Observe these two portraits

On the right is the feature image of the Metropolitan Museum of Art current exhibition of the work of Alice Neel “People Come First”

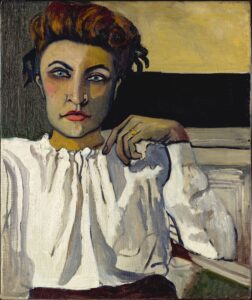

It is identified as a portrait of “Elenka”1936, about which there is no information except that she “presumably numbered among the several bohemians with whom Neel associated in Greenwich Village” Neel lived in Greenwich Village from 1931-38 . It was donated to the museum by the sons of the artist.

On the left is “Marxist Girl (Irene Peslikis) 1972 – radical feminist and crucial supporter of second generation feminism. Her pose and clothes suggest her radical position, austere colors, monochrome black, unadorned, with a confident leg slung over one arm of the chair, and a single arm raised that shows her unshaven armpit. In addition, Peslikis is famous as a founder of Redstocking Artists in 1971, she co founded the Feminist Art Journal, which also in its first issue supported Neel . The Met catalog finds it curious that the work was titled “Marxist Girl” when, as they claim she was “known at the time not as a Marxist but as a feminist.” But they also mention that she was an early member of New York’s Radical Women, a group that is avowedly Marxist and more specifically and defiantly Trotskyite. The Met catalog says RW is “feminist”. Clearly the Met wants to rush away from any Marxism in the 1970s, just as they want to avoid Communism and Socialism in the 1930s

Elenka on the other hand, wears a ruffled, white blouse, her hand dangles languidly in front of her shoulder without intention. She wears careful makeup. Her face is expressionless and mask like.

The differences are telling: in clothing, in pose, even in the yellow background, which in Elenka is pale and in Marxist Girl is intensely saturated. One woman appears to be static, the other dynamic, so although we know little about Elenka, we can tell she was not an activist from the portrait.

So why did the Met decide to put this portrait on the cover of its catalog? Perhaps because they owned it as a gift from the artists sons, but more important, because it is a mild image compared to Irene Peslikis, it deflates and defuses the radicalism of Alice Neel.

And admirable as this large exhibition is with its many categories, large, intelligent catalog, and memorable array of paintings and documents, that seems to be the overall purpose of the exhibition, to soften Neel’s extremely radical painting, perspectives and position.

Let us look at this quote near the beginning of one essay. It describes Neel as having “a stalwart sense of purpose in her dedication to an ethic of radical humanism”.

Radical humanism? Humanism is the word that these authors have latched onto, (mis)quoting Neel frequently from late interviews.

For example this is an example cited from a comment of 1950 to demonstrate her “humanism” “I have tried to assert the dignity and eternal importance of the human being.”

That of course is not the same thing as humanism!

Then they turn around her radical commitment ” Encounters with socialist and Communist activists in the United States in the late 1920s and 1930s further shaped Neel’s humanism. She joined the Communist Party in 1935 and was intermittently affiliated with the group for the rest of her life.”

To call Communism a shaping of humanism, is indeed an effort to dilute the artists deep commitment to socialism, to presenting what had been unpresented in art, the poor, the worker, the leftist leaders, and so much more.

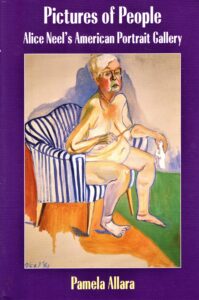

Let us contrast this effort to smooth over Neel’s politics to the ground breaking book on Alice Neel by Pamela Allara, Pictures of People, Alice Neel’s American Portrait Gallery 1998. Allara says Neel “rebelled through both an unconventional life-style and a biting wit, actions and words that indicated an absence of self censorship, a determination to disrupt polite society.”

Allara then brilliantly maps the many types of disruptions that Neel pursued.

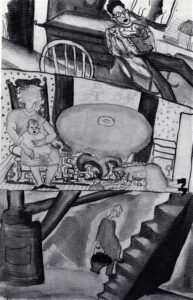

To give one example, In The Family 1927, Neel gives us the antithesis of a happy family portrait. The father slumps over in the basement as he carries coal, the mother lies almost prone on the floor as she wildly scrubs, the mother and baby ( Alice and her daughter) sit oversized in a chair, while the brother in the attic is the oblivious intellectual. Each floor suggests complete isolation. Allara compares it to the sharp descriptions in Sherwood Anderson’s small town stories, while the catalog speaks to the conflicts of motherhood and creativity which of course is not shown here.

Neel’s biggest disruptions in both her art and her life though are still to come as she lived as a single mother in poverty in the Bronx from 1938 – 1962, and in Spanish Harlem after 1962. She was on the Left from the start and stayed there.

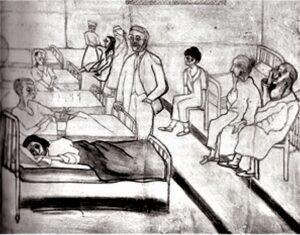

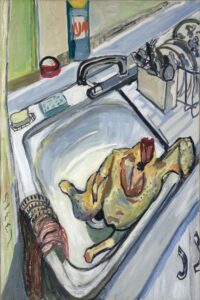

Her depictions of such subjects as “Well Baby Clinic” (left) “Suicide Ward,” (right) give us sardonic information about the failings of the public health system and social services, a subject of great importance today.

Allara’s book is mostly chronological, which makes sense with Neel as her life and her work were deeply affected by dramatic changes in the social and political climate of the 1930s, 1940s, 1950s, 1960s and 1970s.

The Met exhibition had themes ( they don’t appear in the catalog, to which I will return shortly)

Here they are

Introduction

New York City (street scenes, including demonstrations)

Home ( emphasizes her studio as her home, with intimate erotic images) Family is placed here, pretty much the antithesis of “home”

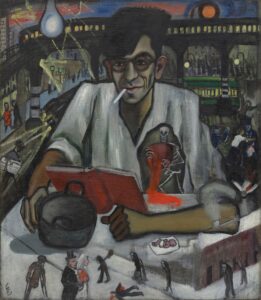

Counter/Culture ( portraits of as the label puts it “individuals who pushed social, political, and cultural boundaries, from bohemian poets and labor organizers to queer performance artists and feminist trailblazers.” So we have the radical leftist Kenneth Fearing above and the cross dressing Jackie Curtis and Rita Redd)

In other words all in one section we have every decade and many different types of people.

The Human Comedy “documenting episodes of suffering and loss, but also strength and endurance, with unsparing candor and acute empathy” The term is based on Balzac’s Human Comedy of the 19thcentury. Here is the Well Baby Clinic mentioned above.

Thanksgiving 1965 was part of Art as History. This section aligned Neel’s work with such luminaries as Robert Henri, Jacob Lawrence, and Chaim Soutine, as well Cassatt, and Van Gogh. Of course this is the most sardonic Thanksgiving image I ever saw.

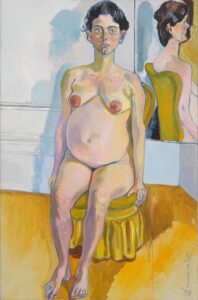

Motherhood includes images of both pregnant women, the famous image of giving birth and mother and child portraits, the term motherhood seems to me a little cozy for Neel’s cutting and incisive portraits

The Nude male and female; these two sections overlap of course and both include pregnant females. Neel’s painting included here of Andy Warhol after he was shot deserves a whole section and essay on its own!!!

Good Abstract Qualities I don’t need to elaborate on why this was here at the end. Sigh, Greenberg rears up.

In other words, these themes obscured social realism in many different places, it spread the pregnant women into three or four places. it grouped different topics together, etc.

The catalog does a better job, with excellent essays by several insightful writers (aside from the smoothing, soothing affect mentioned above). Here are the chapter headings

Anarchic Humanist, Political Creatures, Siempre en la Calle, Ill Show Everyone: An Artist Mother at Home, Painting Fruit(s), Alice Neel’s ‘Good Abstract Qualities’ based on a quote from Neel the year before she died, “I don’t think there is any great painting that doesn’t have good abstract qualities” here elevated to a major theme.

So was this major analysis by some of the best art historians now working at our most prestigious museum trying to sooth us, the audience, the museum board, the Neel family, or were these the positions of the curators and authors. It is hard to know.

At any rate, the main image on the front of the museum gives us a powerful portrait of gay men. As Randall Griffey points out, Neel died right before AIDS devastated the gay community . Several of the people she portrayed died. Griffey points out that she would not have hesitated to paint the ravages of AIDS. So this banner celebrates a moment in our country’s history, before the epidemic, as well as Neel’s own independence in representing gay men and woman throughout her career, in spite of the homophobia of the Stalinists and the Leftists surrounding her.

But unquestionably her radicalism continued throughout her life, (above is The Death of Mother Bloor, 1951 at the height of the McCarthy era, a funeral that she attended) , her feminism was deep seated way before the 1970s, and she continued to radically transform the little regarded format of a portrait until the end of her life. No better example exists than her own nude self portrait at the end of her life