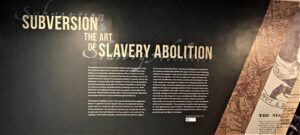

We saw this provocative exhibition “Subversion and the Art of Slavery Abolition,” at the Schomburg Library for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, when we stayed there last week.

Curated by Dr. Michelle Commander, Associate Director and Curator of the Lapidus Center for the Historical Analysis of Transatlantic Slavery, it is an astonishing work of research in the New York Public Library archives.

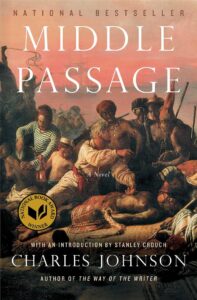

As it happens, I am immersed myself in the theme of black creativity in the US as I am reading Charles Johnson’s astonishing book

The Middle Passage, which, it seems to me, is a type of partner to Moby Dick. Johnson details the realities of a slave ship in horrifying detail with a narrator, Rutherford Calhoun, who tells all. Moby Dick of course was focused on the horrors of the whaling industry and only mentions passing slave ships in the sea. all narrated by

Ismael, a sole suvivor of the disaster.

At the same time, I am also reading a novel by Walter Moseley, brilliant writer of “gum shoe” detective stories that are much more a commentary on black life in America ( in this case 1970s ). His descriptions of many many skin colors alone is worth reading, but of course, the pervasive violence against blacks by the police is a dominating theme. Easy Rawlins is the hero, outsider, renegade private detective survivor in 12 novels by Moseley over thirty years.

On this same trip to New York City we also saw Carrie Mae Weems exhibition, about which I will write separately, as well as a contemporary artist, Leonardo Bezant

at the Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem.

at the Claire Oliver Gallery in Harlem.

incredibly intricate work with beads with several metaphorical layers.

In addition I am reading “The Matter of Black Lives” compiled by Jelani Cobb and David Remnick , New Yorker articles over decades on Black life in America.

So this exhibition at the Schomburg was extremely timely for me to see. All of the works are in the public domain on the website for the NYPL. The credit for all of them includes Photographs and Prints Division. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden, but I will only include the collection in the caption, which is an intriguing study in itself.

I am simply quoting from Dr. Commander in the text of this post. I am not able to rephrase or paraphrase her ideas. That means it is a bit long, and wordy, but worth reading. Also worth going to the website where every single one of the art works are reproduced.

(there is also an audio tour of the exhibition on the website that goes into the imagery and the topics) :

Dr. Commander introduces the exhibition with the following statement

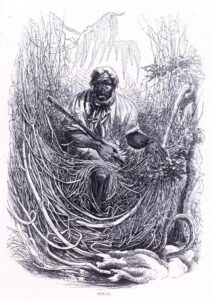

Osman the Maroon in the Swamp 1857 Slavery Collection

“Transatlantic slavery was devastatingly brutal in its utter disregard for human life. Across the Atlantic World, avaricious traders and enslavers ripped apart families and communities, callously murdering millions of people of African descent and legalizing the extraction of labor from the unwitting survivors. The United States was founded on the inalienable principles of equality, liberty, and democracy on the one hand, while the nation’s rise was enormously dependent on slavery speculation on the other. This inherent contradiction set the stage for centuries of political and philosophical conversations and unrest. While slaveholders and vigilantes threatened and attempted to control Black bodily autonomy, enslaved people and their allies artfully countered this malevolence via everyday and more formally coordinated types of resistance.

This exhibition highlights several of the ways that abolitionists engaged with the arts to agitate for enslaved people’s liberty in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Though the major focus is on American (U.S.) and British efforts, abolitionism was transnational, dynamic, and controversial.

Anti-slavery advocates immersed themselves in letter, pamphlet, and speech writing campaigns and founded newspapers, despite known and unknown dangers. Visual artists created illustrations, paintings, and photographs that featured the mundane yet absolutely reprehensible aspects of slavery to alert everyday citizens to the institution’s many horrors.

Novels, slave narratives, poetry, and music were also significant and often encoded with insurgent messages that inspired the establishment of anti-slavery societies and the formation of one of the movement’s most subversive projects: The Underground Railroad.

All of these strategies were profoundly necessary as activists rallied the public to agitate for the cause and urged governmental officials to abolish slavery. Abolitionist arts appealed to the public’s moral, religious, and political convictions, eventually yielding a robust stream of anti-slavery propaganda and radical acts that could not easily be ignored.

In 1791, the abolitionist William Wilberforce gave a speech before the British House of Commons, declaring that great responsibility came along with the awareness of slavery’s cruelty. He ended his speech with the declaration, “You may choose to look the other way but you can never again say that you did not know.” This sentiment no doubt energized and emboldened abolitionists’ incredible displays of bravery, intellect, craft, and artfulness in the fight to end slavery.”

She divided the exhibition into six themes

1 Brutality and Avarice

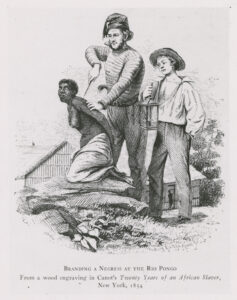

Slave Traders Branding an African Woman Creation: 1854 Slave Traders Branding an African Woman at the Rio Pongo (in Guinea, West Africa) Taken from “Captain Canot, Twenty Years of an African Slaver” Punishment and Torture Sub-Collection, Slavery Collection

“The items in this section have been selected to show the early roots of capitalist avarice/greed in the Atlantic World. The items not only highlight that slavery was seen as an everyday business in its accounting practices and uses of brutality to keep enslaved people in their places, but also gives a sense of the racist philosophies that maintained and even used the Bible to rationalize the “need” for the institution.”

2 Resistance and Rebellion

Fugitive Slave as Advertised for Capture 1857 Fugitive Slave as Advertised for Capture Fugitive Slaves Collection

“This exhibition begins with examples of enslaved people’s resistance and rebellion. Their actions– running away, fighting back on slave ships and in the Atlantic World, establishing maroon communities– most shocked and alerted the world to the injustices and inhumanity of the slave trade and slavery as it existed across the Atlantic World.

It should be noted that abolitionists argued mightily over the use of violence and force. Some felt that fighting back and being otherwise belligerent in everyday interactions would only support enslavers and other pro-slavery individuals’ arguments that slavery was beneficial because it tamed and educated so-called “primitive” people of African descent.

Smaller forms of resistance, too, were important as they kept enslavers on their toes and gave enslaved people some sense of power and control over their lives.”

3 Abolitionism

Sojourner Truth Photographer Unknown Circa 1860s

“Art denotes strategy, ingenuity, and imagination. Abolitionists of all stripes participated in the cause, prompted firstly by the refusal of African captives to abide slavery’s many violences. Enslaved people worked slowly, fought back, and set plantations aflame, giving pause to enslavers. They fellowshipped with one another and created kinship networks, despite all efforts to break their spirits and resolve to live and love. Self-liberated fugitives from slavery banded together as well as with freepersons to establish maroon, mocambo, and quilombo settlements in hills, valleys, swamps, and mountains. As instances of insurrection intensified on ships in the Middle Passage and across the Atlantic World, objections to the institution of slavery by social reformers and everyday citizens also increased, reaching fever pitch by a diversity of anti-slavery proponents in the nineteenth century.”

“Sojourner Truth (1797–1883) was born enslaved in Ulster County, New York. In 1826, she escaped the bonds of slavery with her infant daughter in tow and successfully sued to gain custody of her minor son. She later became an outspoken abolitionist and suffragist, giving the famous address known as the “Ain’t I a Woman” speech in 1851 before the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio.”

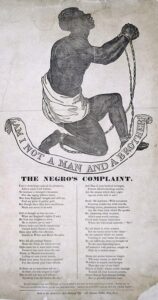

The Negros Complaint 1870 Slavery Collection

4 Poetics and Music

“Abolition-minded poetry and music got to the heart of the matter using few lyrics, generally. Poetry and musical lyrics were printed in collections as well as re-published as complements to essays and speeches in anti-slavery newspapers, almanacs, and children’s books. They were also printed and sold as broadsides at anti-slavery meetings and other events. The items in this section include those that take on the persona of enslaved individuals to address their inner turmoil and longings. Other pieces recount the everyday horrors with which the enslaved were forced to contend from the Middle Passage to the plantation.”

5 Narratives of Fugivity & Fidelity

“The items in this section include several fugitive slave narratives, anti-slavery fiction (Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin), and the ways that Black loyalty to the nation was encouraged and expressed through participation in the Civil War. Narratives of enslavement were important to the cause of abolitionism because they offered first-hand accounts of the many horrors of the institution. These narratives appealed to the sympathies of white Northern men and women, with the texts that were written by men very much reflecting on honor and manhood. Women’s narratives often delved into sentimentalism and the authors’ affective experiences as a mother and/or wife, which were feelings that women of the time, regardless of their backgrounds, might be emotionally moved by. These narratives also revealed a sense of enslaved communities’ cultures and beliefs, the restrictions that were placed upon enslaved people, the violence that undergirded slavery, as well as some of the artful ways that enslaved people resisted, banded together, and escaped their enslavement.”

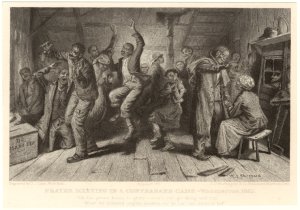

Prayer Meeting in a Contraband Camp 1887 Prayer Meeting in a Contraband Camp, Washington, 1862 William Ludwell Sheppard

“Encampments that were established near Union forces during the American Civil War by liberated enslaved people. This prayer meeting portrays its attendees worshipping charismatically. They are fellowshipping, singing, clapping, and dancing with one another perhaps in celebration or, at the very least, in hopes that liberation—worldly or heavenly—was truly to come”

6 Anti-Slavery Children’s Primers

“Abolitionists did not forget the very impressionable new generation. Within many larger publications (almanacs, newspapers, and other periodicals), there was a children’s section to help groom an abolitionist future. The Slave’s Friend is one example of a publication that was dedicated solely to children. Authors also wrote children’s books on slavery and various versions of the alphabet of slavery to appeal to children as well as to assist parents and other adults as they broached the difficult topic with youth. This section also includes an image of The New York African Free School, a critique of Harriet Beecher Stowe’s representations of Black children in her anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, and the Nautilus Life Insurance companies death ledger, containing the records of enslaved people.”

Eva and Topsy Creation: Circa 1860s Harriet Beecher Stowe Lithograph

“Eva and Topsy, major characters from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, are shown here in an affectionate pose. Throughout the novel, however, Topsy is portrayed most memorably as a naughty “pickaninny” who needs corrective whippings and consistent instruction to behave because she has no family and simply does not know better.

While some readers felt a moral dilemma about slavery as they read about Topsy’s behavioral struggles, others found that this storyline was evidence that slavery had a good overall effect on improving what they viewed as inherent Black pathology. Like many of Stowe’s other presumably well-intentioned, though exceedingly stereotypical characters, derogatory minstrel shows featured the Topsy character to poke fun at the intellect of Black people. As Stowe discovered from the backlash she received from abolitionists, literary and visual representations of Black people were and remain political.”

Each theme has detailed information sometimes tracts, sometimes books, photographs, prints. You can see them all on the website. Scroll down to the online gallery.

Seeing this exhibition at this time of so much new awareness of racism in the US both past and very much present gives us an appreciation of the huge power of resistance in creative expressions. Collectively these tracts, images, poems, songs, photographs, tell us the power of the human spirit to resist unspeakable brutality.