, just after she left Iraq under duress. At that time I wrote a long blog post about her work which I link here.

Here I am in London again, ten years later, and, very fortunately, Hanaa is having a solo show. She is currently based in Bahrain as an associate Professor of Art at the Royal University for Women there.

She is teaching art and theory. Hanaa has a Ph.D. in the Philosophy of Painting with a thesis on “Logic Order in Ancient Mesopotamian Painting. ” ( I remember visiting the British Museum with her in 2007 as she explained the meaning of the Royal Game of Ur to me.)

While a young artist and professor in Iraq she stayed in the country through the Iran/Iraq war ( 1980-1988) and the Gulf War ( 1990 91). She also stayed during the period of severe sanctions during the 1990s, when she was unable to travel, and supplies were limited in every way. During that time she immersed herself in historical Mesopotamian art as a crucial reference point in her work.

The present exhibition “From Figuration to Abstraction” at the Park Gallery in London is both fascinating and unexpected. A friend of hers in Baghdad sent a selection of her work from primarily the 1990s to London. So the current display includes those works.

As we stood in front of them, she said that each one represented a major show that she had in Baghdad . Many works were looted from her home in Baghdad after she fled the country. Her work also hung in the Modern Art Museum in Baghdad, which was looted. A team of artists and curators have recovered some of those hundreds of works in street markets, but many hundreds are gone, and the museum itself is now a shadow of its former self. Many of the works are in storage, and the museum has no funding. Only 200 works are on display out of the original collection of 8000, 7000 of which were looted.

So we have four  early self-portraits. Here is one of them from 1989 that reveals an intelligent and probing and perhaps tragic person.

early self-portraits. Here is one of them from 1989 that reveals an intelligent and probing and perhaps tragic person.

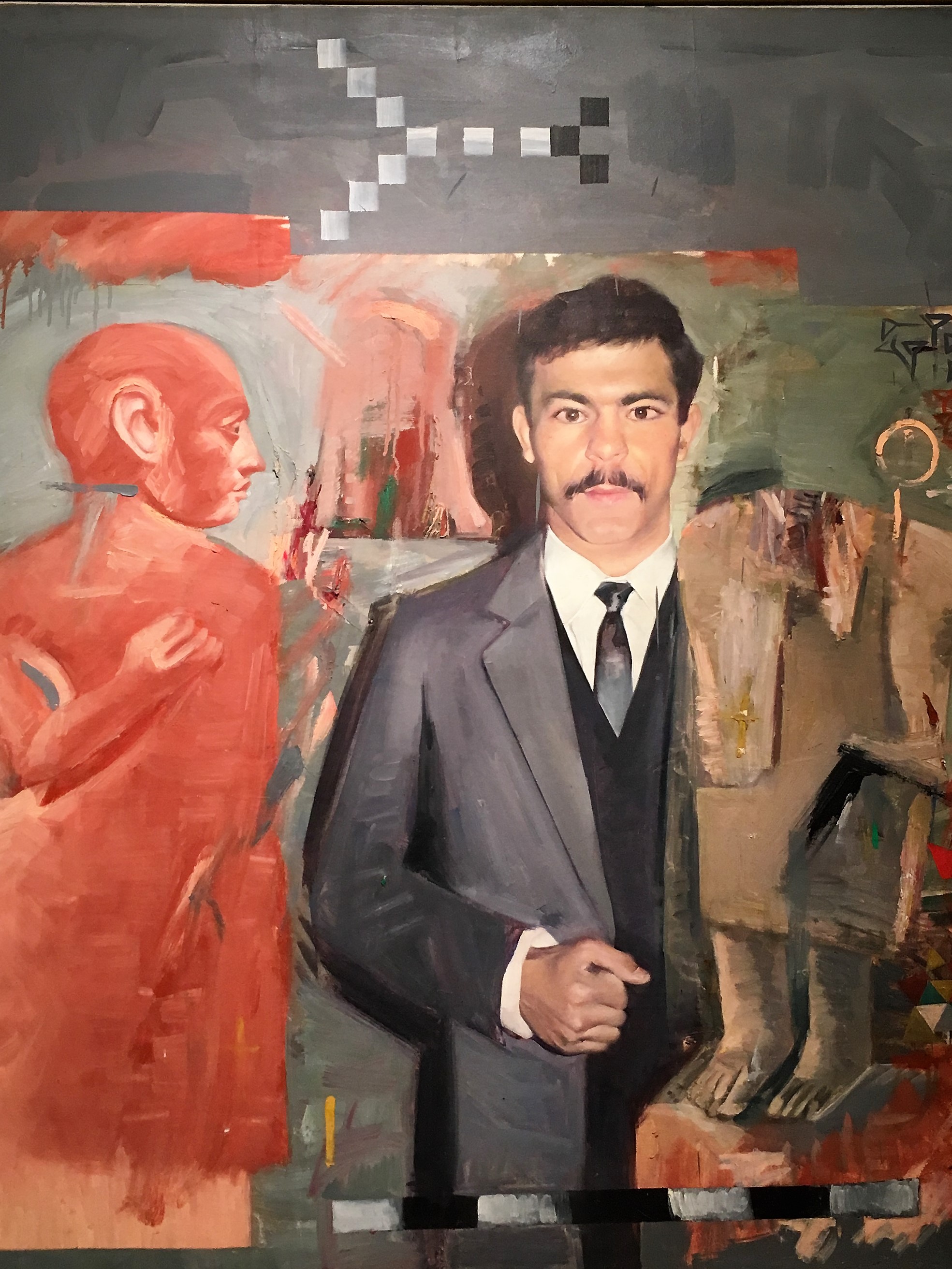

The next fascinating surprise is the 1991 painting called The Guard.

A face with piercing eyes looks directly at us: he is a museum guard at the National Museum of Iraq. He is shown between two mesopotamian sculptures, one seems to look at him, as though the artist is suggesting a direct communication between the ancient stone statue and the contemporary Iraqi.

Half lost under abstract brushwork is a second statue, a seated figure, perhaps Gudea of Lagash. I am giving you details of the lower right hand corner of the painting as it descends into increasingly complex abstraction and brushwork

Keep in mind that this is the same museum that was looted at the time of the 2001 invasion of Iraq.

In this single painting we start to see the artist’s connection to the history of Mesopotamian art as well as her stunning technical facility.

Sketch of Alwarkaa Wall Temple Artwork 1991 also pays homage to a hugely important site, also known as Uruk in Mesopotamia.

We see in the detail meticulous geometry interrupted by a scarred surface. We all remember the horrendous pillaging of the National Museum during the ignorant American occupation of Baghdad. In 2006 a report recorded that 10,000 objects were still missing. We know that the dysfunctional Iraqi state is not protecting its ancient sites.

Donny George, the heroic director of the National Museum, himself had to flee at the same time that Hanaa left in 2006. He personally managed to recover almost half of the antiquities stolen during the disastrous American invasion. He died of a heart attack at age 60 in Toronto Canada. I was fortunate to hear him speak at the College Art Association as well as to meet him at an exhibition of Iraqi art in New York City.

Other works by Hanaa are works from the 1990s that emphasize pattern. This is an example from 1993 and a detail where we again see the way in which the regular pattern is interrupted by the black dripping form in the upper left. The geometry is based on ancient symbolism, the black shapes look like an invasion.

are works from the 1990s that emphasize pattern. This is an example from 1993 and a detail where we again see the way in which the regular pattern is interrupted by the black dripping form in the upper left. The geometry is based on ancient symbolism, the black shapes look like an invasion.

Here is a detail of another of these pattern works that from 1999

And 2002, not long after the war started and the museum was looted. We experience both her deep commitment to the historical symbolism of Mesopotamian art and her sense of tragic loss as her homeland and its art is destroyed.

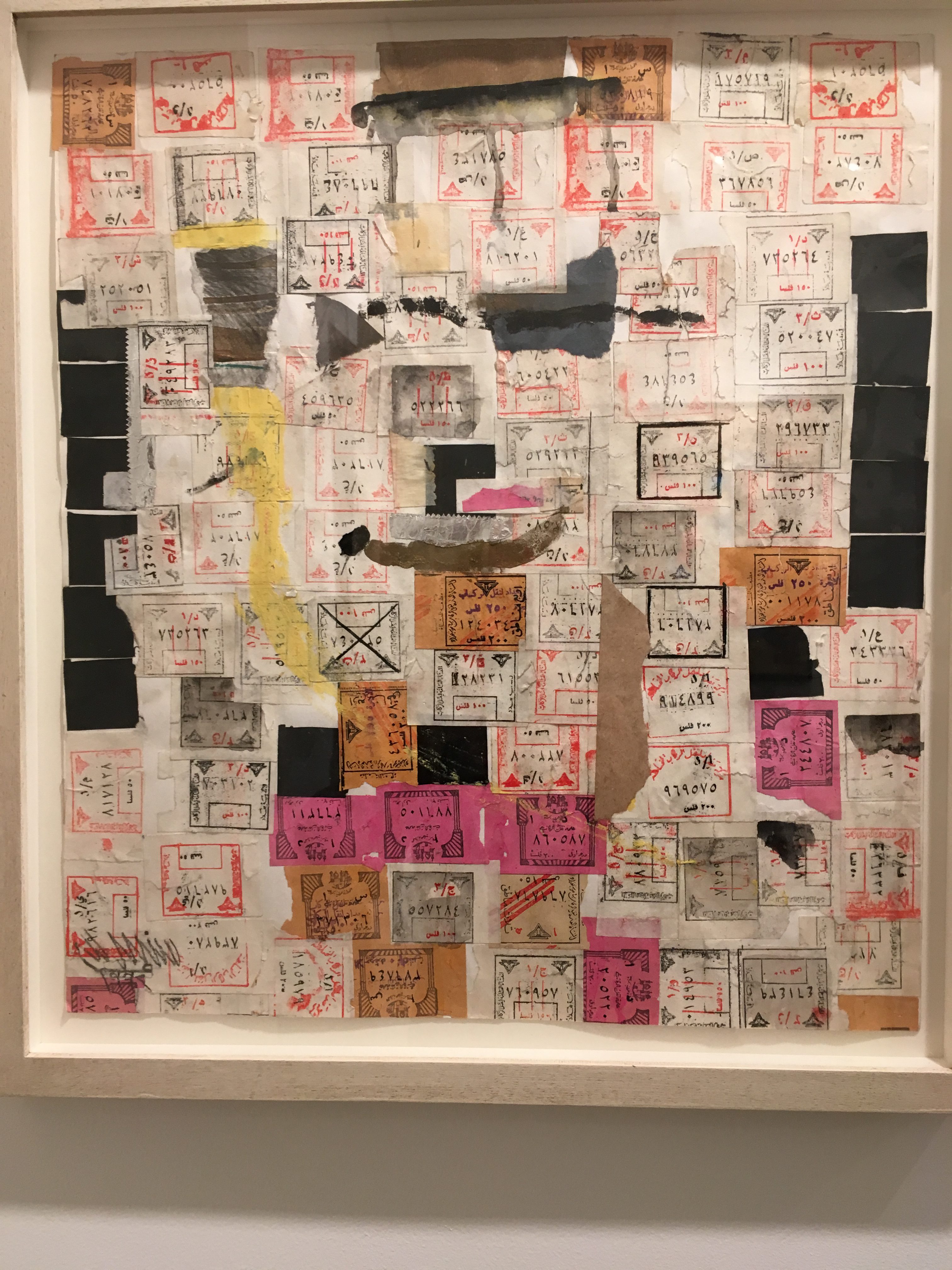

In addition there are several paintings from the 1990s that reflect the result of sanctions on Iraq’s artists. One 1993 work is composed of bus tickets,

another scraps from the street.

Many other types of work appear in the show, showing Hanaa’s willingness to experiment, meticulous pencil marks that suggest counting, colored squares , patterned works based on ancient references.

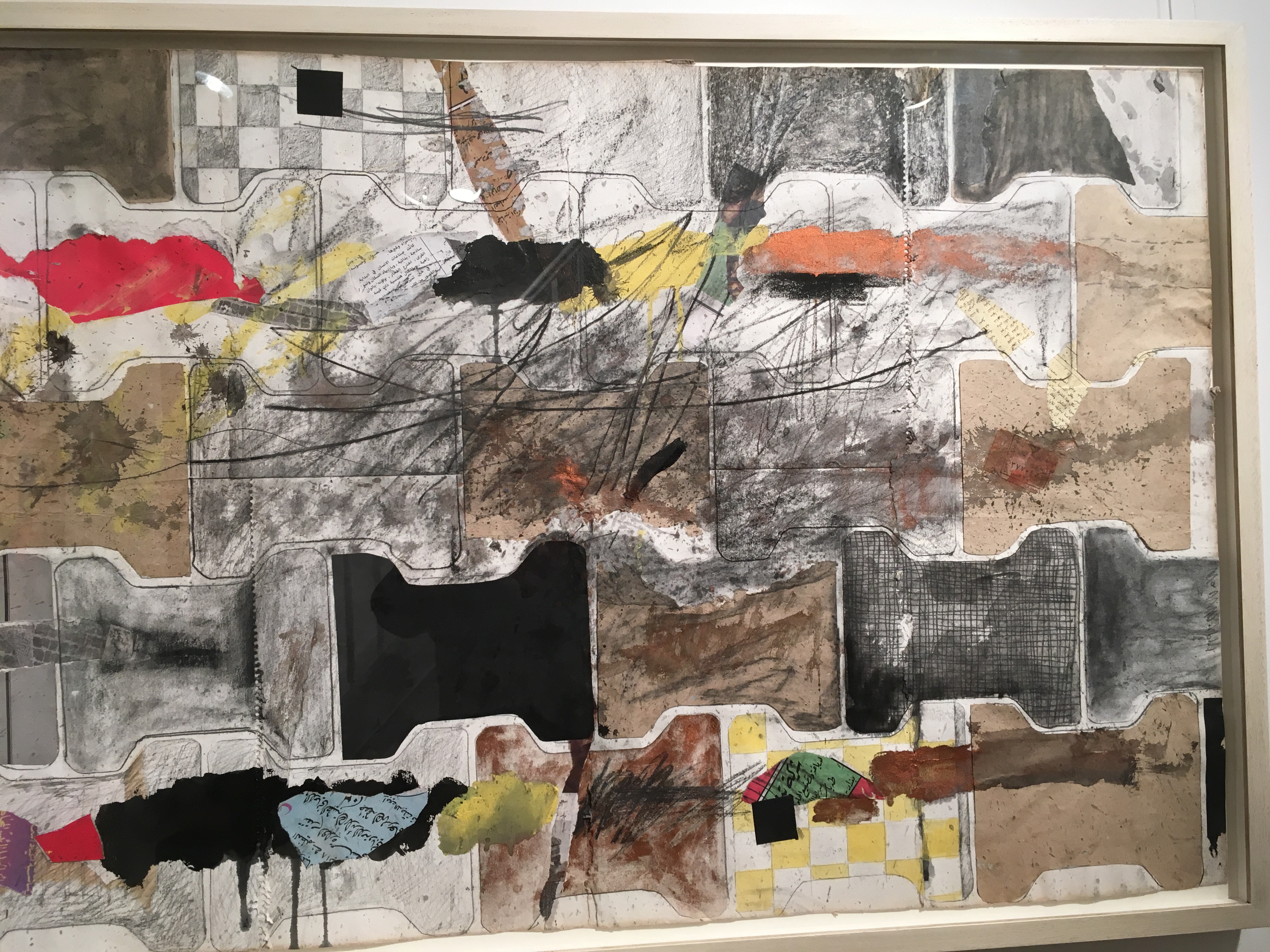

For me, The Dawn, 1995 was the most dramatic. Smaller than many of the other works, we see a series of carefully constructed compartments made from canvas, overlaid with energetic black and white paint strokes that suggest violence. This is a detail.

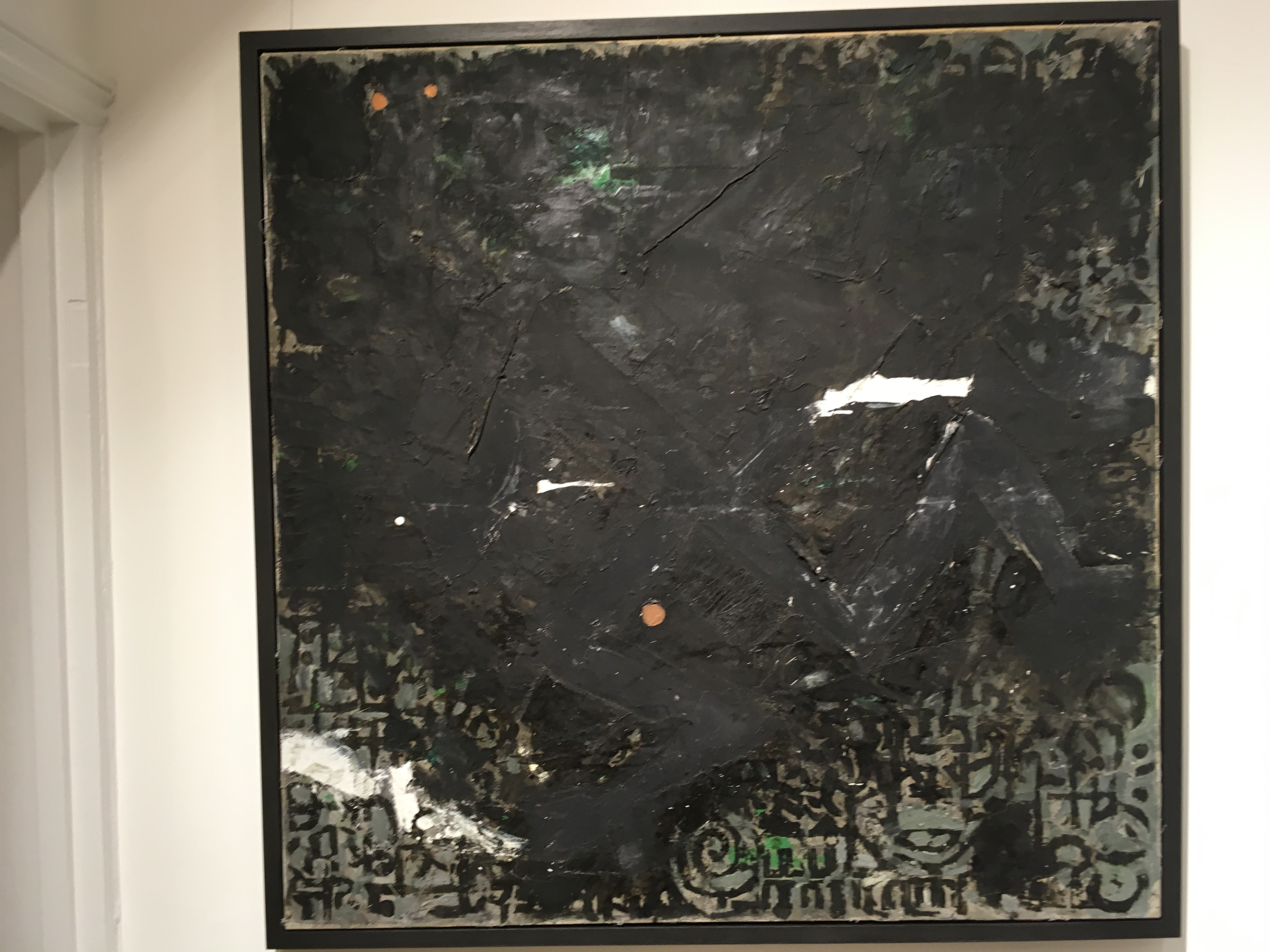

Last we have Signs 1999 where the blackness is almost covering the underlying details referring to ancient symbolic patterns. 1999 is before the great catastrophe, but it feels predictive to me.

Hanaa’s work is also included in the current exhibition at the Imperial War Museum called Age of Terror: Art Since 9/11. I will be writing about that exhibition next.