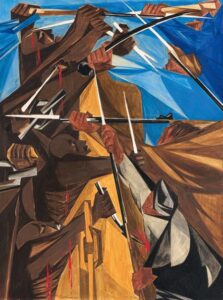

Looking at this single image of the Boston Tea Party the no 3 panel in Jacob Lawrence’s “Struggle: From The History of the American People” we see how radical Lawrence is in every respect: composition, space, color, subject matter. In stark contrast to his well-known “Migration” series, the work from “Struggle” includes dynamic thrusting diagonals and horizontals that shoot across the picture plane, in this case a shallow space. The colors are also striking: neither realistic, pretty or even believable, they tell us of conflict, red, green, of harsh confrontation. The fragmented robes, recalling cubism in the fractured surfaces, also speak of conflict. Nothing in Lawrence’s work is a formal device used for its own sake. Looking more closely we see huge brown hands grabbing the heads of three “Indians.”

All of this in a small panel measuring 12 x 16″.

The caption reads: “Rally Mohawks! Bring out your axes and tell King George we’ll pay no taxes on his foreign tea.” First, although it was a non violent protest, Lawrence reinterprets it as an intense struggle with axes and fists. the caption is from a 1773 protest song. based on the “tea party.”

The so called Sons of Liberty (perhaps a group called that now?) dressed as Mohawk Indians (!) see above, and dumped hundreds of pounds of tea into Boston Harbor. The tea was from the East India company, so also the product of colonization. Dressed as Mohawks meant the Indians could be blamed, and the actual participants melted into the community.

The exhibition of Lawrence’s “Struggle “series couldn’t have been better timed at the Seattle Art Museum. We saw it not long after the January 6 insurrection in the Capital which attempted to overthrow the election and throw the government into turmoil.

That recent struggle invoked the terms of our early struggle for independence from Britain, militia, patriots, minutemen, and it too was motivated by economics. You may recall that the so-called Boston tea party was because Britain wanted to impose “taxation without representation.” Britain wanted to be paid back for helping the colonists during the French and Indian wars. But of course the colonists, like all groups that seek independence, wanted to keep their money and spend it the way they wanted to. They didn’t want anyone taking away their money ( or in our recent case, “their” election)

The rethinking of history in this series begins with Panel no 1 of Patrick Henry. In this incredible image of Henry reaches a long hand over a crowd he roused with equally long arms, saying ” is life so dear or peace so sweet as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery? ( 1773)

Henry is better known for his “Give me Liberty or Give me Death” (from the same 1773 speech). By choosing this quote Lawrence immediately reframes the image and the speech as a collective struggle, not that of one person, the energy of the arcing hand seems to radiate toward the crowd, but in the dark sky are drops of blood.

Almost every image in “Struggle” has drops of blood, wounded men, wounded horses, or as here, the sky rains blood.

The struggle is never peaceful. Only death and defeat are quiet.

One of the most poignant images is

number 5 with the caption “We have no property! We have no wives! No children, We have no city! no country!” from a petition of many slaves 1773. This outcry before the revolution underscores that “liberty” is only for the elite few.

It reminds us of the cruelty of slavery in, among many cruelties, breaking apart families (much as the previous President did to immigrants).

Jacob Lawrence started thinking about the theme of Struggle in 1949. He pursued research for five years and started painting in 1954 perhaps not coincidentally just as the high pitch of the McCarthy era was winding down. He planned it as McCarthy was accusing hundreds of Americans of being communist, ruining their careers and their lives. He began to paint in the same year as the Brown vs Board of Education decision , in May, and continued to paint as Emmett Till was lynched in August 1955 and Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat in December 1955 and Martin Luther King leads a bus boycott .

He spoke of the series as a history of “all the peoples who emigrated to the “New World.” By transforming it conceptually from his first idea of the history of the Negro people to that of all those who contributed to building the United States, he wanted to show a “constant search for the perfect society.”

This newly recovered image of Immigration (Panel 28) has the caption “Immigrants admitted from all countries: 1820 – 1840- 115,773”

Again, how timely. This is an early era of migration before any restrictive laws began. The first “Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and Alien Contract Labor laws of 1885 and 1887 prohibited certain laborers from immigrating to the United States.” These laws were aimed directly at Chinese laborers building the railroad to prevent them from bringing their families. As those of us who live in the west know well, Chinese laborers were forcibly expelled from towns all over the West.

Lawrence brilliantly rethought the history of America, taking familiar events like the “ride of Paul Revere” and re interpreting them, as well as elevating events we may not have known about.

For example

here is another panel (no 16) recovered as a result of the exhibition with a label that sounds like a comment from last January

“there are combustibles in every State which a spark might set fire to – Washington 26 December 1786”. Here we see a confrontation between farmers ( in brownish, green and yellow ) and the federal government (in blue), perhaps the Shays rebellion, in which impoverished farmers and veterans protested taxes on them to pay for war debt. Again money, again echoes of today.

One favorite of mine is no 18

This is an image of Sacajawea ( in red) reuniting with her brother (in blue). Sacajewea had been kidnapped from her tribe the Lemhi Shoshone and enslaved as a child. Here she meets her brother who is chief of the Lemhi Shosone, an emotional reunion recorded in

the journals of Lewis and Clark.

This image (no 21)also addresses Natives with the caption quoting from the famous Shawnee Chief Tecumseh ” Listen, Father! The American have not yet defeated us by land; neither are we sure they have done so by water – we therefore wish to remain here and fight our enemy”(to the British, 1811)

Tecumseh lost, and is memorialized as a dead chief in a marble sculpture in Washington’s Smithsonian Museum of American Art, but here we have the background to the ending, the moment of courage, with again the thrusting diagonals in the foreground of American soldiers in blue set against the Native fighters.

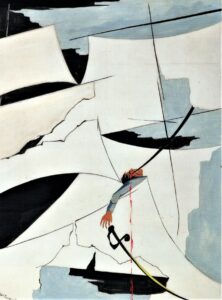

And here (panel 23)a moment of defeat in the war of 1812 against the British:

“….If we fail let us fail like men, and expire together in one common struggle,….” Henry Clay 1813 this is during the fight with the British on Lake Erie. The image focuses on just one dead soldier amidst a sea of abstracted white sails, even as the quote speaks of the collective.

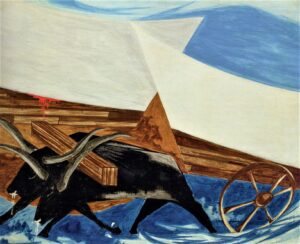

Finally, one more image, the final image in the series

“Old America seems to be breaking up and moving Westward,”

We see not the cliche pioneers in their wagons, but a pair of overburdened oxen dragging a wagon.

Lawrence throughout the series focuses on the courage, the suffering, and the contradiction of accepted history and the reality of the conflicts.

In addition, working at the height of Abstract Expressionism in art, he transformed his own art into a dynamic, energized imagery, which he alternated with static works. Although the installation of the series with individually matted and framed works and large captions, breaks up the larger experience of rhythmic subtleties that move from one panel to the next, that is one aspect of his work, an almost musical tempo. (This insight came to me from Diane Tepfer, an art historian who helped install the Migration Series in Washington DC).

So Lawrence took abstract expressionism, also a response to McCarthy that cleansed art of figuration and political content, and reinterpreted it with dynamic figures and confrontational content.

Each image in the series gives us struggles, of Native Americans, of slaves, of working class whites, of soldiers, of farmers, of immigrants.

Although he planned to have sixty panels, he stopped working on it in 1955 for various reasons.

But he continued to address struggle in later works that make direct references to the Civil Rights Struggle. I wish we had the other thirty works. Ending with the beginnings of the Movement West is tantalizing, when we think of the struggles to come next, more forcible displacement of Native Americans, struggles over slavery, the Civil War, the transcontinental railroad built by Chinese labor, the “Red Scare”, the Depression, the New Deal, the Japanese incarceration during World War II, and on and on.

***

I have taken the rare opportunity to see this exhibition four times, and still have not absorbed all of its insights. Lawrence is making a radical statement as a testament to the foundations of our country in bloodshed, conflict, betrayals, and suffering.

It is also an homage to all of the courageous ordinary people who survived.