Michelle Kumata (right) with Cora Edmonds (left), founder of Artxchange Gallery, now ArtX Contemporary, at the beginning of Michelle’s gallery talk in her exhibition “What We Carry/ O que nós carregamos”

The story is fascinating. Kumata’s great grandmother went to Brazil in 1927 with all but two of her children. Michelle’s grandmother married and came to the US in 1918.

On the right is “Queda (Fallling)” an evocation of the experience of migration for her family in Brazil, her great grandmother is near the bottom, with other family above. They float through the air and are about to land in the lush countryside. Kumata commented that her great grandmother made this migration when she was in her mid 50s!

“This multi-generational family references the Japanese migration to Brazil: falling, blindly jumping into the unknown, with a jungle of tangled vines below. The strong vertical shape references Japanese scrolls.” ~ Michelle Kumata

They went to Brazil for work, but the agricultural work was, of course, very hard, and poorly paid and they lived in substandard sheds.

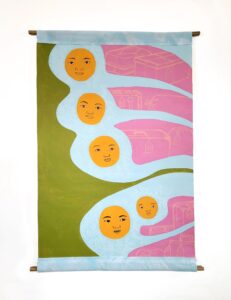

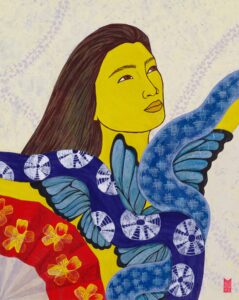

“What We Carry” on the left is described by the artist:

“When Nikkei families packed their belongings to go to camp, they were told to bring only what they could carry. A butterfly wing is patterned faces of younger generations. Outlines of suitcases represent the legacy we carry with us.” The outlines of the suitcases are barely visible in this image, in the pink area of the butterfly wings.

Crisântemo e Bananas (Chrysanthemums and Bananas)

“The chrysanthemum represents Japan. Bananas represent Brazil, farm labor, and also play on the term that some of the Asian diaspora are called, “yellow on the outside, white on the inside,” the results of assimilation. This is indicative of the complex identities of being Nikkei – being seen as the “Other” – not accepted as Brazilian enough, and also not accepted as Japanese enough.” ~ Michelle Kumata

The exhibition is probably the first time that an artist has brought together Japanese migrants’experiences in Brazil and in the US . We are familiar with our dreadful incarcerations. In Brazil the Japanese were stigmatized, but not incarcerated. They were not allowed to give their newborn children Japanese names. They were ridiculed for their food and appearance, and discriminated against in work.

(Currently, there is a reverse migration, as Brazil’s economy crumbles creating more layers of identities for the Japanese from Brazil who return to Japan. )

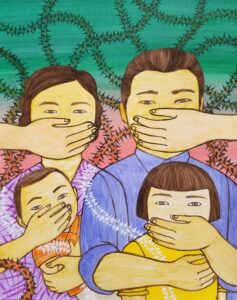

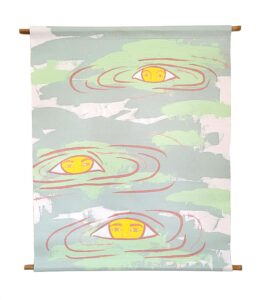

The story of Michelle’s family as seen in these beautiful art works is one of survival and endurance. The artist has carefully chosen motifs and colors to evoke various aspects of the cultural experiences in both Brazil and here. One of her themes is silence of the elder

generations, which resulted from racism and cultural oppression during World War II. Younger generations are now sharing these stories and speaking out against injustice.

This painting called “Ripples,” also refers to the enforced silence, as these floating heads have no mouths. Michelle: “This silence and the invisible scars continue to reverberate through generations.”

With support from the Meta Open Arts Program, Kumata partnered with filmmaker Tani Ikeda to create a stunning multimedia “talking mural” last year. It celebrated the stories of the Bellevue Japanese farmers who worked land that was unusable with stumps after logging, and turned it into fertile farm land. They produced much of what was sold at Pike Place Market before the incarceration.

“Emerging Radiance Honoring the Nikkei Farmers of Bellevue “ with audio narratives from 3 Bellevue farmers from the Densho archives.The archives have a huge digital library

including over 900 video oral histories about the WWII Japanese American incarceration.

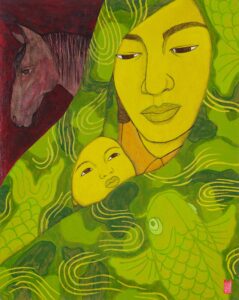

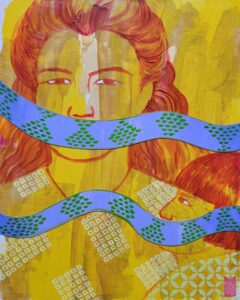

Much of this current exhibition is recent work, figurative images filled with symbolic references

We see the horse in the background as a mother holds her baby in a blanket. It makes reference to the fact that the first stop during the removal of Nikkei (Japanese diaspora) in Washington State

was the Puyallup Fair Grounds, where people of Japanese descent were forced to live in the horse stalls.

Michelle:

“Mother cradles her child, wrapped in an Army blanket in their temporary home in horse stables at the state fairgrounds. She protects her baby from the effects of war, the hatred and racism, creating a camouflage shelter covered with carp, a symbol of strength, courage, patience and perseverance.”

You can see the carp on the blanket.

Moving to Brazil:

“Alcançar (Reach)” has a carefully chosen selection of patterns, each with specific meaning:

Michelle:

“The woman raises her arms, building strength from snakes and butterflies, as the brilliant blossoms of the Pau Brasil, the national tree of Brazil, dance on the folded fan. The shadows of crown of thorns branches fade behind.

What does it mean to be Japanese Brazilian? How does one navigate their own heritage, ethnicity and claim their own identity?”

The color of her face is intentional. We see a woman looking into the distance, buoyed up by the snakes and butterflies. It is a positive image, her expression is one of perseverence and hope.

Kumata paints with specifically chosen imagery in brilliant color so her artwork becomes a celebration at the same time that it is honoring the difficulties these people experienced.

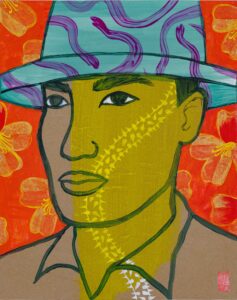

Again we see thorns here in “Espinos (Thorns).”

“The Nikkeijin may be culturally, ethnically and linguistically Brazilian, but very often they are seen as ‘false nationals.’ With the economic success of Japan, the image has altered, but the Nikkeijin are still presented in the Brazilian media as ‘foreigners’ and not as Brazilians.” ~ From “Migrants and Identity in Japan and Brazil: The Nikkeijin” Daniela de Carvalho, 2003, p. 65

You might miss the meaning here without looking carefully. The color of the face is intentionally two toned, divided. Thorns pass over his face, and snakes fill his hat, but in the background we see a celebratory red and orange filled with butterflies.

In “Cobras (Snakes),” 2021, the woman and child are silenced by the snakes, slithering across the foreground. This is again, the idea of silence.

From “Migrants and Identity in Japan and Brazil: The Nikkeijin.” Daniela de Carvalho

“Not being Japanese was particularly important, and although almost all Nisei had attended Nihongakko (Japanese language school), they did their best to forget what they had learned or to pretend they had never learned Japanese. It was believed that despite physical differences, not speaking Japanese and knowing little about Japanese culture would mean being identified (and accepted) as entirely Brazilian.”

This exhibition glows with color and pattern even as it gives us a history we know so little about in Brazil, and a new perspective on the incarceration experience here.

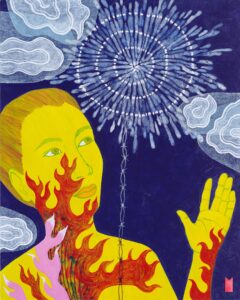

“Healing,” represents survival:

“Barbed wire flows from the heart, releasing a brilliant shibori firework. The verb “shiboru” means to wring, squeeze and press.” Fabric is twisted, folded, stitched and dyed in this intricate technique, resulting in beautiful, unexpected patterns. Hope flows as we find ways to heal.” ~ Michelle Kumata