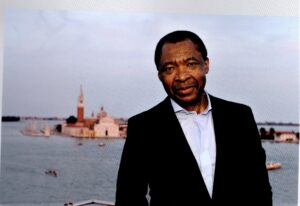

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” ( New Museum February 17 – June 6, 2021) honors the brilliant Nigerian curator Okwui Enwezor. Conceived and partially planned before his death in March 2019, the exhibition was realized by a team of curators at the New Museum.

The theme has only become more potent since the fall of 2018 when Enwezor was first invited to create the exhibition.

”Grieve and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” features thirty-seven artists from established to emerging presenting intensely confrontational works that expand the idea of grief in many directions. The partner concept, white grievance, emerges mainly in the catalog essays.

As stated in the press release the exhibition “brings together works that Address Black Grief as a National Emergency in the Face of a Politically Orchestrated White Grievance.”

“White Grievance” is a concept that we can think about. Enwezor starts from the perspective of the Gettysburg address by Abraham Lincoln. Gettysburg is the site of a major defeat of the Confederate army let by Robert E. Lee (July 1-3, 1863) that led to the victory of the Union in the Civil War. Enwezor quotes the entire address in his forward characterizing it as “terse and succinct” in stating “that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom “

But Gettysburg and the defeat of the Confederacy also set the stage for white grievance, giving birth to white supremacy and the Ku Klux Klan. Trump held a rally there in October 2016 which Enwezor describes as “a surreptitious attempt to obscure and blur Lincoln’s statement and shape a completely new narrative of American purpose. . . . part of a carefully crafted strategy appealing to white grievance as part of his larger, divisive and white nationalist ideology.”

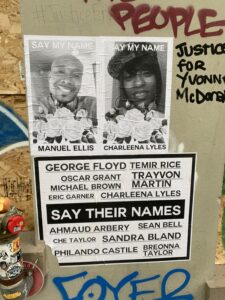

This clear analysis is further developed in all the catalog essays. First Judith Butler’s “Between Grief and Grievance, a New Sense of Justice,” lays out the gap between loss and the “appeal to repair and rectify that loss.” Butler speaks of the role of photography as a trophy rather than a proof of guilt in a crime. Enwezor refers to it as the “vampiric machine” in reference to pictures of starving children for example.

We have witnessed this year and in many recent years how photography has been used to commemorate and to protest: how it is cropped and edited can condemn or condone guilt, even as it irrefutably shows the facts.

Butler also addresses the difference of grievance for people of color and for white supremacists. For the person of color who is in danger, going to the law can lead to your own murder. The burden of the dangers of functioning without the protection of the law becomes an unbearable constant weight for people of color. That theme is also in Claudia Rankin’s essay “The Condition of Black Life is One of Mourning.”

In contrast, as evidenced in the present moment, white grievance declares, as Butler puts it,

“loss of presumptive supremacy discounting the petition to justice in favor of its own challenged sense of power. “

That challenged sense of power, Enwezor argues, has its roots in the Southern defeat in the Civil War.

Since Trump cultivated it at his rally at the site of the Gettysburg loss, it has metastasized all over the country most spectacularly on January 6, 2021. Armed resistance by militias in many states have attacked the capitols of several states, and currently there are widespread efforts to severely limit access to voting for people of color and the working class.

Juliet Hooker suggests in “White Grievance and the Problem of Political Loss,” that Trump’s strategy is “driven by a specific form of racial nostalgia that magnifies symbolic black gains into occasions of white dislocation and displacement.” The result is that when white privilege is in crisis because white dominance is threatened, many white citizens not only are unable or unwilling to recognize black suffering: they mobilize a sense of white victimhood in response.”

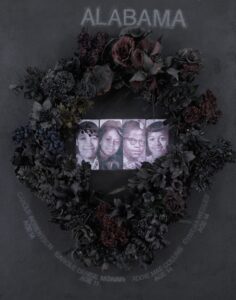

Howardena Pindell Four Little Girls Killed, 2020 mixed media on canvas, Courtesy the artist, Garth Greenan Gallery, and Victoria Miro Gallery.

detail of Four Little Girls Killed

Hooker points out that massive black losses lead to small symbolic losses for whites. So after the murder of eight people at a prayer meeting, the removal of a confederate flag followed.

This huge imbalance continues to the present: “As whites mourn their lost privileges, blacks mourn their dead. “

Boy on the left “Why do you see me as a crime?” and on the right “All Mothers were summoned when George called for his”

Hooker’s essay was published in 2017, long before the great outpouring in response to the irrefutably documented murder of George Floyd murder, yet her words are entirely accurate:

“Racial politics today seem headed for an intractable impasse. On the one hand there is highly visible black and nonwhite grief driven by acts of violence carried out by police and radicalized white supremacists targeting various racial minorities, as well as cruel state polities aimed at immigrants,Muslims and others. Meanwhile there is a large cross section of whites mobilized by a deeply felt sense of grievance and racial resentment. “

Ta Nahisi Coates ”The First White President” doubles down on white supremacism and Trump who “has made the awful inheritance explicit . . . To Trump white is neither notional nor symbolic but is the very core of his power”

But Coates goes much further than that. He speaks of the “bloody heirloom,” the inheritance of white privilege from the founding of the nation.

Then he points out how liberal politicians and journalists separate themselves from the white working class, and point to them as the Trump supporters. When in fact, Coates states, whites from all economic levels supported Trump. The myth of white anti racism is exploded by Coates and he implicates whites in enabling the election of an overtly racist white man. Furthermore, in demonstrating that a demagogue can create havoc without punishment, the Trump example is dangerous (as we are seeing everyday).

But in the end, Coates declares that “there can be no conflict between the naming of whiteness and the naming of the degradation brought about by an unrestrained capitalism, by the privileging of greed and the legal encouragement to hoarding and more elegant plunder. . . . I see the fight against sexism, racism, poverty and even war finding their union not in synonymity but in their ultimate goal – a world more humane. “

These powerful essays together with those of many others in the catalog, constitute the articulate indictment of white privilege as the foundation of white grievance and where we are today.

At the same time that this catalog went to press in 2020, Isabel Wilkerson’s book Caste, exploded on the scene, tracing white supremacy back to the very first arrivals of Africans in the early 17th century. No Europeans called themselves white until they arrived in America, where white became a racial invention to distinguish from black slaves. Being white became the privileged caste from the beginning. It is the threat to that privilege that motivates white grievance today.

Let us turn to the exhibition itself, which is entirely the work of African American artists of all ages. All of them address grief, but in many ways.

The exhibition centers around several anchor works ( as cited in the catalog, although that is not evident in the installation and other works are equally important)

Jean Michel Basquiat’s Procession

Nari Ward’s Peace Keeper,

Daniel La Rue Johnson, Freedom Now Number 1,

April 13 ,1963 -January 14,1964 includes a broken mouse trap, a fexible tube, and a FREEDOM now button, from the Congress on Racial Equality. collected as he travelled through the South “these objects are traditionally used for trapping, cutting and hacking, functions that suggest dismemberment and fracture ” ( catalog p 249)

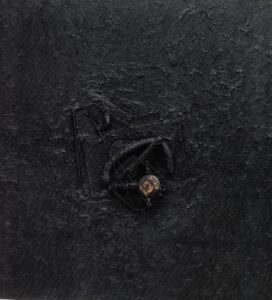

Jack Whitten’s Birmingham, 1964 (to which I return at the end of the post), aluminum foil, newsprint, stocking and oil on plywood

Ward’s Peace Keeper originally created for the 1995 Whitney Biennial, and re created for this exhibition, deeply inspired Enwezor, according to Massimilliano Gioni.

A giant memorial in the form of a hearse covered in tar and peacock feathers inside a cage, the metaphors are unmistakable.

Mufflers hang in a cloud above it, and rusted metal pipes surround it on the floor, the whole imprisoned in a cage.

Enwezor called it a “tour de force” melding of materiality and spirituality, a combination that Enwezor saw as central to discussion around mourning in African American culture” (paraphrased by Massimilano Gioni). He planned to give a series of lectures on the intersection of black mourning and white nationalism, a crucial concept that has escalated dramatically in the last two years.

Thinking about the rapidly evolving role of photography in the documentation of black death, the photographers included in “Grief and Grievance” offer a nuanced expansion of the public media’s narrow focus on murder and grief.

La Toya Ruby Frazier speaking in her exhibition at the Seattle Art Museum

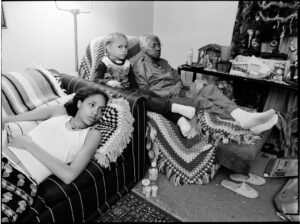

LaToya Ruby Frazier descends from generations of her family who lived and worked in Braddock Pennsylvania, the home of Andrew Carnegie’s first and last steel mill. LaToya‘s grandmother, who raised her, was born in the 1940s when the town was prosperous; her mother in the 1960s, the era of Reagonomics; and she herself in the 1980s, when the war on drugs decimated her family.

LaToya’s series “The Notion of Family” (2001-2014 above) intimately offers us both the love she experienced, and the illness both she her family suffer as a result of toxins in the air and water near the steel plant.

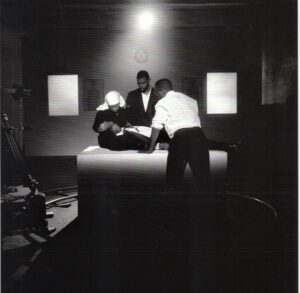

Carrie Mae Weems series “Constructing History” stages famous Civil Rights events with art students. She calls attention to the generic media perceptions of these moments of intense grief and resistance by themes “The Assassination of Medgar, Malcolm and Martin” above or the “Endless Weeping of Women” Clearly contrived images, as is the public understanding of the depth of the feelings that permeated the events, Weems give us grieving as a construct, to underscore how little it is understood.

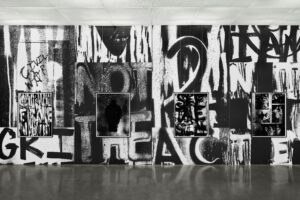

The ground floor of the museum provides intense juxtapositions of media and content that begin the immersion in both grief and resistance throughout the exhibition. Adam Pendleton covered lobby walls in graffiti-like writing that screams at us in messages repeated over and over. “As Heavy as Sculpture” includes words like ACAB (all cops are bastards) and other words taken from protests, combined with his own slogans and photographs of masks and figures to suggest the fragmentation of visual and verbal communications in protests that becomes a type of street poetry.

Also on the entrance floor is Arthur Jafa’s Love is the Message, the Message is Death first launched in 2016-17 ( detail above) as an extraordinary seven minute homage to black life. Created in rapid jump cuts from many sources, it jolts us between the joy and nightmare of being black in the U.S, set to Kanye West’s gospel “Ultralight Beam.”

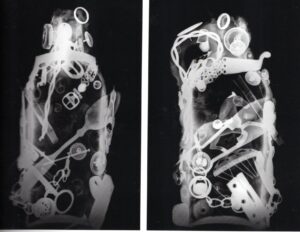

Not far away is musician Terry Adkins’ hugely enlarged xrays of memory jugs, vessels with personal mementos such as rings, watches, jacks, and spoons attached to their outside. Originally physical grave markers, these looming photographs now embody both the ghosts of the original owner of the objects, the ghosts of a long-gone life and ritual, and the ghosts of our contemporary world.

In the same gallery an actual cattle squeeze painted black The Full Severity of Compassion, by Tiona Nekkia McClodden presents its horrifying function, to squeeze cattle before they are killed, like a satanic hug. The psychic and physical immediacy of the squeeze cannot be avoided, even as we recognize a metaphoric level that refers to black lives.

On the second floor, in addition to Ward’s overwhelming sculpture, we see the work of Sabie Else Smith, tiny polaroids immersed in black grounds referring to the photos visitors make of their family members when they visit them in prison.

A video on the ground floor Alone by Garrett Bradley also speaks to the same subject, expanding the experience of visiting a prison to a deeply moving narrative of the life of a young woman left alone, separated from her beloved fiance.

Dawoud Bey’s large paired black and white portraits from his Birmingham Project, 2012 presents one young person at the age of the the four young girls killed in the bombing of the 16th st Baptist Church, and two young men killed in protests that followed. The second image is an adult of the age these young people would be were they still alive. Instead of a one dimensional victim, Bey presents people who are looking straight at us, alive and strong, at the same time that we see the deep pain inside the bodies of both young and old.

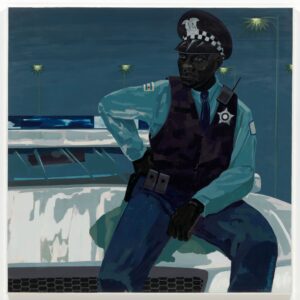

Moving to the third floor, where Basquiat’s Procession, a reference to a jazz funeral, greets us first, then a room full of Kerry James Marshall’s layered collage/paintings that honor the dead. His untitled (policeman), of a black policeman speaks of the contradictions at the heart of survival for black people. Here is a securely employed middle class black man, who is part of an oppressive state sanctioned system. His posture with one hand on his hip, the other on his knee as well as his gaze away from us into the middle distance, as though he sees his own death there, suggest his own fears as well as his professionalism.

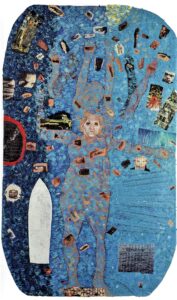

Near the stairwell to the fourth floor is Howardena Pindell’s 1988 Autobiography, Water(Ancestors/Middle Passage/Family Ghosts which I consider one of the benchmark historical works although it wasn’t cited in the catalog. It looms above us with a life size figure multiple arms flailing in water filled with the eyes and heads and hands of so many others. Beside the figure Pindell quotes a document that states that a black man who intervenes when a white man is raping his wife will be killed.

Hank Willis Thomas’s 14,719, hangs in the stairwell –long blue banners covered in stars, each one representing a death by gunshot in 2018. The sudden switch in meaning from an American flag so often used in commemoration of death, here to speak of an almost invisible slaughter, turns a memorial into a scream.

Of course it is impossible for me to write about all the work in the exhibition, much as I would like to enumerate every one. What is striking is the synergy among the works, each speaks to the other, in a continuous narrative. At the same time, these artists all speak of survival, resistance, and defiance. Black grievance emerges as the larger arc of the exhibition, as these works speak out against injustice, invisibility, and the incomprehensible.

“Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America” pays fitting tribute to Okwui Enwezor. It also stands as a celebration of black creativity and the power artists have to make a stand against the staggering racial injustices of this country.

Writing this on the Fourth of July, I can’t help mention the irony of the celebration of independence that was for white men only: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.—”

By 1776 over 67,000 Africans already had been brought to the US, the first declared to be a slave rather than an indentured servant in 1654 ( the total would rise to 305,000 by 1876). Apparently Jefferson called for an end to the importing of Africans for slavery in his first draft of the Declaration of Independence: “ He(King George) has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither.”

It was removed in deference to the many business men benefitting from slaves.

I conclude with this early work of Jack Whitten, Birmingham 1964 with a photo of police brutality appearing behind peeling aluminum foil a reference to the town Bessemer Alabama, the town where Whitten grew up. The artist left the South shortly after he made this work to have a dazzling career in New York City.

Out of this darkness came light, as I talk about in my review of his show at the Met Breuer in 2018

Let us hope that continues to be the case for this country. Out of our darkness can still come light.