Pamela Allara, Ph.D., my colleague in art history and all things, contributed this post about a stunning exhibition in Boston.

Firelei Báez’s installation, “To Breathe Full and Free: a declaration, a re-visioning, a correction…” at the Institute of Contemporary Art’s Watershed gallery was one of the most exciting exhibitions that the ICA has mounted in the three years since it opened at this location.

The artist at work on her monumental installation

It is certainly the most memorable.

Firelei Báez was born in the Dominican Republic in 1981. Baez’s mother is Dominican and her father Haitian. Because the Dominican Republic was settled by the Spanish, and Haiti by the French, there has always been tension between the two countries. It is this unsettled history that Baez brings to the surface in her installation.

In the main exhibit space, a monumental series of arches rise up from the marina where the Watershed is located.

Firelei Báez, To breathe full and free: a declaration, a re-visioning, a correction (19°36’16.9″N 72°13’07.0″W, 42° 21’48.762″ N 71°1’59.628″ W), 2021.

Firelei Báez, To breathe full and free: a declaration, a re-visioning, a correction (19°36’16.9″N 72°13’07.0″W, 42° 21’48.762″ N 71°1’59.628″ W), 2021.

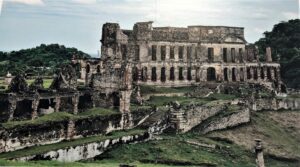

From the color photograph at the exhibit’s entrance we learn that the installation references the ruins of the Sans-Souci palace in Haiti. Sans-Souci was built by Henri Christophe, a former slave. He became a revolutionary general who crowned himself king. He is part of the heroic history of Haiti as the site of the first successful revolt by slaves against a colonial power in this case France.

The palace itself was destroyed by an earthquake in 1843, its ruins a potent symbol of the region’s turbulent history.

Sans-Souci Palace, 1813. Haiti

The artist created a smaller version of Sans Souci on the Highline in 2019

Báez further layers that history with Boston’s own. As one approaches the Watershed space along Marginal Street in East Boston, one passes the decaying former docks on the harbor where for two centuries Boston entrepreneurs actively traded goods, including until the early 19th century, human goods.

As generally told, Boston’s history is a triumphant one, emphasizing the shedding off of oppressive British rule, but Baez reminds us that history is often more complex, and more morally conflicted.

Ironically, Báez was told when she was growing up that as a Dominican, she had no history. The installation makes clear that we all carry histories with us, and it is important to acknowledge and reflect upon them.

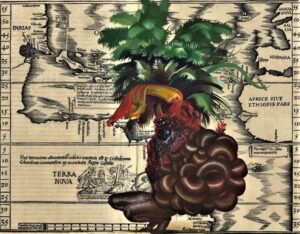

On the entry wall, has painted a large, impressive mural. On the upper left is an inset reproducing a 19th century map of “Boston Harbor and ‘The Sea of New England.’” – the artists fascination with maps has appeared in other works as here

The waters of the harbor, occupying the majority of the mural’s space, are appropriately turbulent, and on inspection one finds that immersed in the waters is a map of Boston and Cape Cod. It also includes the barnacles so common in the nearby waters.

Below the map, Báez has painted a large bouquet of marine flora, ferns and feathers, all native to the Caribbean.

She has stated that the bouquet also contains a mythological figure from Dominican folklore, Ciguapa; perhaps those are his wings we see at the top of the image. Where one would normally find texts and images provided by the curator, here we have a seascape whose history we must attempt to navigate before entering the main space.

Once, there, we leave Boston and its maritime history behind, and are plunged into a different space altogether. As if rising from the ocean floor itself, a monumental ruin punctuated with arched openings she constructed in the space from foam, plywood and plaster tilts across the space. A pierced blue fabric draped from the ceiling provides the illusion that we are perhaps underwater. The sense is both unsettling and exhilarating. One is drawn to walk through and around the arches in order to get a feeling for the palace it references.

But as with all ruins, much is left to the imagination. We must reconstruct this history on our own. The blue references the ocean, to be sure, but also, according to the artist, the valuable indigo dye used by the Yoruba in Nigeria for their cloth, which brought them wealth through its trade.

The history of this trade is explored in the accompanying installation by Boston artist Stephen Hamilton. The images Baez has screened onto the structure initially hold some clues, but why a lion and a panther, neither native to the Caribbean, obviously, and what do the abstract symbols refer to?

This civilization remains obscure and remote, and what’s left of its history, as indicated by the barnacles that ring the bottom of each arch, is decaying. But before the arches sink back into the (ocean) floor, we are drawn to repeatedly walk in and around them as if they might reveal the cause of the structure’s demise. Of course, as we walk, it is impossible not to ponder the decline of all past civilizations and the inescapable fact that our own seems to be on the same trajectory.

Even though this is a created ruin, I found it as compelling as visiting actual ruins. Why do we go to Knossos or to Chichen Itza? For me, and I suspect for most visitors, they bear witness to human creativity, which endures even as civilizations decline. Thus, the monumental architecture is a metaphor for human achievement in general. And finally, the works, even in their ruined state, are beautiful, and in their beauty, remain inspiring.

Photo Credits

Artist Portrait Antoine Boontz

Artist at work, and Untitled Terra Nova: Amani Willett for The New York Times

Installation view, ICA Watershed, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photo by Chuck Choi. © Firelei Báez

Close Up of Sans Souci arches Jesse Costa/WBUR

Mural details and Sans Souci on the Highline Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan, New York. Photo by Chuck Choi. © Firelei Báez

Barnacles Pam Allara