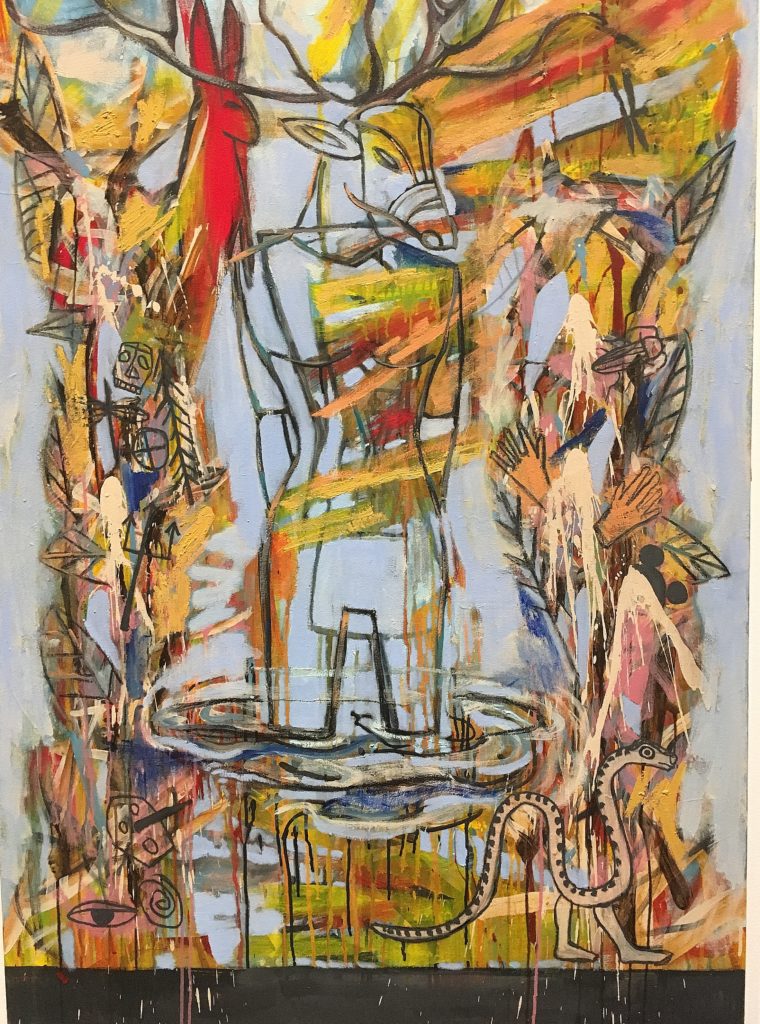

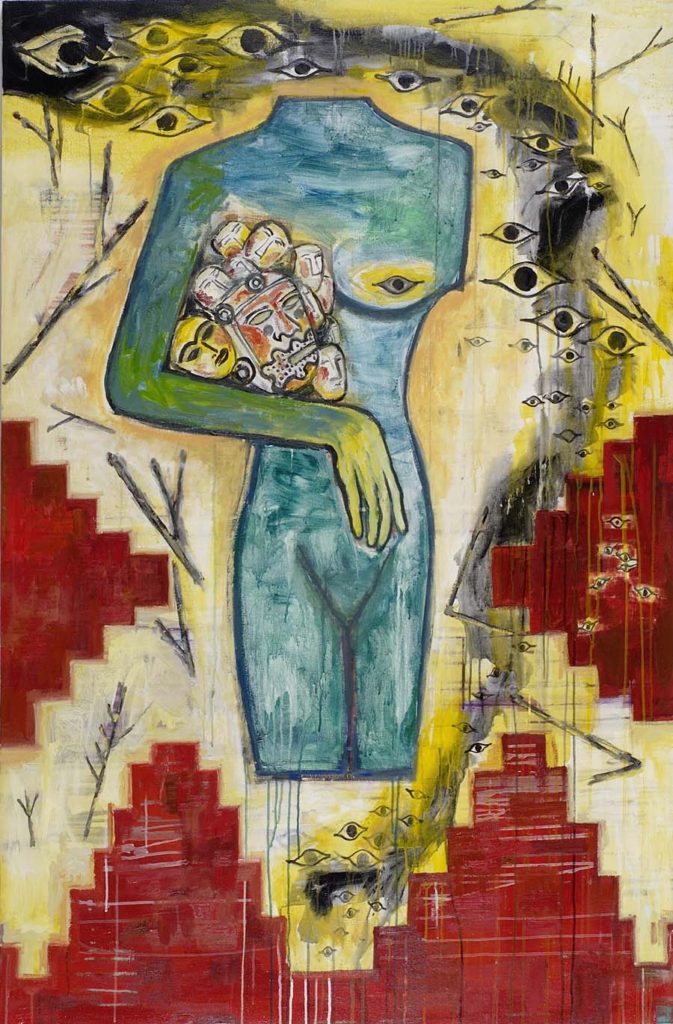

“Jaune Quick-to-See Smith In the Footsteps of my Ancestors) at the Tacoma Art Museum (until the end of June) confronts us immediately with her deep connection to the natural world and what we are doing to it as colonial extractors. The Swamp, 2015, puts the current crisis right in our face in both the styles of white modernism, and native abstractions.

The art work is described as follows: “A figure both human and animal stands in a swamp, wreathed by symbols of the vivid life one finds in swamps. Humans and animals are caught up in the stew of action, just as none escapes thoughtless decisions that poison the air and water that everyone needs. This painting acknowledges the importance of swamps within our ecosystems, their cleansing waters, and their rich habitat.”

In the central figure, Smith stated that she “created an elk anthropomorphic female figure, converted from a male elk love medicine.” As we look at it, we feel ever more deeply entangled and disoriented. The central figure is standing knee deep in a pond (a stew). The most distinct creature is a walking snake, in the lower right that seems to be walking away from the devastation. Embedded in the hot yellows and reds are fragments of masks, feathers, a pair of hands, an “Indian” stereotype profile yellow face with a single feather headdress. Oops there are the ears of Mickey Mouse ( an obvious reference to Disney, here standing in for corporate takeovers)!, In the upper left a majestic trickster rabbit ( named Nanabozho) oversees the entire disaster.

According to Gail Tremblay’s catalog essay ” “Nanabozho was sent to earth by Giche Manitou who assigned him to name all the plants and animals and to creat a system of mnemonic mark-making that would help humans remember the order of things in ceremonies and stories”

We feel the spilling of blood, the disruption of the sun, the pallid blue background indicating a vast space on which we have laid spoil to the planet. We can also see the devastation wreaked on native tribes on this continent in the last 350 years embodied in the paint strokes and the cascading images. Linear outlines suggest pictographs, but not literally, more invented, there is a Mexican mask, a bomb.

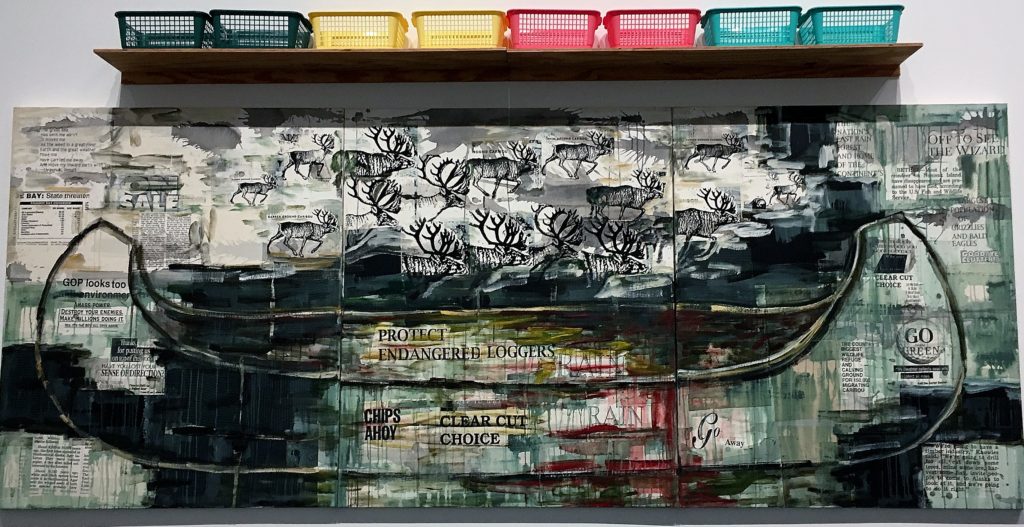

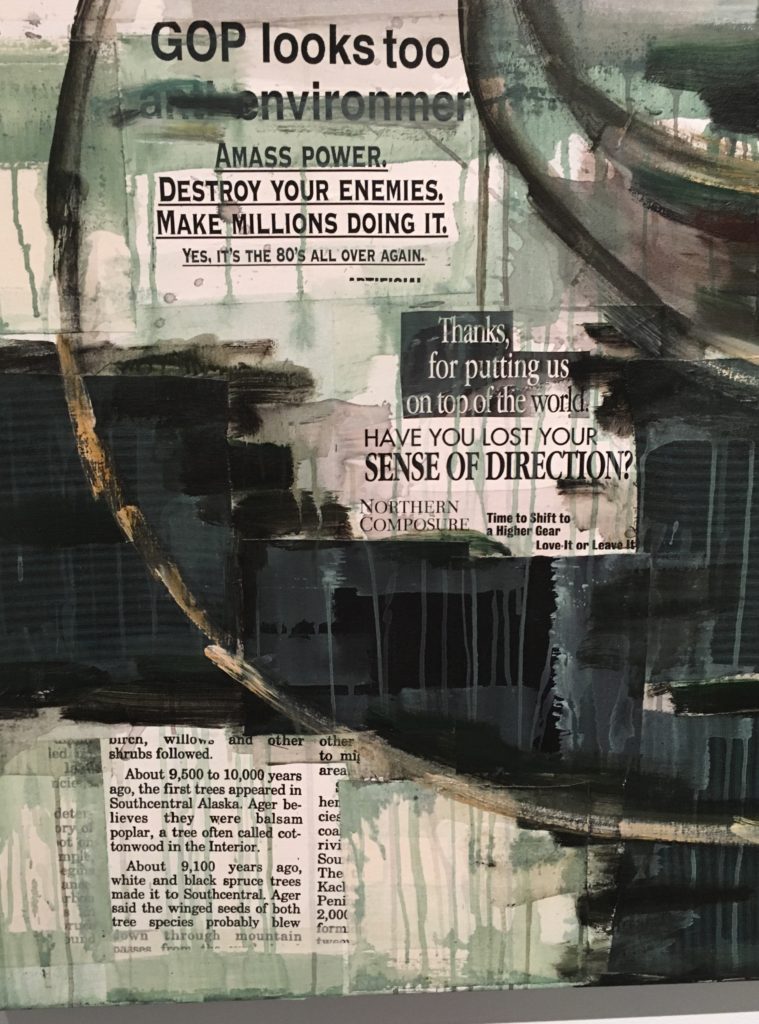

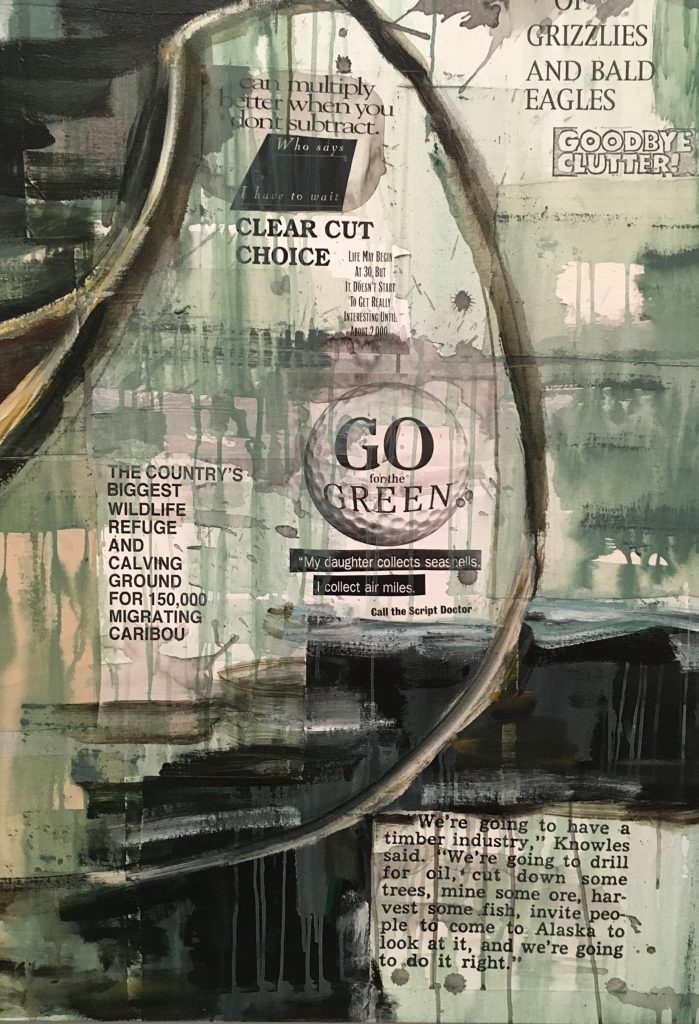

And that is only one painting! I give you Tongass Trade Canoe. This astounding ecological statement from 1996 is chillingly pertinent to our present catastrophe. It refers to the Tongass National Forest in Alaska, the calving ground of many caribou where oil is being drilled.The plastic laundry baskets suggest the trivial products that come from the destruction of the natural environment.

According to the Southeast Alaska Conservation Council “The Tongass contains nearly one-third of the old-growth temperate rain forest remaining in the world, as well as the largest tracts of old-growth forest left in the United States. Old-growth temperate rain forests hold more biomass (living stuff) per acre than any other type of ecosystem on the planet, including tropical jungles. The Tongass alone holds 8 percent of all carbon stored in U.S. national forests and is recognized as a globally significant carbon storage reserve.

” In fact, the Tongass is the last National Forest to allow large-scale clear cut logging of ancient old-growth trees, and according to draft plan released this year, will continue to permit this outdated practice for another 15 years. “

Here is a detail. Surrounding the huge canoe image are references to the devastation being wrought on the environment as a result of greed, exactly our problem today. This huge painting was completed more than 20 years ago. Its genius is the deadly ( literally) serious issue, the calving grounds of caribou, that you see marching across the top of the painting.

But it also has humor, ” Protect Endangered Loggers,” “Chips Ahoy” “Grizzlies and Bald Eagles, Goodbye Clutter” “Clear Cut Choice”

I wrote about Jaune Quick-to-See Smith in my book Art and Politics Now in the ecological chapter which addresses the huge difference of “enlightenment” attitudes to nature – that it is separate ( and inferior) from humans- and the indigenous perspective that we are part of nature. But in my book I illustrated “Fear,” also in the Tacoma exhibition, a powerful anti war work, her excruciating images of war overwhelm us with their detail and specificity.

Here is a series of four prints that bring together humor and tragedy. The US tried very hard to obliterate the native point of view, the native peoples, the native cultures of this country. Thank goodness we white people failed in that endeavor, we may have only their perspective to save us now, from our own ways.

In the movie recently screened at the Seattle Public Library, “Words from a Bear” about N. Scott Momaday, we were once again confronted with both the ongoing strength of the Native American message of our embeddedness in the land, in nature. Beside that we learned of the US efforts at genocide: slaughter of buffalo and horses,the banning of religion, especially the Sun Dance, forced marches to reservations far from familiar lands, boarding schools- the effort to make native children white by removing them at the age of four from their families; allotments which broke up tribal territories, then after World War II there was the urbanization which isolated natives again from their culture and families, on and on.

But Momaday was lucky. He did not go to a boarding school, his parents were story tellers and writers and painters and teachers, he got a full scholarship to Stanford and received a Ph.D. in 1963.In 1969 he won the Pulitzer Prize for his book House Made of Dawn. This astonished him and thrilled the entire indigenous community, as one writer declared we moved

“beyond the ethnographic past.”

The main theme of the movie though is that he “invested himself in his landscape.” He stated “I am who I am because of the land.” His voice is crucial in today’s world as we are increasingly alienated from nature. He says we cannot separate from the land. It is that insight that we all need as our culture increasingly is devolved into looking at life through a small screen filled with scarce metals taken from the earth.