Art and Politics are everywhere in London at the moment. Whether it is the Imperial War Museum’s Art of Terror, the Migration Museum, an entire wing devoted to Art and Society at the Tate Modern, Red Star Over Russia at the Tate Modern, or the audio tour “The Darks” describing the former prison at the site of the Tate Britain, there has never been a time when socially engaged art was more prominent here

And that doesn’t even count the events in honor of the anniversary of the Russian Revolution such as Pussy Riot’s immersive evocation of the prison system in Russia or the play by Dostoevsky The Demons (The Possessed), creatively performed in a crumbling church in Spitalfields.by Split Moon Theater. In addition, there are references to Brexit in the play Albion by Mike Bartlett and the troubles in Northern Ireland in Jeb Butterworth’s play,The Ferryman.

Whew. Where to begin. I am fortunately spending nine weeks in London and feeling quite overwhelmed with so much to write about. I have submitted two articles for publication on the Imperial War Museum exhibition and the Migration Museum, so I will return to them in a separate post

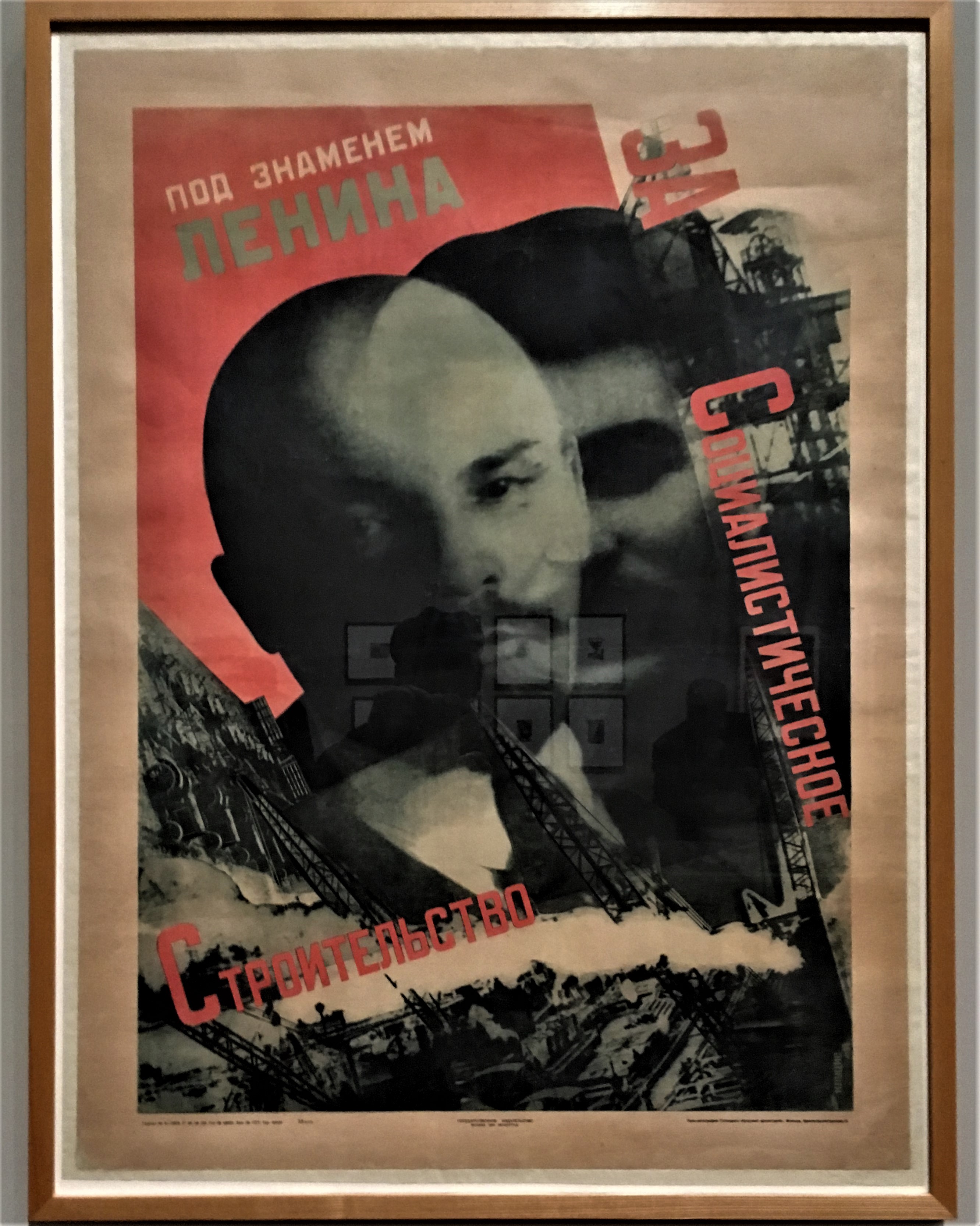

In honor of the100th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, the extraordinary collection of David King is on display at the Tate Modern in “Red Star Over Russia.” It includes the history of the Russian Revolution from the last days of the Tsar to the death of Stalin. The variety of visual materials stunned me, ranging from postcards, journals, banners, and informal photographs to the famous fotomontage designs of the late 1920s. Altered photographs have heads cut out as they are declared “enemies of the state.” This is only a small selection of King’s collection of doctored photographs ( or of his collection as a whole) , first published in 1999 as The Commissar Vanishes. Grim mugshots of people, ranging from Lenin’s associates to peasants, who were executed in Stalin’s purges in the late 1930s fill the center of one gallery, together with each of their biographies. On loan were some of the huge paintings sanctioned by Stalin in the socialist realist style.

The historical trajectory of the exhibition starts in the end of the tsarist era passes through the 1905 revolution, World War I and the Bolsheviks in 1917 to the oppressions and murders of the late 1930s through the nightmare of World War II when posters endeavored to create nationalistic fervor as the Nazis invaded ( and after Stalin had executed 25,000 high ranking officers between 1937-41)). It ends with the post war era of continued nationalism until Stalin’s death in 1953: we see him lying on his deathbed.

The moments of change appear vividly in the arts displayed. We could see the photographs of the earliest revolutionary sculpture that did not survive, because it was made in plaster, giant sculptures in public places, then the thrilling development of a new vocabulary for a new society in photography, design, film, painting, printmaking and all other media.

One room included a few of the now well known visual artist partnerships of that era: Valentina Kulagna and Gustav Klutsis, Aleksandr Rodchenko and Vavara Stephanova, El Lissitsky and Sophie Lissitzky-Kuppers. The last two pairs designed photomontage displays and magazines throughout the 1930s.

Gustav Klutsis was executed, but many visual artists survived, although disillusioned and compromised. We saw angled abstractions and upright realism by the same artists juxtaposed on a single wall.

Musicians such as Dimitri Shostakovich and Sergei Prokovie also survived the purges with careful accomodations. Shostakovich was attacked for being too avant-garde, but managed to create his fifth symphony as a sop to Stalin, with more traditional musical reference points. (I was fortunate to hear this symphony the same day I went to the exhibition. The drums were regular, loud and repeated, they could be a parody, a warning, or a military march. Mahler’s soothing rhythms dominated one whole movement; Bach and Beethoven as well as Handel permeate).

David King’s life long obsession as a collector was to rescue Trotsky from visual oblivion. Stalin had not only exiled him and had him assassinated, he obliterated his face from every photograph and destroyed his books throughout the USSR ( event today he is not acknowleged). King resurrected him through his personal sixteen year search for images of Trotsky. He wrote a photographic biography of him in 1986. Three black and white film clips in “Red Star” gave us Trotsky at meetings giving speeches, bringing him back from visual obliteration in the story of the revolution inside the Soviet Union.

But of course Trotsky’s ideas have lived on continuously outside the USSR, in the books he published such as Literature and Revolution, 1925. In the late 1930s as Stalin systematically executed the founding fathers of the Bolshevik revolution, as well as hundreds of thousands of others, far away in the US Trotsky became the alternative to Stalinism for some members of the Left. His memorable positioning of art, culture and intellectuals in general as the vanguard of Revolution is certainly the heritage of the early days of the Bolsheviks and the 1920s when artists were spreading the ideas of the Revolution across the massive USSR.

In the exhibition we see the vanguard of culture from the earliest monuments erected to Lenin and Marx, the agit prop trains, the banners from the far East encouraging the new society, the posters calling on Muslim women to uncover themselves, and much more. The sweep of the material is dazzling and at the same time intimate. We see rare photographs of Stalin’s wife (who committed suicide), we experience the exuberance of the artists, we witness the nightmare of the purges. Above all, we think about the terror of an insane leader with too much power.

The emotional roller coaster of the exhibition echoes the joys and horrors of the USSR itself in the 20th century.