Appropriately, a tangle of ivy hid the doorbell, but I knew I was in the right place because of the small pale red ceramic pig on the porch. As soon I entered the simple brick home of Alfredo Arreguín and Susan Lytle in North Seattle, I was immersed in a wonderland that echoed the jungles in Arreguín’s paintings. I immediately sensed the many layers of his life with Susan Lytle. Their connection flows through every surface in the house, filled with carved wooden sculpture and ceramics, rabbits, elephants, dogs, turtles, and composite beasts (those wonderful carvings from Oaxaca) arranged in careful ensembles throughout the living room and dining room.

The unity among many cultures and the universality of the creative impulse is a theme of the house and of the art created there.

First, Susan introduced me to the delicate “Queen of the Night” flower, a type of cactus that blooms for only one night with an exotic blossom. They are one subject of her paintings. (I of course immediately thought of Mozart’s Queen of the Night and her extraordinary aria, like a one night exotic blossoming itself). Nearby on a table was a Jewel Orchid, a lush jungle plant with delicate flowers.

Figure 2 Anonymous painting of a kitchen

Arreguín pointed out a long brick stove in an anonymous painting in his dining room, remarking that he fed sticks of wood into a stove like that while living with his maternal grandparents who raised him in Michoacán Mexico. His grandfather first bought Alfredo paint supplies and encouraged his art. He also took Arreguín along as a small child on a trip to Las Canoas deep in the jungle. It made a deep impression.

After his grandparents died in 1948, Arreguín moved from one family member to another, initially living with his mother, then an aunt, then his father, a boarding house, and finally another aunt. While still a teenager, as an assistant to engineers, he had a more immersive exposure in the intricacies of life in the jungle, this time in Guerrero. He would never forget that experience.

But by extraordinary serendipity he was invited to live in Seattle by a family he met when they were lost as tourists in Chapultepec park. As a result, he came to the US in January 1956. Then he was drafted into the army, and sent to Korea. Fortuitously, while serving in Asia, he was able to visit Japan. The rhythms and patterns of Japanese art as in the waves of Hokusai, for example, permeate his art to this day.

On his return, Arreguín earned two degrees at the University of Washington.

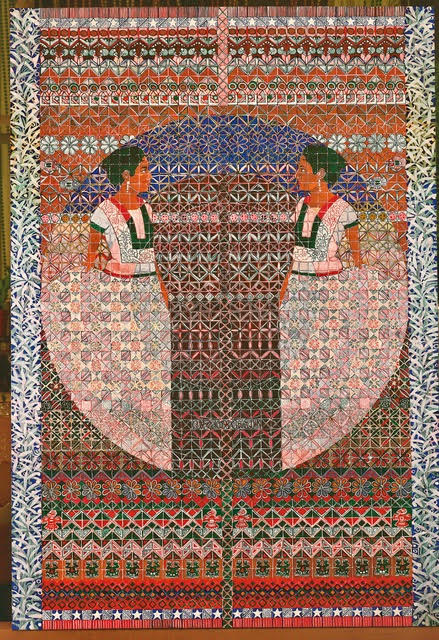

Figure 3 Alfredo Arreguín Tehuanas 1982, 64 x 43” Courtesy of the Artist

As we spoke in the dining room I was facing an early painting Tehuanas from 1982 in which two female dancers face one another, their white dresses forming two separated sides of a circle, the space between them charged with energy. The dancers, static and stately, seamlessly occupy a single flat space with a dense pattern of green, blue, red, orange, pink and lilac. These patterns and colors invoke the spirit of indigenous art in Mexico, a life long reference point for the artist.

Arreguín explained that this was an early example of his use of pattern when it took him hours to create the repeated geometric shapes.

Now, he says, it just flows from his fingers.

I was amazed when I went to the simple basement studio and saw that Arreguín and Lytle shared a single long room. There was a slight demarcation created by a pile of Alfredo’s paint tubes and Susan’s easel. Such a permeable barrier between two working artists suggests intense focus, as well secure interconnections. They met in 1974 at the Blue Moon Tavern, a longtime hangout for beat poets most famously, Jack Kerouac.

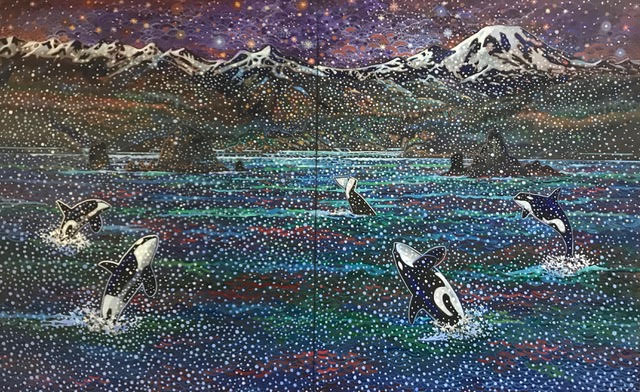

Figure 4 Alfredo Arreguín Twilight 2019 60 x 96”

On Alfredo’s easel was a large painting of leaping orcas called Twilight. As we looked at the painting he now and then added a white dot to the surface. Arreguín’s many paintings of wildlife in jungles and the sea speak to his great sense of the loss of our rich biodiversity. As he stated, “We are the most dangerous animals on the planet.” The mighty orca whale in our Southern Resident pod about which Lynda Mapes has written so eloquently in the last two years in the Seattle Times, numbers only about 73 today, and they are starving for lack of the chinook salmon they need to survive. The salmon, like the orca, are dying out, both threatened by environmental challenges from pollution to noise.

I felt deep sorrow permeating the painting, reinforced by its gentle lighting between day and night. The leaping orcas were celebrating the birth of a new baby, but I felt the threat hanging over the joy. Only last summer a baby orca born to our Southern Resident Pod died in less than an hour, and then was carried for 17 days by its mother in a tragic epic journey. This summer we have heard that the Pod has left our region in desperate search for food, and three more orcas have probably died.

In the other end of the studio several of Susan Lytle’s completed paintings of the “Queen of the Night” hung on the wall, and a work in progress on her easel. Seeing these paintings at the end of my tour, fit perfectly with my introduction to the one night bloom and death of the Queen of the Night flower as I entered. Lytle carefully explores the rapid transformations and intricacies of these briefly surviving blooms in sequences of small paintings.

Figure 5 Susan Lytle Queen of the Night 2016, 30 x 24”Courtesy of the Artist

Figure 6 Susan Lytle Night Bloom 2016, 18 x 14” Courtesy of the Artist

Figure 7Alfredo Arreguín Birds of Paradise 2012 42 x 50” Courtesy of the Artist

As I left, I looked at Birds of Paradise, hung directly opposite the front door. The multicolored birds fly and perch on branches against a background suggesting a sea and sky. The composition subtly suggests the Asian influence in his works. These birds fly joyfully in counterpoint to the leaping of the huge orcas who seem weighted with sadness. Arreguín said this painting has just been purchased by 4 Culture for the Children and Family Justice Center. He wanted to bring a feeling of freedom into a dark place. Here is his narrative:

“Birds have flown the skies since time immemorial. These beautiful creatures have inspired artists for centuries, not only with their graceful flight, but also with their song and plumage. As an artist, I am no exception. I have been fascinated with these flying miracles most of my life, and they appear in my paintings as memories of my childhood, of my travels and my daily walks and communion with Nature. This painting, Birds of Paradise, is an attempt to describe my amazement and delight upon discovering these flying jewels from Indonesia and Australia. As an artist, I would never try to compete with Nature’s creations. So, in Picasso’s words, I paint the lie that makes us see the truth.”

So on this visit, I experienced Arreguín, the man, who sorrows for the loss of the connected intersecting web of life on our planet, and Arreguín, the painter, who celebrates life in all its forms.

His partner of many years, Susan Lytle introduced me to the exotic habits and intricate beauty of the “Queen of the Night.”

Together they sing a song that goes straight into the heart.