Daniel Heyman‘s two part exhibition called

“Bearing Witnes” is at Linfield College in McMinnville Oregon and the White Box of the University of Oregon gives us unimaginable suffering and inhumanity in the first show depicting men recently released from Abu Ghraib, and some salvation in the second part about a program in Philadelphia for men released from prison who are being helped to reconnect to their children and their lives.

We know about Abu Ghraib, in media sound bites, and a few images, but Daniel has been face to face with men and women who have been subjected to the most unimaginable treatment that one person can perpetrate on another. He listened as they told in simple facts what had happened to them at the hands of the people in the prison. They had been released because it was found that they had done nothing at all.

As Brian Winkenweder, art historian at Linfield College, stated in a conversation”The military machine does not work unless you are dehumanized” And he further pointed out that the people who were perpetrating the abuse were at the bottom of a huge chain of command.

It is wonderful that Heyman’s work affected Winkenweder as he is a specialist in the history of art criticism, a long way from torture in Iraq. It demonstrates the possibilities for political art that defies all restrictions. Winkenweder calls Heyman a teller of stories : I would counter with the idea that Heyman listens and records not stories, but brutal facts.

What we see, given that awareness of the monstrosity of the military machine, is that these innocent men were physically and emotionally violated in almost every way that is possible. It was lo tech, it was physical; it used feces, urine, cold water, wet floors, wet mattresses, dogs, chains, beating, stress positions, forced sex, raping of wives and daughter, raping of prisoners by both men and women, all of these acts are told by the recently released prisoners.

Heyman listened.

He wrote down what they said verbatim.

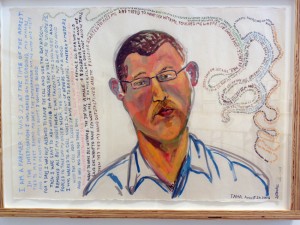

And he made portraits of the men. The gallery is a row of individual heads of men, they are dignified, and calm. It is hard to imagine surviving such abuse, but being able to at least say it must have provided some relief from the nightmare. The men are part of a class action suit against military contractors who were part of the abuse, you can’t sue the U.S. military.

In the second exhibition Heyman is listening to men who have also just come out of prison, in this case in the US. We learn not about their abuse in the prison, but the abusive circumstances of their lives, the rape of their very young mother, the murder of their very young father, their own efforts at bare survival; and then at the end we have an organization, the National Comprehensive Center for Fathers that has reached them and is offering some support.

Support for those who have been abused, who have lived at the bottom of our culture, with no resources, no opportunities. This is crucial. And Daniel in making these art works, these portrait galleries is giving us the faces and the circumstances of these individual men.

Each face is different, yellow, oranges, browns, blues, reds, and the color of face spills into changing colors of writing, the writing snakes around the head, waves in the space. The gouache colors are very strong.

Heyman listens, and the least we can do is listen also, challenging as it is to read these narratives.