During a recent residency, Mary Coss was growing barnacles on Willapa Bay, the second largest estuary in the United States (over 260 square miles!)

During a recent residency, Mary Coss was growing barnacles on Willapa Bay, the second largest estuary in the United States (over 260 square miles!)

The artist described the process to me in detail: first she coated a wire mesh with cement snags to attract the barnacles, then dragged it over an oyster bed and left it for the barnacles to forage for food. Barnacles grow very slowly so a resident scientist kept track of the barnacles growth after she left.

Then she met scientist Roger Fuller † through the “Surge” project, a pairing of scientists and artists organized through the Museum of Northwest Art by former Executive Director, Christopher Shainin.

She learned that barnacles are the “canary in the coal mine” for water salination.

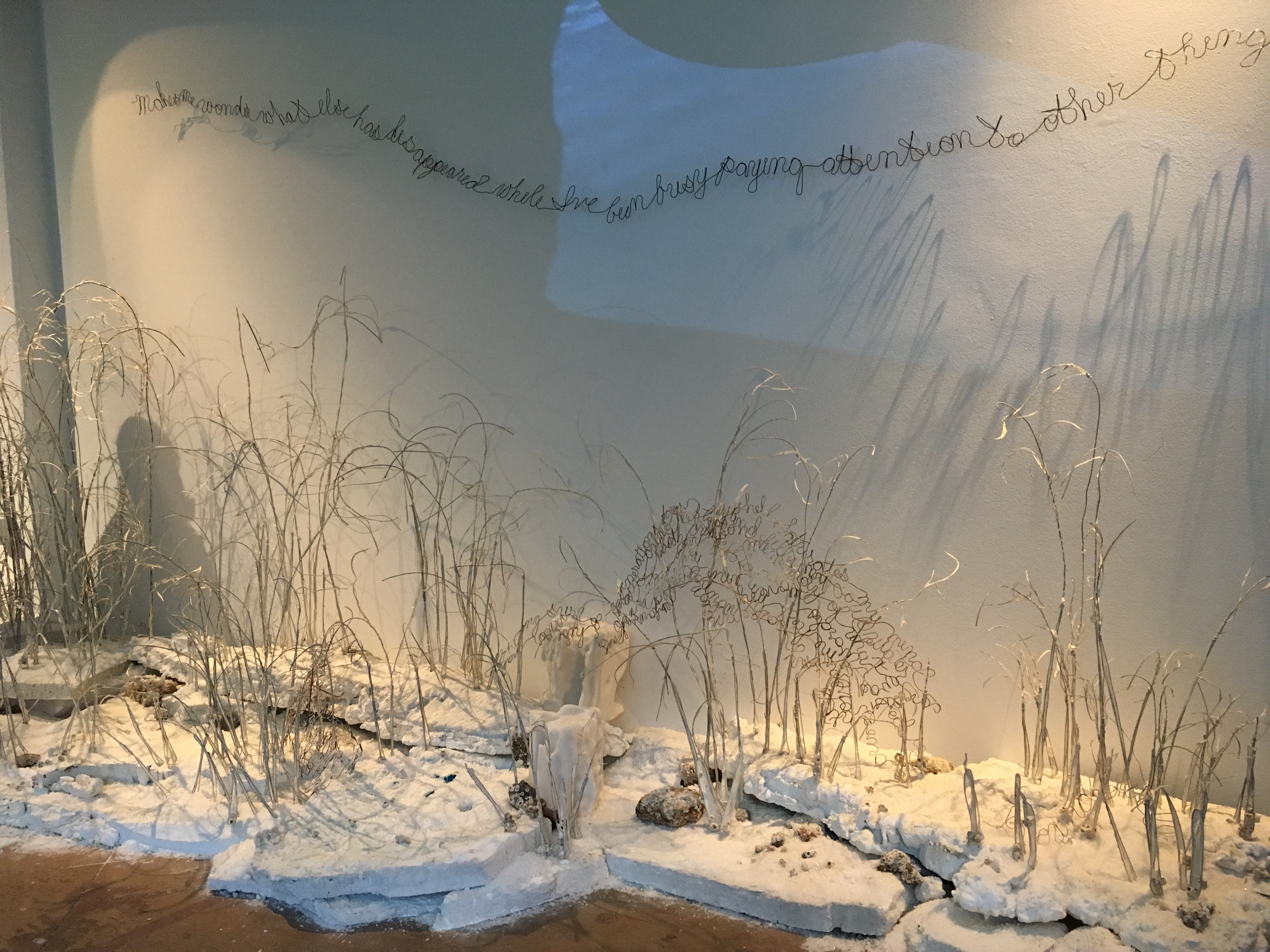

Groundswell, the last of a trilogy of works called Silent Salinity

(see her website for information on the other two), dramatically presents the first step of salination in the wild: barnacles attaching to fresh water sedge, a three sided grass.

Sedge likes freshwater and it is being starved as the fresh water rivers recede with decreasing rainfall leading to decreasing flow. This is a specific on the ground visualization of one manifestation of climate change .

Coss recreates that changing landscape in her gallery installation: the sedge is wire and paper pulp), and salt invades not only the sedge, but encroaches on us in the corners of the gallery.

Coss referred to it as a “dystopian landscape.”

Hanging above the salinated sedge you see a single line of writing in wire quoted from Roger Fuller’s essay on salination:

Silent Salinity: Net Loss

Scientist Roger Fuller’s pondering the state of the estuaries and the impact of global warming:

“I was out stomping through the mudflats in my hipwaders today, and discovered a bulrush ghost meadow. A small field of stumps, like a miniature forest clearcut. In the upper intertidal zone of brackish estuaries, tall, dense, verdant meadows of bulrushes grow, creating a tidal jungle of vegetation that hosts a myriad of critters and a far-reaching food web that spreads its strands through birds, crabs, and fish, even reaching as far as our dinner table.

But this was a ghost meadow I found, a slim reminder of a lush ecosystem once present, now vanished. Poking up from the deep, brown mud were stumps…3 inches tall, less than an inch thick, triangular, almost woody, stumps. Coated by years of mud and algae. A few sprouted barnacles. Easy to miss. Here and there a small plant poked up, but the tall, lush meadow was long gone.

There has been no meadow here for at least 8 years of my memory, and aerial photos confirm that I haven’t lost my mind, yet. I never noticed the change until today, the gradual retreat of a once lush ecosystem.

Makes me wonder what else has disappeared while I’ve been busy paying attention to other things? Perhaps that first barnacle was a sentinel of change, marking a salinity threshold silently crossed as the interplay of river and tide shifted. Or was it a shift in the food web, a small change in some quiet, unobserved corner of the complex web of life in which the bulrush is enmeshed?

It reminds me of the idea of “shifting baselines”…we think what we see today is the way it’s always been, when in fact things are slowly shifting and changing, right beneath our rubber waders. Without data, we have no sense of what we’ve lost, of what we’ve gained.

Far up the shore there is still a remnant of marsh, pinned against the dike with no place left to shift. How long will this remnant last? Will anyone notice when this meadow too slips away, when it becomes a ghost meadow?”

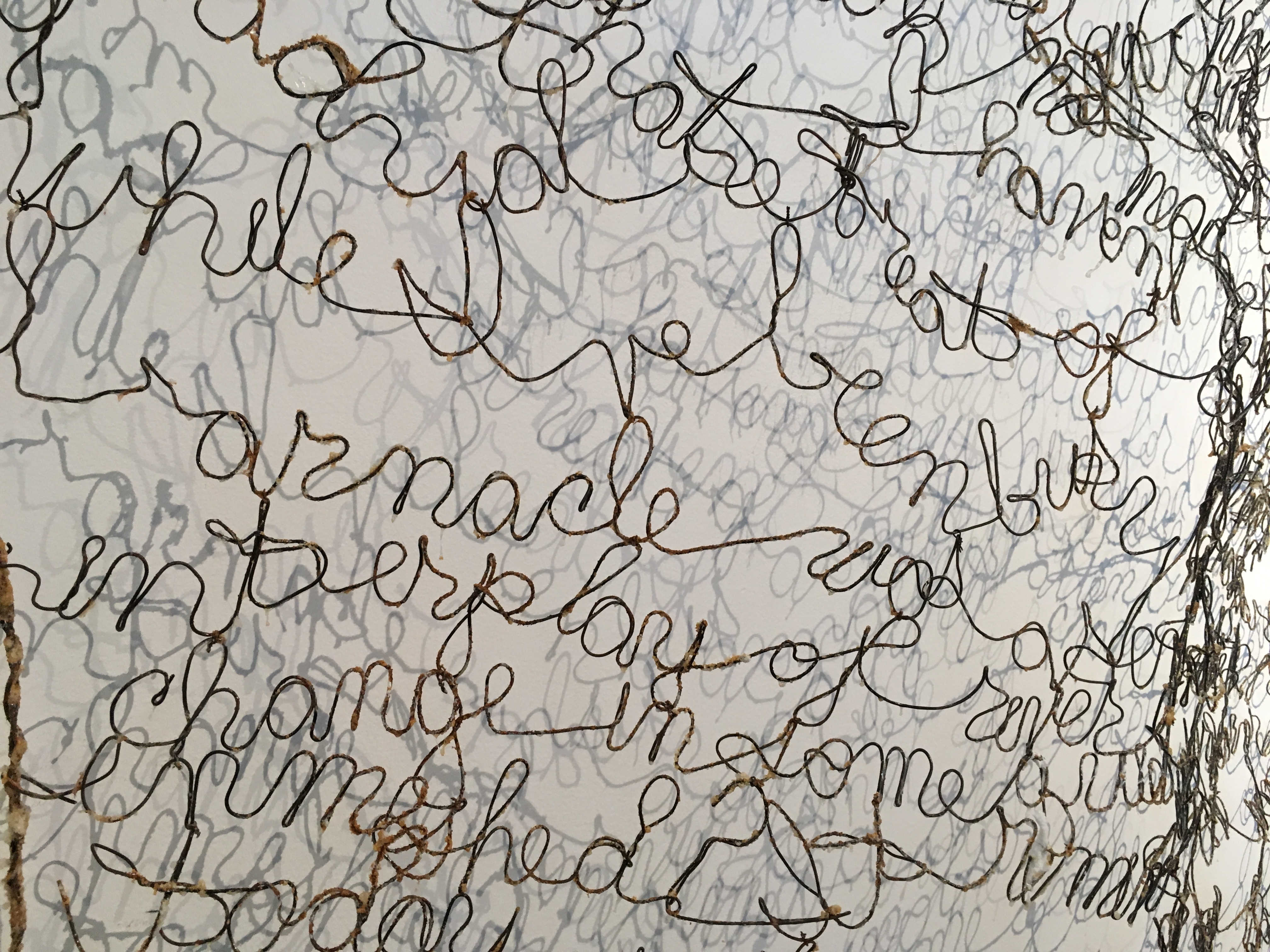

The entire poem is written in wire on the end wall. Here is a detail where you can read the word “barnacle”

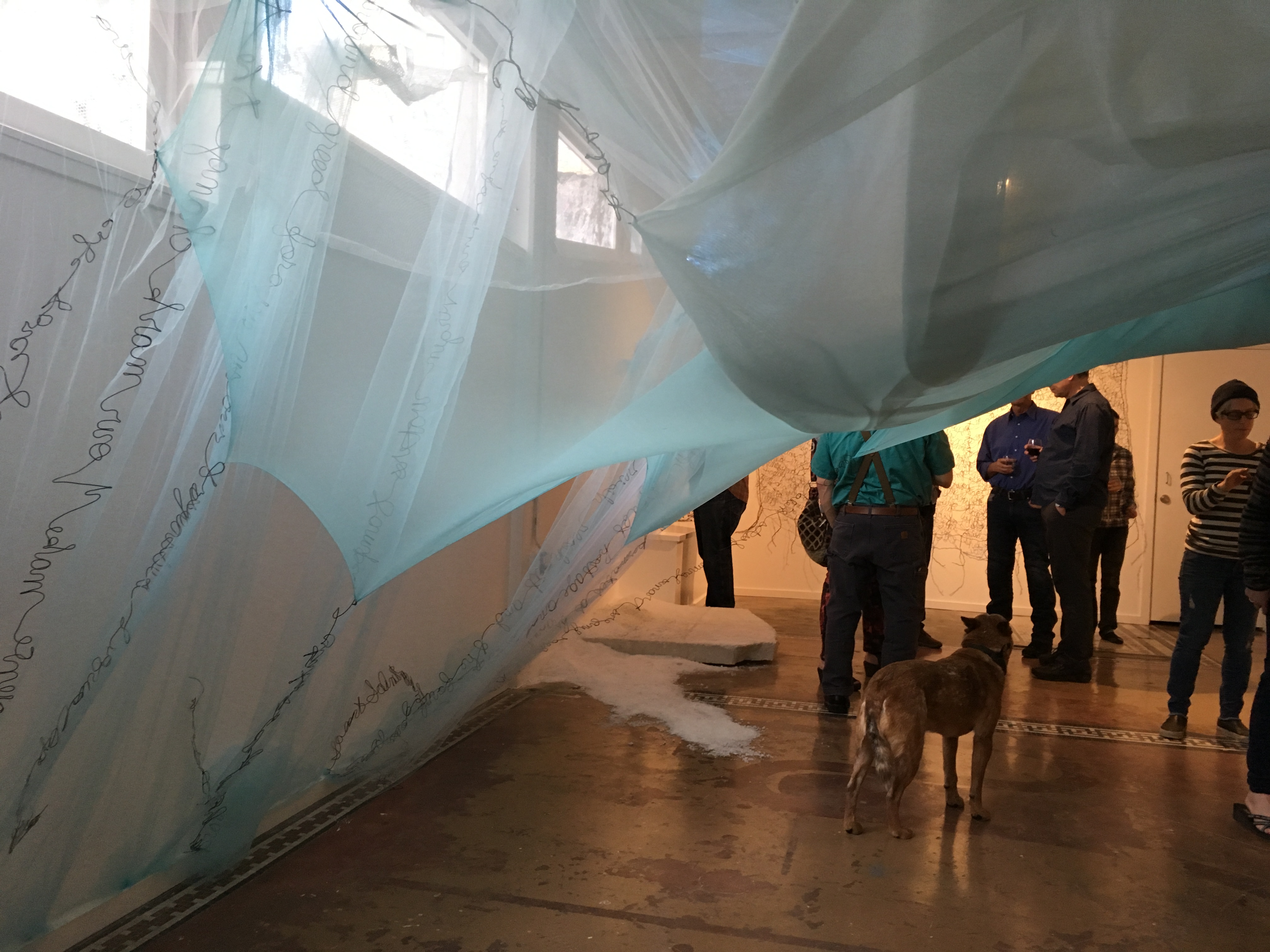

In addition to the salt encrusted sedge, and wire poetry, the installation includes a large wave which Coss described as “nature itself coming through”. The wave is manifested in a large structure of wire hung with billowing blue fabric. On it the artist projected flowing water. The wave seemed to be actually overcoming us in the gallery as it descended from the ceiling and, at the same time, the salt is spreading toward us on the floor.

The second image is the view from the window on the street. We see a salt encrusted screen and the wave. Coss inserted wire writing with her own poetry into the wave.

Coss succeeds in giving us what she calls a “visceral” reaction to climate change. The salt makes the huge story of climate change and global warming intimate. Perhaps that is because we all know salt, it is both physically part of our bodies, and a substance that we experience daily in our lives.

We also know that too little can kill us and too much, as we see in Groundswell, can also kill.

‡Scientist Roger Fuller works at the Skagit Climate Science Consortium and is a spatial ecologist with Western Washington University’s Huxley College of the Environment. He has expertise in estuarine ecology, restoration ecology, climate change impacts, climate change adaptation, and decision-support tools.

PS Read the book Salt: A World History by Mark Kurlansky to really understand how crucial salt has been historically.