The despoliation of Indigenous reservations through fossil fuel extraction, pipe lines, uranium mining, and many other disastrous environmental policies, is a subject of the work of several prominent

Indigenous artists. Currently on view is the work of John Feodorov in the exhibition “In Red Ink,” curated by RYAN! Feddersen at the Museum of Northwest Art, La Conner

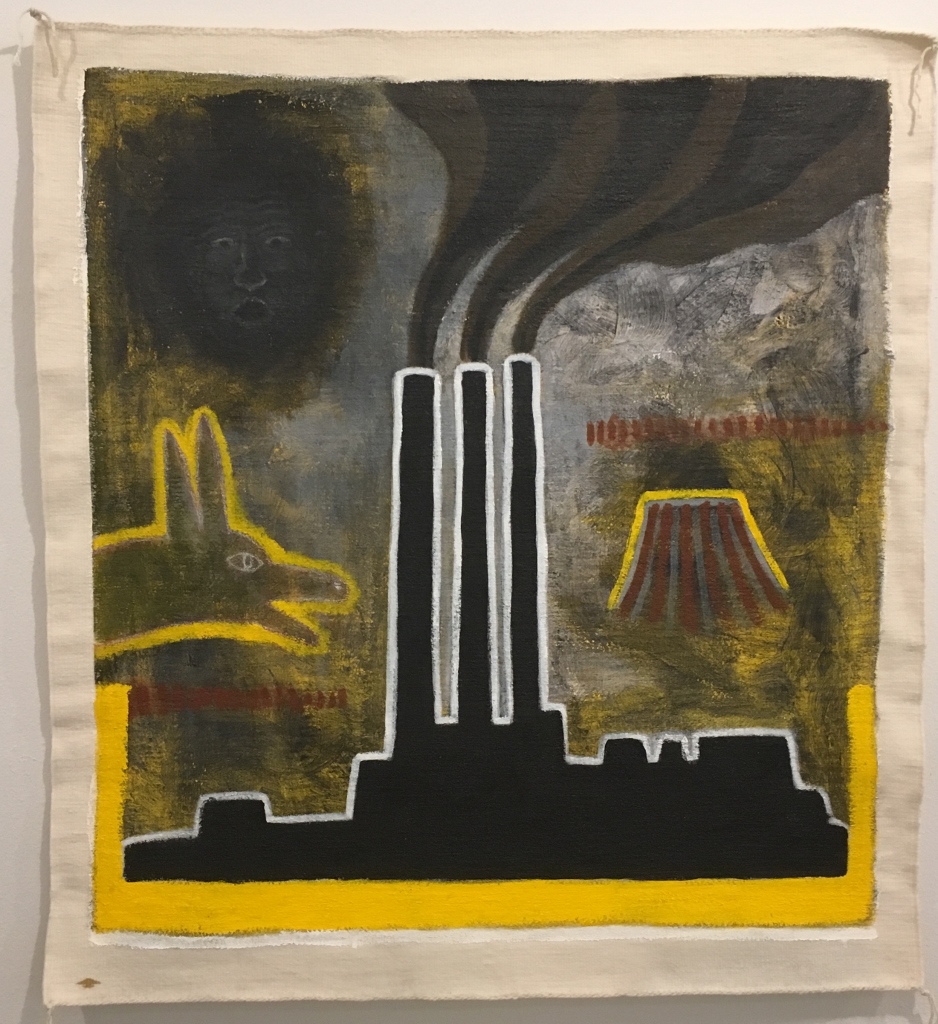

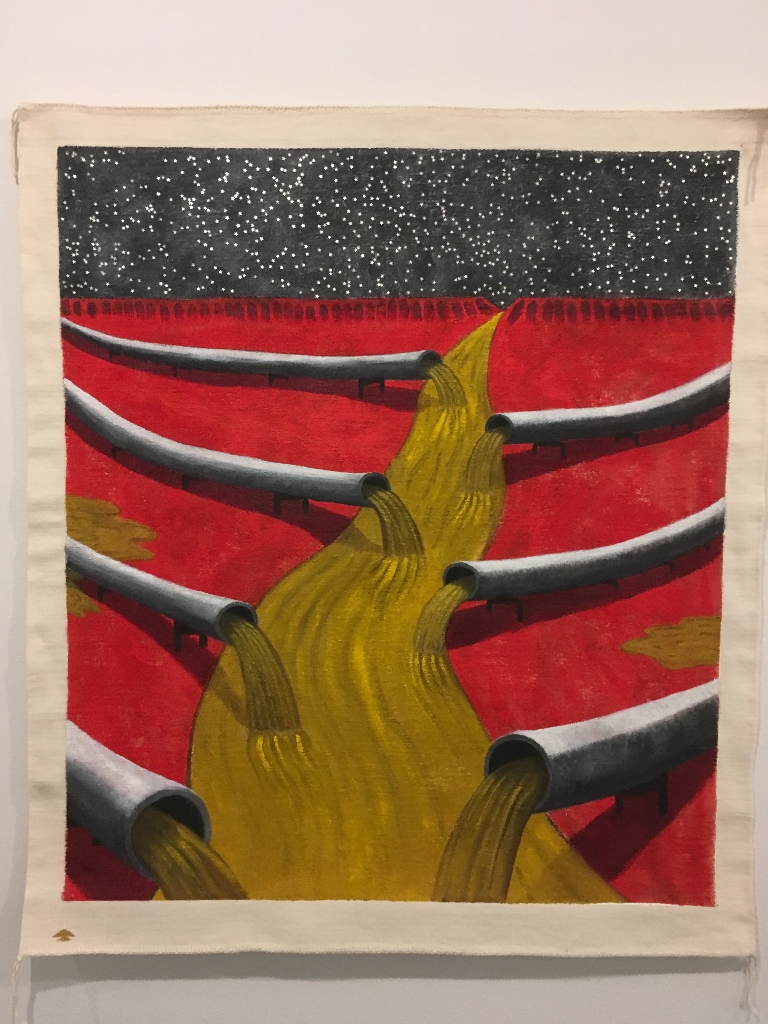

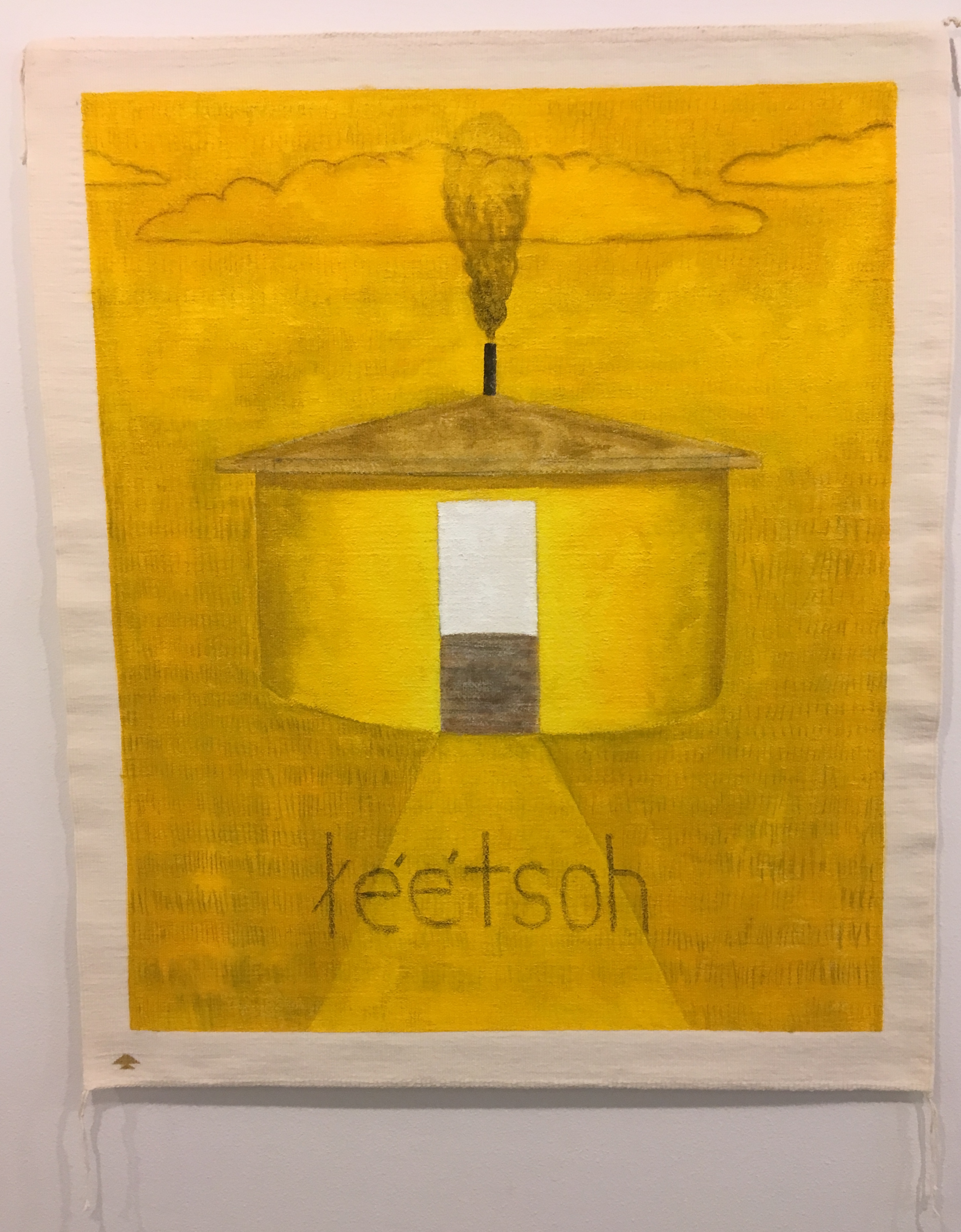

His four part work “Desecrations” :

#1the Coal plant

#2 the pipe lines

#3 the yellow radiation house

#4 fracking cracks in the earth

He painted these images on specially woven white Navaho rugs created by Navaho master weaver Tyra Preston.

Feodorov explained that as he painted on the rugs, he felt he also was committing an act of desecration:

“The series responds to ongoing environmental threats to traditional Diné lands and communities (including toxic pollution caused from uranium mining, coal burning, and fracking), as well as the exploitation and pollution of indigenous land around the world. But, it also refers to my hesitation in painting upon Tyra’s beautiful weavings.

“Just as Native lands are under constant threat, so are Native cultures. For me, these rugs act as metaphors for both land and culture. By painting upon them, perhaps I have also desecrated them? My mother taught me that weaving is a sacred art, taught to our Diné people by Spider Woman. So it was with some hesitation and great respect that I decided to undertake this series. Understandably, Tyra asked many probing questions of me before agreeing to participate, as well as consulting with a Navajo elder/medicine man from her community. I wish to thank Tyra Preston for weaving these gorgeous rugs, without which this series could not have been realized.”

A second Navaho artist is addressing nuclear pollution on the reservation: Demian DinéYazhi’ (photo by Patrick Weishampel) is currently showing an installation at the Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington as a result of winning the Brink Award. His work includes poetry, sculpture, and video intersecting to create a powerful statement.

It begins with confronting us as viewers with a manifesto presented in segments on a video screen:

“By entering this space you have agreed

To become a lifelong agent

Against humanitarian

And environmental injustice

You have agreed to forfeit your racist misconceptions

of Indigenous identity & respect the sacredness

of Indigenous traditional practices

You are not stepping into the past or staring into a

Picture plane void of Indigenous inhabitants

You are not glorifying western historical inaccuracies

Or romanticizing the cowboys and Indians narrative

By entering this space you agree to never again place

Your hand over your mouth in a mock “war cry”

Or teach your children to be ignorant of the

Indigenous peoples whose land you

Have claimed as your own

From this moment onward you have agreed to learn

The history of the Indigenous ancestral lands

That were stolen & continue to be stolen

Through settler colonial violence

&environmental genocide

By entering this space you have agreed to center

Your politics, social movements & institutions

Of knowledge around the Indigenous peoples

Whose lives & cultures were forever altered

In pursuit of this post-apocalypitic

heteropatriachal colonial nightmare”

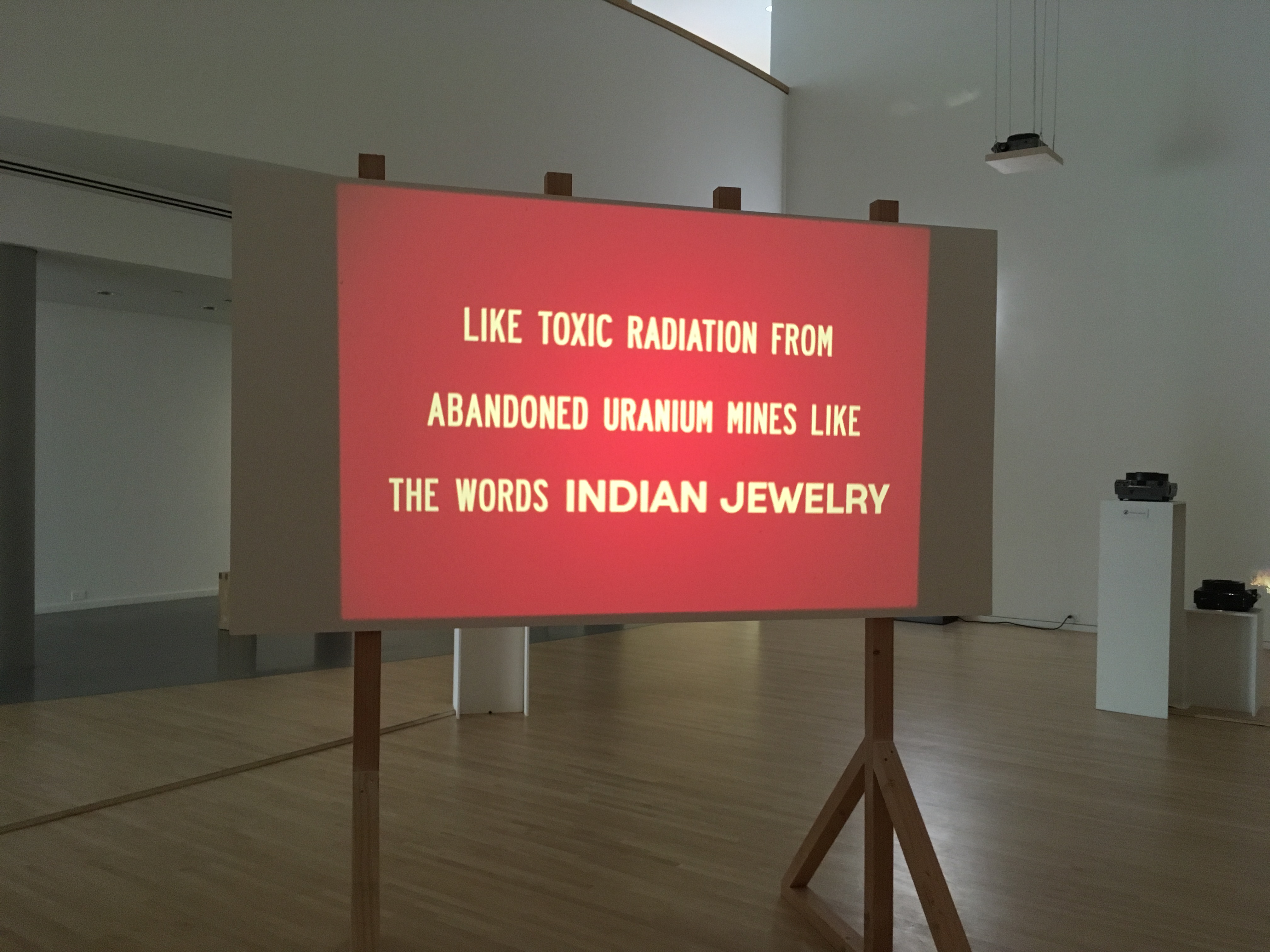

The space itself includes more poetry presented in a slide show and with reference to a huge uranium spill that occurred at Church Rock, New Mexico in 1979.

I am going to insert here Emily Pothast’s excellent article in the Stranger, based on her interview with the artist:

“In July of 1979, a breached dam at Church Rock, New Mexico, sent more than a thousand tons of radioactive waste tumbling into the Puerco River. Despite being the largest release of radioactive material in US history, the incident received almost no media coverage. Many residents who used the river for irrigation weren’t even notified, and the governor denied local requests to declare Church Rock a federal disaster area.

“Nearly three decades later, a team of public-health researchers linked the negligence to racism. The Puerco River flows through what settlers call the Navajo Nation—known in the Diné language as Dinétah—and the spill primarily affected rural communities on the reservation.

“Today, abandoned uranium mines dot the landscape like open wounds along what was once Route 66, lit up by garish neon signs advertising “Indian jewelry” to non-indigenous tourists. Many of these sites have not been cleaned up, and probably won’t be cleaned up.”

PHOTO BY EMILY POTHAST

“There are two pieces in the current exhibition by Demian DinéYazhi’ at the Henry Art Gallery that address this ongoing history head-on. The first is in beauty it is restored, a circular neon sign that glows like uranium but also reflects the balance of Navajo cosmology and the power of ceremony to make things whole again. The second is Hey Jolene, a visual poem projected from an analog slide projector onto a billboard-shaped screen. Its text extends the metaphor of toxic phosphorescence to the warm glow of an alcohol-soaked liver. Unlike many of the artist’s pieces, which pair texts with family photos and images of landscapes, the background behind these words is crimson.

“I use red a lot as a way to maintain an indigenous aesthetic,” says DinéYazhi’. “This is actually my finger pressing against the camera lens pointed toward the sun.”

“As for the text: “It’s about a friend who passed away a few years ago on her reservation. It’s one of the only pieces that addresses a specific individual, but this story line is very similar to every other indigenous person’s story within the Gallup region.”

“The artist’s hometown of Gallup sits just outside the Navajo Nation, some 17 miles south of Church Rock. DinéYahzi’ describes it as a colonized border town, a place where indigenous and Western worldviews intersect.

“The way land art has been constructed within contemporary art practice is to usually leave a mark against the land,” says DinéYahzi’. “Within an indigenous framework, it’s not about leaving your mark on the land, it’s about honoring a region as much as possible. Photography is a safe site to have an experience of the land that isn’t necessarily continuing in this legacy of taking or extracting.”

Another site of colonization that the artist’s work addresses is gender. “The Navajo tribe had four to five different gender systems,” they explain, adding that now there are elders who side with the assimilationist agenda as an expression of trauma incurred through settler violence. “Coming back to the ceremonial framework is a way to heal as a community.”

Thank you Emily Pothast for this clear explanation!

The third visual artist who has addressed contamination on Indigenous reservations for many years is Gail Tremblay. I have frequently reviewed her exhibitions on this topic which include video interviews, poetry by Arthur Tulee, large felt sculptures of lungs contaminated by cancer, and scientfic images of cancer contamination.

Here is one piece I wrote about at Daybreak Star gallery for the literary magazine Raven Chronicles in 2002:

“Iókste Akwerià:ne: It is Heavy on My Heart A room sized installation with large felt sculptures or organs with cancerous tumors, DVD, audio tape of singing, color copies of cancerous organs and cells, small felt sculptures of spiderwort, normal and irradiated.

The installation takes us over, rather than the other way around. It has a larger than life scale. Built out of felt, huge tumors grow on Lungs and Diaphragm and the Thyroid Gland. The cancerous tumors inhabit the room on the scale of human bodies, they invade our spirits, they invade our feelings. The felt surfaces seduce us with their beauty, but at the same time, the organs speak to us. Unlike the mute dolls, these organs speak; tell us their story, they testify, through the voices of many different Indians and many tribes, through images of cancer infected fish and polluted landscapes. They weave a tale of betrayal, the old tale and the new tale. The tale of the nuclear industry, its assault on traditional native lands, its campaign to deposit its waste on Indian lands, its careless removal of Indians or cajoling of Indians with money. The elders speak of the illness that the nuclear industry and its invisible radioactivity causes in their tribes, birth defects, growth delays, leukemia, skin diseases, asthma, heart disease, cancer, breast, lung, colon, prostate. They reply with legends, with poetry, with a clear alternative to the stealing of the insides of the earth, they speak of their way of life, their principles of living in the land, but not gaining from it. Grand Canyon, Navaho, Hvasupai, Laguna, Acoma, Shoshone, Peyote Yakima Colville, Wishwram, Prairie Island, Apache Choctaw. Sioux. These are the tribes of the tellers of the tale.

The poet Arthur Tullee wearing a bright red shirt recites his exquisite poems of legends of death,sickness, and healing. ”

In addition to these three artists we have the wide and ongoing resistance by writers, poets, visual artists, activists and the general public to the Kinder Morgan pipeline outside of Vancouver. The link is to a poetic video by an articulate young Indigenous woman.

As of today, arrests are going on, and the destruction of protest camps is continuous. But the resistance is strong.

The Transmountain pipeline is on an existing route, but the plan is to triple its capacity. The protests have been in Burnaby outside of Vancouver BC all summer. Currently the Canadian government is looking for a buyer, since Kinder Morgan did back down and the government bought it with public funds -so much for Pierre Trudeau’s environmental credentials.

“Those arrested included 50-year-old Rita Wong, a poet and professor at Emily Carr University who organized Friday’s action on behalf of missing and murdered Indigenous women, according to a statement from Protect the Inlet, one of the many groups that oppose the Trans Mountain pipeline.

“The expansion of this pipeline would pose an increased risk to Indigenous women through displacement and man-camps, as well as everybody on Earth, through further climate destabilization,” she said in a statement, adding that “more people to make the connections between violence against the land and violence against Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women.”

“Wong was placed in what looked like a black lawn chair and carried away from the scene Friday

“Mairy Beam, Kathryn Cass and Deb Wood, who are all in their 60s, were also arrested.

“I was nervous, but also very proud to take a stand and to take a stand for Mother Earth and to stand for my granddaughters,” Beam told CTV News.”